It did not take long for the keys to Gibril Massaquoi's trial to be laid before the judges. Since 23 February the Finnish court, relocated for several weeks to the Liberian capital, has heard the first eleven prosecution witnesses (including one behind closed doors) testify against the former commander and spokesman of the Sierra Leonean Revolutionary United Front (RUF) rebel group. And these hearings quickly illustrated the strategies of both the prosecution and defence.

The penal stakes of this case were, in fact, drawn up as soon as the case emerged in March 2020, when Massaquoi was arrested in Finland. Massaquoi had been granted a residence permit thanks to his collaboration in the 2000s with the prosecutor's office of the Special Court for Sierra Leone, a UN-backed court that was active between 2002 and 2013. Based on information provided by the Swiss NGO Civitas Maxima and its Liberian partner the Global Justice and Research Project and after a year and a half of investigation by the Finnish police in Liberia, Massaquoi found himself prosecuted for war crimes and crimes against humanity he allegedly perpetrated on Liberian soil between 1999 and 2003.

The bulk of the charges are, at least initially, related to acts allegedly committed between 2001 and 2003. However, this period was marked by the end of the war in Sierra Leone, the defeat and disintegration of the RUF, and the rallying of almost all its leaders to the national disarmament and reintegration process under the aegis of the UN. Why would Massaquoi have continued to get his hands dirty in Liberia when he could extricate himself from ten years of war by being forgotten in Sierra Leone? "From the point of view of probability, it doesn't make sense to me," said Lansana Gberie, a respected scholar and expert on the Sierra Leonean civil war, who often met Massaquoi during this period. "In 2001-2002, he was looking for a way out. I don't think a guy like him would be stupid enough to go back to Liberia. But maybe, who knows? Some of the RUF guys went to Liberia, several of them. He may have been one of them. I'd like to see what they found," the expert, now a diplomat, said in an interview with Justice Info in April 2020.

