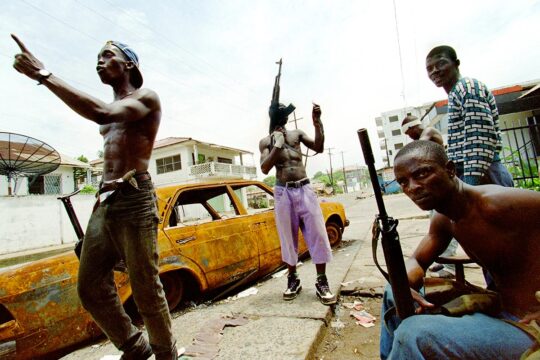

On Saturday March 20 in Monrovia, the main Liberian actors advocating for a national war crimes court to try crimes committed during the civil wars of 1989-2003 were meeting in a big hotel in the Liberian capital. The most activist and well-informed community on this issue were there to assess the impasse in which their project finds itself and to reflect on their strategy. They included former commissioners of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC), members of parliament, traditional chiefs, NGO activists, victims' representatives, and foreign diplomats.

At the same time, the trial of Gibril Massaquoi had been ongoing for a month on the outskirts of the city, before a Finnish court relocated to Liberia for the occasion. This was the first trial to be held in the country for war crimes committed on Liberian soil some 20 years ago. It was an event. Yet most of those present at the conference had no idea about it. Of the three former TRC members, two knew nothing about the ongoing trial; the third, a former journalist, had read the few press reports but had never been there. The number two at the embassy in Sierra Leone, Massaquoi's home country, didn’t know that the hearings were being held a few miles away and was unaware that the trial would soon continue in Freetown, the Sierra Leonean capital. Larry Younquoi, the MP who has been leading the campaign for years for a national court to try former Liberian warlords, knew no better. "That’s not the enthusiasm expected. There is not much publicity. We don’t know where the [hearings] are being held. The momentum has not been built," he confided during a coffee break.

“They have to make concessions with warlords”

When news circulated at the end of January that the Finnish judiciary would be coming to Liberia to hold the bulk of the Massaquoi trial hearings, the same civil society and some international NGOs hoped that the event would create a new political and judicial dynamic in the country, promoting the domestic prosecutions for which they have been campaigning for almost 20 years. There was talk of a live broadcast of the trial, a new momentum for a public debate. None of this happened. The Finnish court did its job, it visited the sites of the alleged massacres, it listened to 55 witnesses during 21 days of hearings spread over six weeks. But it did so discreetly, in an undisclosed location, without a public gallery and in the presence of only a handful of strictly accredited observers and journalists.

The first factor explaining this disillusionment is political. Trying former warlords in Liberia remains a very sensitive issue. It soon became clear that the Liberian government, while allowing the Finns to conduct their hearings in Liberia, did not want to risk the event making too much noise.

"Liberia is a tricky terrain," says Hassan Bility, director of the Global Justice Research Project, the Liberian NGO whose work has led to most of the prosecutions of Liberian suspects who have taken refuge in the West. "From 1985 to now, nobody has won a presidential election without winning Nimba county," whose main representative in the Senate is Prince Johnson, a notorious player in Liberia's first civil war who became famous for filming himself ordering the torture and execution of former dictator Samuel Doe in September 1990. "Nobody wants to offend Prince Johnson. Politicians think that if he gives you his support, you win. This is a challenge," the activist explained. And it is also a challenge for Liberia's current president, former football star George Weah, who had to make alliances with political forces involved in the civil wars of 1989-1996 and 1999-2003.

As soon as leaders come to power, says Younquoi, "they have to make concessions with warlords. As it stands, it is very difficult to achieve [war crimes accountability]. Do we have people with enough spine to do it? No." This explains, in his view, the frustration and anger of young Benjamin Myers, now chief of staff to a member of parliament. At the conference, he pointed the finger at all levels of civil and political society. "It makes no sense that after 17 years we are [still] talking about war crimes justice," he asserted, denouncing former warlords and naming the most famous: Prince Johnson, Alhaji Kromah, George Boley, Sekou Konneh. "They postulate with arrogance. They are not being remorseful. They are continuously reminding us what they did."

“Liberia only provides a forum”

In such a context, the Liberian government and Finnish judiciary were walking on eggshells. And both sides agreed to compromise, remaining vague about the agreement between them, pretending that it was not a trial but "collecting evidence", and being as discreet as possible about the hearings held in Monrovia.

Since the beginning of the investigations in the Massaquoi case, everyone has settled for a minimal relationship. The Finnish police have not investigated with the support of their Liberian counterparts, as is traditionally done in the context of mutual legal assistance. When the court visited the scene of the alleged crimes in mid-February, it was not accompanied by an escort. No Liberian security services were engaged to protect the trial site. Liberian authorities made sure to minimize the importance of the event, while the Finns were satisfied with such complete autonomy and low profile.

