A perfect crime cannot end in a trial. In this one, the main suspects have presented alibis, which history will judge. Vladimir Putin, then Prime Minister of Russia, was attending the opening ceremony of the Beijing Olympic Games on August 8, 2008, when bombs and artillery fire set the skies of South Ossetia ablaze. A few days before entering the war, Mikhael Saakashvili, then President of Georgia, was in Italy undergoing slimming treatment. Is one preparing for war by writing a speech calling for "impartial arbitration" of the Olympics, or by reducing one's weight in a discreet clinic? And what can we expect from the International Criminal Court (ICC), almost thirteen years after the events with regard to this five-day conflict that has turned European geopolitics upside down?

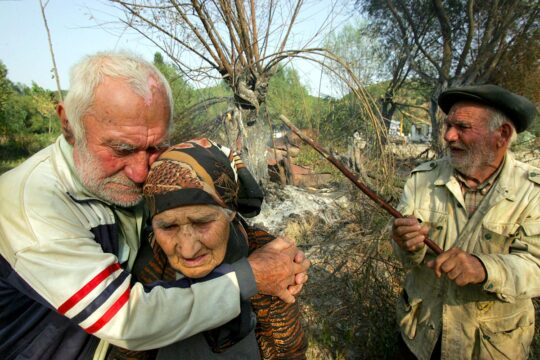

Gaiozi Babutsidze, 82, did not have time to ask himself these questions. On August 8, 2008, he and his wife were trying to save their cattle from being blown up by bombs. His village, Achabeti -- six kilometres north of South Ossetia’s capital Tskhinvali on the road to the Roki tunnel from which columns of Russian tanks were emerging -- was in the firing line. A Volga braked in front of their house, and Ossetian militiamen descended from it. "This is no longer your home!" they shouted. "My wife screamed, they beat me, I fainted, then they sprayed me with water and took us away," he recalls.

Babutsidze, 70 years old at the time, had been working as a fireman in Tskhinvali for 18 years. "They showed me about 20 killed soldiers, Ossetians and Georgians. They forced me to bury them with my bare hands. I was covered with their blood. Then they brought bags, and it went on. One day, there were 50 bodies. Another day, we were near the cheese market when an Ossetian militiaman, a big strong man, said that we Georgians should be killed. He led us to a pit. But there, two Jeeps arrived, driven by Russians in civilian clothes. They told the militiamen to stop." Babutsidze and his family were later taken by the Red Cross and evacuated to Tbilisi, the capital of Georgia. The man spent 19 days in captivity, he said, burying bodies and cleaning up rubble.

Controlled “ethnic cleansing”

The war lasted five days, but the Russian occupation lasted several months and South Ossetia ended up separated from Georgia. A total of 850 people lost their lives, including 228 Georgian civilians, according to an independent fact-finding mission of the Council of Europe. The South Ossetians, for their part, declared 365 victims, "a figure that probably includes both military and civilians”. There were 162 Ossetian civilian victims according to Moscow, which at the beginning of the war denounced a “genocide” of the Ossetians. Babutsidze is one of the 30,000 internally displaced Georgians who fled the separatist republic, never to return. The old man lives on 45 laris per month (about 12 euros) in the camp of Shavshvebi, in the centre of Georgia. He expects nothing from the ICC, he confides to us, but hopes to "get something from the Strasbourg Court", the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR).

On 21 January 2021, in a decision described as “historic” by Tbilisi, the ECHR condemned Moscow for a series of violations, including the “inability of Georgian nationals to return to their respective homes” in South Ossetia. A second decision is awaited regarding the victims' demands for compensation, including that of Babutsidze. This is an acknowledgement of the "ethnic cleansing" of Georgian citizens carried out under the effective control of Russia, says Tina Burjaliani. This jurist, former Deputy Minister of Justice of Georgia (2007-2012), waged a counter-attack during the conflict at the ECHR, the International Court of Justice (ICJ) and the ICC. The Court in Strasbourg has just outpaced the Court in The Hague, with a decision that marks new ground in international law.

“When the war started, I was actually in The Hague, not for official business but completing my studies at the Academy of International Law,” recounts Burjaliani. “I immediately received calls from the Minister of Justice and others in the government to explore legal remedies available for us. We filed a request for preliminary measures at the European Court of Human Rights and International Court of Justice. During that time, I met the Prosecutor of the International Criminal Court. Georgia has been a state party to the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court. The Prosecutor's office was interested in the situation. It was an international armed conflict in the territory of a state party, they were interested in getting information. I provided them with what was available at that time.”

Tbilissi and Moscow bombard ICC with information

On August 14, 2008, Luis Moreno Ocampo, then Prosecutor of the ICC, opened a preliminary examination. This led to an investigation only eight long years later. During this time, in Georgia and Russia, investigations were quickly opened, submerging the ICC. On the Georgian side, “the information included the reports received at the hotlines that different government institutions had at the time,” says Burjaliani. “The National Security Council had one, and the Ministry of Conflict Resolution also had another, and they received calls from the victims of this conflict, civilians just describing the ongoing violence.” Then Georgia’s prosecutor general opened an investigation. Burjaliani says this became a major source for the Ministry of Justice to provide information to the ICC.