Frugal court keeps low profile

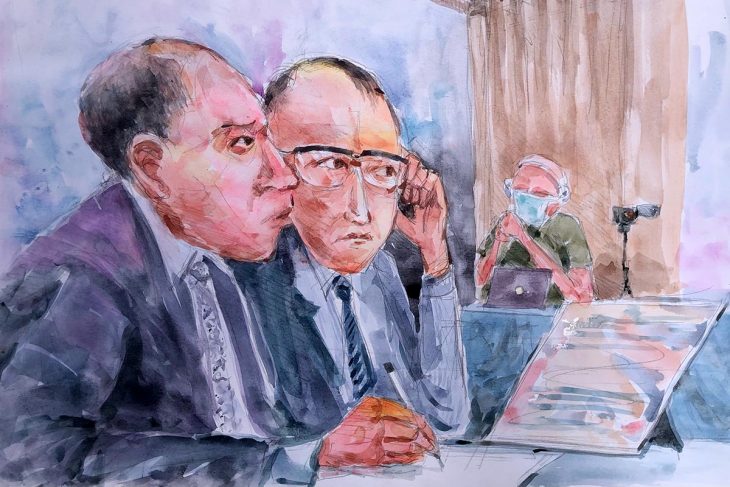

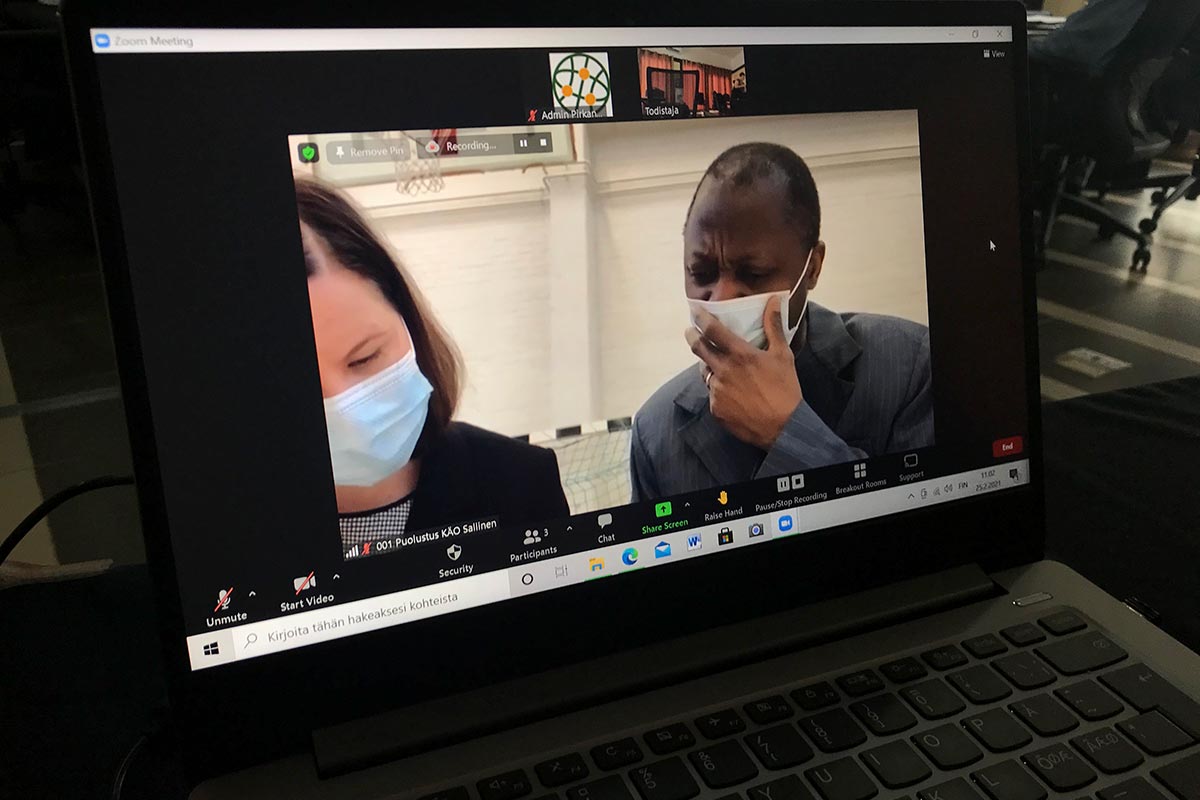

In Monrovia, the trial is being held in a place that the Finnish court prefers not to make public. The layout of the courtroom meets only basic needs. No decorum, a staff reduced to the size of a commando. The four judges - two women and two men - face the witness and two interpreters, one Liberian and one Finnish. Everyone sits at the same height, in front of trestle tables covered with neutral, blue-black cloth. To the left of the judges sits the defence lawyer; to their right, the two prosecutors. A video link connects them to the accused and his second lawyer, who have remained in Finland. From Finland, they can see the witness, but not the other way around. Behind the interpreters, three or four seats are reserved for the few accredited journalists, a respected Liberian cartoonist invited to do some sketches, an NGO observer, and another one from the former Special Court for Sierra Leone.

A small adjacent room, equipped with a large screen, hosts a handful of other Liberian reporters and observers who monitor the hearings. For reasons of security or discretion, no members of the general public are present. There are no radio or television broadcasts of the trial. With the exception of one victim of sexual violence who testified in closed session, the faces and names of witnesses are known to those present, but the press was warned not to disclose their identities. (Code names of the Finnish police are used here).

Summary executions and sexual violence in Waterside

The first ten witnesses who testified publicly recounted serious violence near the Old Bridge in the centre of the Liberian capital at the end of the second and last civil war (1999-2003) some 20 years ago. They describe their arrival in this shopping district of Waterside, where all the stores but one, selling biscuits, were closed. Most of them depict times of acute shortages and high armed tension. “At that time there was no food,” explains ‘Civilian 46’, and “the war was in Monrovia”. All these civilians were either in search of food or were regulars who sold small goods in Waterside.

