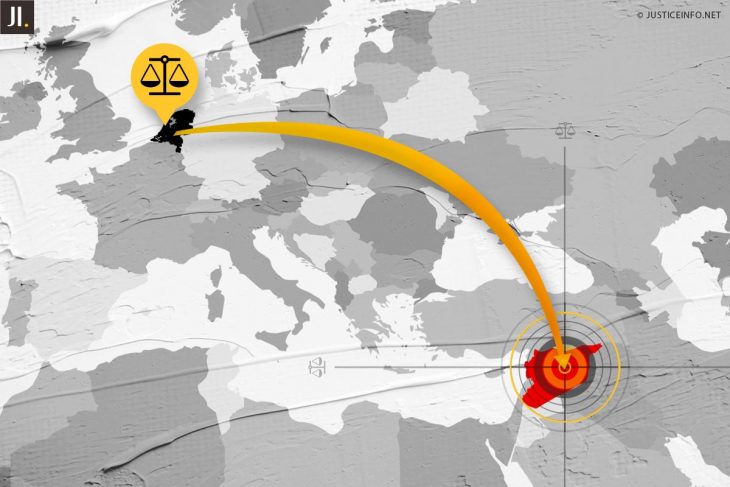

In an empty courtroom in Rotterdam this week, broadcast by skype, because of covid-19 restrictions, a single judge explained that Ahmad al Y. was formerly a commander with the Ahrar al-Sham militia in Syria. In 2016 he took refuge first in Germany and then the Netherlands. While in Germany, he had shown a fellow asylum seeker a video, which later set off the Dutch police investigation into his case in 2019. On 21 April, based on that evidence, Al Y. was found guilty of putting his foot on a dead government soldier, kicking a corpse, and calling those he defeated «dogs». The spread of the video via YouTube and other social media networks was detailed in the judgement. But because the faces of the corpses were not recognisable, his crime under international humanitarian law only earned him a two-year sentence, supplemented by an additional four years' imprisonment for membership of a terrorist organisation. The prosecution had asked for 10 years.

Al Y. was the first Syrian asylum seeker to be convicted in The Netherlands of war crimes. All the Syria trials so far have been of returning Dutch who joined either Jabhat al Nusra or Islamic State, two organizations considered as terrorist by The Netherlands. But the trend is upwards on the investigations into Syrian refugees who have been here for several years. Two more Syrians are currently being prosecuted in The Netherlands for international crimes. Abdelaziz A. was recognised by Syrian activists in the Amsterdam debate centre De Balie. He was charged with membership of Jabhat al-Nusra and complicity in murder. Abu Khuder, another commander of Jabhat al-Nusra, is accused of summary execution.

One-sided prosecutions

All the Syria cases so far are related to armed rebel groups. “The default is terrorism” when it comes to charging, says Cyril Rosman, who follows all the trials for the Dutch daily Algemeen Dagblad. Rosman says that it’s “only when there’s video or photo evidence that the prosecutors try with war crimes”. Like in all courts, dealing with social media evidence is relatively new for the Dutch, with considerable emphasis by prosecutors on the verification aspects to prove location and ownership. The terrorism charges however “don’t need a lot of evidence”, notes Rosman. And, he says, it’s been rare that proof emerged of what exactly people did while in Syria: “It almost never crops up”. War crimes charges “depend on the availability of the evidence”, agrees Christophe Paulussen, senior researcher at the Asser Institute in The Hague. When it does exist Dutch prosecutors “can go that one step further,” says Rosman.

Hope Rikkelman of the Syria Legal Network says there’s “a lot of frustration” among her Syrian colleagues from the fact that no one from the Syrian regime itself nor their accomplices have been arrested in The Netherlands. The pro-government militia were known as shabiha – ghosts – and researchers say many such ‘ghosts’ arrived among the ten of thousands of Syrians who fled to the Netherlands and applied for asylum. The special police unit for international crimes told Rosman that it is trying to find people on Syria’s president Assad side.

A list of obstacles

Many questions still arise though as to why such investigations have taken so long. The specialized police unit is small. They’ve taken some public criticisms over their (lack of) language skills and (lack of) relations with the community. Many asylum seekers don’t know they can make reports nor where to voice their suspicions. “The avenues are not clear at all”, says Rikkelman.

Syrian refugees are hesitant to make statements against alleged perpetrators, the Netherlands is a small country and “they fear not being taken seriously,” adds Rikkelman. And “people are very scared”, she says, that information will be sent to Syria and threaten their family’s safety. Some Syrians have also lost faith. “Expectations are low as opposed to a few years ago”, says Rikkelman, “[it’s] a long term relationship that we and the Public Prosecutors office and the Team Internationale Misdrijven [the police special unit] have to work on.”

Just finding out which trials are happening where, and attending the trials is also not always easy. It’s “not transparent at all”, says Rikkelman, “you have to either know via-via, or call the courts and simply ask if any cases are pending that week”. Interest among the Dutch audience in these war crimes trials is not high: “It happened far away, the people are not Dutch”.

As a result, the overall picture is patchy, even for those who follow the trials closely. Rikkelman describes all the challenges to prosecution as “a jigsaw where the pieces are not yet being put together” by Dutch investigators. “It’s all about context” she says; you need “the whole picture,” to understand the cases.

Why Syria is the new focus

The handful of international crimes cases tried and convicted in The Netherlands - some Afghans and Rwandans, one Congolese, one Ethiopian, a Dutch man who joined Islamic State and two Dutch businessmen connected war crimes in Iraq and Liberia - reflect how time-consuming and manpower intensive investigations can be. “In principle, the commitment to strive for accountability has been there for quite a while” says Christophe Paulussen, “but it’s difficult to pursue that goal if the conflict is still raging and investigators have difficulty in securing evidence”. Priorities like investigating the July 2014 shooting down of Malaysia Airlines aircraft MH-17 that affected many Dutch people may also seep resources.

Syria is now a focus for the Dutch, due to “a combination of factors”, says Paulussen. More access to the crime scenes, more actors such as the Geneva-based UN Independent International Investigative Mechanism – which the Dutch has supported strongly – have contributed. NGOs also provide expert input : a report from the Syria Center for Media and Freedom of Expression was quoted in this week’s judgement. A battery of specialists has also helped. The Netherlands Forensic Institute has been deployed to verify online sources on social media. Such evidence – as in the success of the latest judgment – “has been quite important in Syria cases”, says Paulussen. It seems that it’s only when the suspects trip themselves up that the Dutch have been able to compensate for investigators’ lack of access.