Still according to Burjaliani: “Russians managed to collect and file about 3,500 individual complaints against Georgia at the European Court of Human Rights. We learned later that these complaints were also communicated to the ICC Prosecutor's office to show that violations of human rights occurred against ethnic Ossetians by Georgian forces.” In her letter requesting the opening of an investigation, the ICC Prosecutor indicates that “the Russian Federation, in the course of its investigation between 2010 and 2014, considered 575 allegations made by Georgian victims against Russian servicemen. These allegations referred to murder or attempted murder, destruction of property and pillaging.” In a letter of 18 June to the ICC, the Russian authorities sent their conclusions. They said that after questioning 2,000 Russian soldiers and examining documents provided by 50 units, “the investigation has established that the command of the Armed Forces ... had taken exhaustive measures to prevent pillage, violence, indiscriminate use of force against civilians during the entire period of the Russian military contingent’s presence in the territory of Georgia and South Ossetia.”

RUSSO-GEORGIAN WAR (2008)

A "punitive expedition"...

On the political level, the loss was sharp for a Saakashvili already criticized by part of his population. In 2003, during the Rose Revolution, the Georgians brought him to the presidency at the age of 36, overthrowing Russia’s man Eduard Shevardnadze. Saakashvili reformed Georgia and turned the country towards the West. His opponents, including current President Salome Zurabishvili, accused him of having provoked Russia and, by ordering the first bombings on the night of 7-8 August 2008, triggered the "Russian punitive expedition". Saakashvili defends himself against this, swearing that he has "all the evidence of bombing of villages in South Ossetia [and] that Georgia attacked only after Russian tanks had entered the territory of Georgia without authorization". This was an "aggression" according to Tbilissi, a "peace enforcement operation" according to Moscow. Europe got involved, and on 12 August, Nicolas Sarkozy of France, as President of the European Council, visited Moscow and Tbilissi. A ceasefire plan was agreed, which led to the cessation of fighting and later to the Russian withdrawal to the territory of South Ossetia.

Once the smoke of the war had dissipated, Saakashvili did his accounts: he had to rehouse around 30,000 people and 20% of his territory was beyond his control, if we add to this the loss of Abkhazia in 1992. His slimming, then, was rather of his country, and Putin had given the Caucasian an implacable "Russian lesson", as described in a documentary by exiled director Andrei Nekrasov.

… or a “home-made recipe”?

But without revisiting 2008, one cannot understand what happened. “The Russian lesson wasn't just for bad pupil Saakashvili, far from it," explains Thornike Gordadze, an academic and former Georgian deputy foreign minister in charge of European affairs. "This was the year when Kosovo became independent and Georgia became close to NATO. In February, the Russian reaction [to Kosovo's declaration of independence] was very bad, even more violent than that of Serbia.”

Three days before Kosovo’s declaration of independence supported by Brussels and Washington, a Putin on the rise gave a press conference lasting four hours and 40 minutes - available online on the Russian presidency website. Kosovo? "It is a signal for us, we will react to the behaviour of our partners in order to safeguard our interests,” declared Putin. “If they feel they have the right to defend their interests in this way, why not us? We are not going to be fooled or necessarily act in a direct way. We have a home-made recipe, and we know what we are going to do.”

"Homemade recipe". These two words immediately resonated in Georgia, where demands for independence "prepared" in Moscow were simmering in Abkhazia and South Ossetia, says Gordadze. A week later, Saakashvili went to Moscow to discuss "the lifting of the Russian economic embargo, the Kosovo situation, the peaceful settlement of conflicts on Georgian territory and the restoration of air communication,” says Gordadze. “When Putin demanded that he renounce joining NATO, Saakashvili was more convinced than ever that it was necessary to join. Putin made the Georgians understand it was coming to them." In particular, Putin reportedly said to Saakashvili: “You think that things are going badly, I think things are going well and that they could go worse." A few days later, on March 21, the Duma, the lower house of the Russian parliament, voted to recognize the independence of South Ossetia and Abkhazia.

Amber light

Tension rose. At the beginning of April 2008 in Bucharest, the NATO summit was due to examine the candidacies of Ukraine and Georgia. Washington was in favour; Germany and France wanted to spare Russian susceptibility. Putin was in Bucharest, lobbied, and obtained a final declaration promising "that these countries would become members of NATO" but postponed accession. “That's the climax," says Gordadze. “The ‘no’ side congratulated itself by saying 'we have saved peace'. But Russia had a de facto veto over the enlargement of the Alliance. The Russians saw this as an amber light. In their minds it meant: ‘The Europeans consider that this is our zone of influence, we must consolidate this state of affairs. It means that enlargement will never happen’."

A week after Bucharest, Putin issued a decree instructing his administration to establish direct, official and legal links with the secessionist authorities in Abkhazia and South Ossetia. Armed incidents increased, as described by Amnesty International in its report "Civilians in the line of Fire”. The signals of war were further amplified in July, when the Russian army organized a large-scale military exercise, “Caucasus 2008”, involving 8,000 soldiers and 700 armoured vehicles, on the Roki and Mamisoni passes on the Russian-Georgian border of Ossetia. The "fictitious" enemy of the exercise was… Georgian. According to Tbilissi, the Russian units did not, in reality, return to their bases. At the same time, Georgian-American exercises called "Immediate Response" were taking place in Georgia, involving 1,650 soldiers, including no less than a thousand American officers.

But these were just exercises. The ICC’s preliminary examination was launched one week after the war. "August Ruins", a comprehensive report of events written by Georgian civil society, was quickly forwarded to Prosecutor Ocampo, along with numerous other investigative reports - including that of the Council of Europe - documenting serious crimes including forced displacement of the Georgian population that may constitute a war crime. There is no shortage of factual and legal material. Proceedings have been opened in Georgia. But for nearly eight years, the ICC has simply continued to "observe the situation".