Looking directly at the person she is addressing, ‘Civilian 75’ recounts clearly and without hesitation the incident they are all telling. “All stores were closed. Only one was open. We saw people pouring in, taking goods. The store was looted. After that we saw people with guns. They started shooting at people. They took us and tied us, hands in the back. They beat us up and carried us to their checkpoint. They tied [‘Civilian 65’] and I together and told us to look at the sun. That’s when one of them called Angel Gabriel said that we are the enemies and that we came to spy. He got us six by six in line and started to kill.” With the people killed inside or in front of the biscuits shop and those executed near or under the bridge where they had been taken, “many people died in the process”.

According to all witnesses, one man stands out as commander of the group of these armed combatants. They say it was he who gave the order to kill or killed himself in cold blood, or committed sexual violence. Witnesses identified this man as "Angel Gabriel" - the alleged nickname of Gibril Massaquoi, who refutes it - or "Angel Massaquoi" or "Angel Gabriel Massaquoi", or even "Angel" for short. Many say they recall that he had a Sierra Leonean accent. “While walking towards the group, he introduced himself as the commander. He said ‘I am Angel Gabriel Massaquoi. I am the one who can send you to God and you tell him that I have sent you’,” recounts ‘Civilian 07’, a strong, expressive woman who sometimes seems to regard the theatre around her with an amused air.

The importance of a date

The first three witnesses told Finnish police investigators in 2019 that this bloody incident took place in 2003. They now say in court it was in 2000. A fourth witness, who also placed the event in 2003, now places it in 2001. The others place it in 2001 or 2002. Almost all, however, describe a state of war in the centre of the capital. Most of the witnesses evoke, at the time of the events, a period of great armed tension in Monrovia, intense noise of machine-gun fire and fighting.

For the defence, these elements are decisive. It intends to demonstrate that such a description can only correspond to the period of June-August 2003, when LURD rebel forces attacked the Liberian capital in waves to force President Charles Taylor out of power. It is this period that Liberians have called the first, second and third "world war" - "world war one", "world war two" and "world war three". For a few months, as the peace talks in Ghana stalled, rebel forces launched offensives on the capital and subjected it to intense bombardment before withdrawing or momentarily ceasing fire. There were three waves of assaults, three "world wars", the last of which brought the defeat of Taylor, who went into exile in Nigeria and was later handed over to the Special Court for Sierra Leone which sentenced him to 50 years in jail.

But almost 20 years after the events, popular confusion about what precisely these three "world wars" refer to is common. Several witnesses, confronted by the defence with their changing testimony, said in court that the three "world wars" corresponded respectively to the years 2001, 2002, and 2003. Some made these and the second civil war in general one and the same thing. And the Finnish actors in this trial have, of course, no personal knowledge of these events.

If the defence establishes that the incident could only have taken place during this period in 2003, it can brandish its alibi, saying that at that time Massaquoi was officially the number one informant for the UN prosecutor of the Sierra Leone court and was living in a protected residence in Freetown. And if the witnesses use the years 2000, 2001 or 2002 as a basis for establishing the facts, the defence intends to show that there was no such fighting in Monrovia at that time.

Incoherence or overall probative value?

“If one witness changes the story, OK. But three or four? It’s not possible anymore,” confides defence lawyer Kaarle Gummerus outside the courtroom. The defence suspects, at a minimum, that the witnesses consulted among themselves or at worst that they were told to give a name and date.

Gummerus has some physical resemblance to Jacques Vergès, the most famous of French court slayers. With his mischievous eye, thin lips and sometimes caustic attitude, he systematically points out the inconsistencies in the testimonies that will support his line of defence. But the Finnish style does not go in for humiliating witnesses. For those accustomed to the aggressive cross-examinations of British or American lawyers, the Finnish judicial joust appears excessively delicate.

The strategy of Massaquoi’s lawyer is a combination of alibi (my client was not there), denial (my client never had the nom de guerre "Ange Gabriel") and suspicion about the integrity of the investigation.

The prosecutor, for his part, is counting on the mass effect of human testimony, the only available incriminating evidence, and on a certain leniency for the contradictions, inaccuracies and revisions noted at the hearings. "We have to take all the testimonies and see if similarities overcome inconsistencies," explains Tom Laitinen on the sidelines.

At the end of the first two weeks of hearings in this part of the trial, which deals with the crimes committed in Monrovia, the defence attorney seemed more serene.