Sayma-Syrenius Cephus is Liberia's Sollicitor General. In an interview in Monrovia, he said that from the outset it was he who authorized the Finns to come. “They had a list of witnesses they talked to. They wanted to transport them to Finland but because of the pandemic they were not able to,” he explained. “So they decided to come to Liberia along with the defence, the prosecution and the judges to hear the witnesses’ testimonies. It’s not a war crimes court, it’s not a formal deposition. We’re not considering this as a hearing. What makes it different [than a trial] is that they simply come to hear witnesses but the trial is in Finland, it is not in Liberia. We call it a constructed trial. Liberia, to a large extent, only provides the forum but the whole process is in Finland.”

When asked about the risk of the government being suspected of promoting, through the Massaquoi trial, the idea of a national war crimes tribunal, he responded clearly: "As we stand, the position of the government of Liberia is that first, we are looking at total stability, providing basic social services, building roads. The question is: do you, at this time, abandon building roads and schools and hospitals to go after suspected war criminals? Is that a major priority now? Are we going to spend significant time running after people on the basis of war crimes when we are supposed to be providing bread for those who survived? To me the answer, generally, is no. In my opinion we don’t need another court."

A venue kept secret

Other factors may explain the Liberian authorities' agreement to hold these hearings on their soil. The Massaquoi case is convenient for the government because the accused is not Liberian, is unlikely to disrupt the political game of former warlords, and is not known in Liberia. Some have also raised the fact that Massaquoi betrayed former Liberian president Charles Taylor by testifying against him before the former Special Court for Sierra Leone, a UN tribunal. It may have delighted some in Liberia to see him pay for his own alleged crimes. "I had no idea that it was Massaquoi who testified against Charles Taylor," exclaimed Sayma-Syrenius Cephus, before dismissing the claim. "Mr. Taylor left in 2003. The party detached itself from him 100%. Mr. Taylor is something of the past. He doesn’t have any supporter in Liberia. People don’t even know Massaquoi."

In the end, the result was a court set up in a small room in a luxury hotel, with between three and five seats inside the courtroom for journalists and observers, who agreed not to disclose the location of the trial. A small room adjoining the one occupied by the court could technically accommodate another 15 or so people, facing a pale image of the trial transmitted by a small camera on a large screen, with a poor, sometimes inaudible sound system. This room never hosted more than three hard-working young Liberians, recruited by a consortium of western NGOs to capture the verbatim proceedings and make them available to the rest of the world, and two Liberian journalists at a time supported by the NGO New Narratives, the only ones allowed to cover the event.

"We had planned a place that could accommodate 75 persons. We had originally planned to screen it in town for the public. That request was denied. I spoke to the Finnish head of investigations and they were concerned about security," says Bility.

Trial balloon

Beyond the political context, the Finnish ambition had never quite been to provide Liberians with a rendez-vous with justice and their history. Two Finnish interpreters, working in pairs with two Liberian interpreters, were recruited for the hearings in Monrovia, but their presence was strictly for the needs of the court. As this is a Finnish court, there is an obligation to record the proceedings in Finnish. And as soon as it was not the direct testimony from a witness in the local language, no English interpretation was provided. Journalists and foreign observers were left with a mixture of curiosity and frustration.

The president of the court often showed understanding for the dissatisfaction of the few independent observers present. But in the end, he stressed that this was a Finnish trial and that the first priority of his mandate was to hear the witnesses. Public interest was certainly desirable, but it was more of a luxury than a requirement.

Under these conditions, the Massaquoi trial could not create the expected judicial, social and political event. However, Hassan Bility wants to remain optimistic. "I think it is very helpful to Liberia and it’s giving hope to many people, it has created a national debate," he says. A western diplomat also sees it as a "trial balloon". "What you see here is a reflection of political balance. I would like to see it positively. It’s an incremental thing," he says. During its last two weeks of hearings in Monrovia, the court actually experienced a sudden surge of political interest. The ambassadors of the European Union and France went there, as well as the President of the Bar and, above all, the Minister of Justice, on 5 April, two days before the end of the hearings. The latter made no comment, but everyone was aware of the political significance of his brief visit.

Rendezvous in Freetown

From 28 April, the "Finnish model" will be tested in Freetown, the Sierra Leonean capital, in an extremely different environment. First of all, the accused is known to everyone in his country, whereas he was an unknown in Liberia. Media and public interest is likely to be much higher there. Above all, this trial does not create any political tension: in Sierra Leone, the warlords disappeared from the power structures immediately after the civil war in 2002. They have no political weight. There is no security risk, including for witnesses. The civil and legal successor to the rebellion of which Massaquoi was a member, the RUF Party, still exists but has never represented anything electorally.

Everything indicates, however, that the Finnish court wishes to conduct its hearings there with equal discretion. The Finnish ambition thus appears to be more of a practical method - a relocation to the crime site with maximum economy of means - rather than a model with a universal scope, prioritizing access to the greatest number and the educational value of a trial.