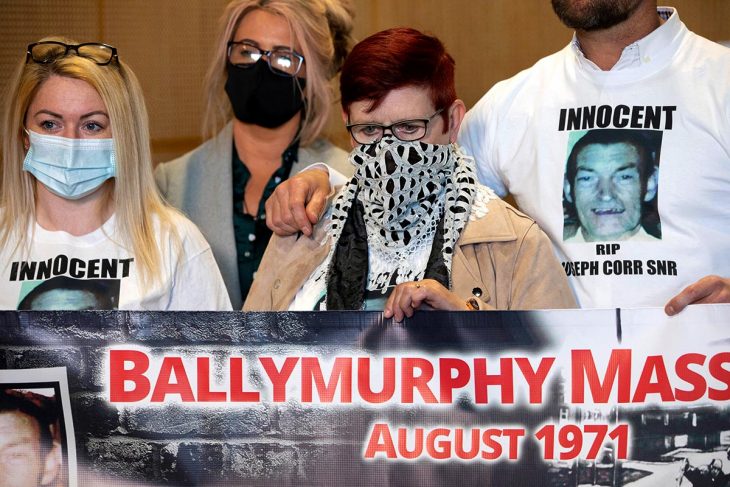

It required 100 days of evidence, more than 150 witnesses, including more than 60 former soldiers, more than 30 civilians and experts in ballistics, pathology and engineering. On 11 May this year, an inquest into events almost 50 years ago in Ballymurphy, a neighbourhood in western Belfast, Northern Ireland, found that ten people killed in the wake of a British Army operation were "entirely innocent."

The Ballymurphy inquest began in November 2018, examining the deaths that happened after a UK military operation aimed at arresting and interning suspected members of the Irish Republican Army (IRA) in August 1971. The victims included a priest who had been trying to help those wounded in the shootings, and a mother of eight. Nine of the 10 victims were killed by the Army, the coroner Mrs Justice Keegan said. She concluded, “that all of the deceased (…) were entirely innocent of any wrongdoing on the day in question" while noting that the deaths took place in a "highly charged and difficult environment" with widespread disorder, multiple explosions, shootings, incidents of rioting, arson and other civil disorder. Eileen McKeown, daughter of one of the victims, said her family was "delighted" with the findings and added that now the "world knows that they are innocent."

The inquest and its aftermath showed both that “those families have had to campaign for so long for something that was so evident to so many of us,” notes Lesley Veronica, lecturer in politics at Belfast Metropolitan College, and that the reactions across the community were again “polarised”. For example those close to the UK military thought “that's not true, this is another attack on our veterans”, Veronica says. She draws from her own discussions with family – she has a sister married to a former British soldier – and other members of the unionist-protestant community.

Would South Africa’s Truth Commission be a good model?

The Ballymurphy inquest is just one example of recent truth-seeking initiatives in Northern Ireland. But up until now, they have been a “patchwork”, says Brandon Hamber, The John Hume and Thomas P. O'Neill Chair in Peace at Ulster University, which “feeds into people's existing narratives.” These processes are “creating more differences, rather than if you were looking at issues more holistically,” says Hamber. “I wouldn't want to simply suggest those inquiries should stop because they have delivered for many families. But an agreed overarching process would be more managed,” he says.

What would a “more managed” process of truth-seeking look like in Northern Ireland’s fractured politics, where identity politics still loom large, where Brexit has stoked fears of a return to violence, and where devolved political structures are under deep strain? Is a call by former UK prime minister Tony Blair for a South-Africa styled “truth commission” on May 12 a useful way to approach Northern Ireland’s historical wrongs?

In fact, already, “there's a huge amount that's actually known about the reach and the extent of the conflict,” says Hamber. “Pretty much every individual killed, linked to the whole conflict, has been documented. The university has a database of all of the victims. We pretty much know in the majority, which organisation or when the state was responsible.” But he says, “there's no agreement on the causes” and that “makes the transitional justice process more difficult because you're sort of dealing with legacy issues within the context of an ongoing division.”

Double standards for victims’ compensation

Part of the patchwork approach have been ‘legacy’ institutions set up under a deal in 2015, to avoid political collapse in the province. The list of acronyms agreed is impressive: an “Historical Investigations Unit (HIU); and Independent Commission on Information Retrieval (ICIR); an independent Oral History Archive (OHA); and an Implementation and Reconciliation Group (IRG),” as reported to the UK Parliament select committee on Northern Ireland. But since the Good Friday Agreement in 1998 – an agreement between the British and Irish governments, and most of the political parties in Northern Ireland, on how Northern Ireland should be governed – political divisions have continued to stymie further agreement on the later envisaged ‘legacy’ institutions; they continue to engender debate and disagreement.

In March 2020, Northern Ireland’s victims’ and survivors’ (now former) commissioner Judith Thompson, reported back to politicians in Stormont – the seat of Northern Ireland’s parliament – on the continued lack of “effective institutions to be established to address their rights and their needs".

While some 3,720 conflicted-related deaths took place in the province between 1966 and 2006 and 40,000 people were injured, “213,000 people [are] experiencing a significant range of mental health issues which need to be addressed now", she said. "It is a societal issue and, if we do not deal with the past, it will continue to deal with us," she adds.

“I’d definitely say that we just repeat the same mistakes in Northern Ireland and that's been going on for 800 years,” says Luke Moffett, lecturer at Queen’s University Belfast where he specialises in reparations and victims’ rights. He’s been researching compensation offered to Northern Irish victims and notes “a massive diversity” between, for instance, someone killed 50 years ago, whose father was given 80 pounds for his daughter’s death, and a British soldier who was killed a few years later whose family gets over one hundred thousand. “The state [has been] buying off certain victims and excluding others. And that hasn't changed,” he says.

Different narratives of the past and lack of trust

Hamber brings his experience from South Africa, where a post-Apartheid Truth and Reconciliation Commission managed to draw a line, enabling that country to find a way forward. But in Northern Ireland, he says, “there's a fundamental lack of trust between the different political groups”. Where no one expects the other to tell the truth, such a model may not work. “You actually have to reach a certain level of cooperation and engagement if you're going to throw the doors of those most open to explore the truth.” In Northern Ireland, the causes of the conflict remains unsettled. “So you're trying to deal with the past in the midst of the facts underlying the most fundamental part of the conflict – where does this piece of land belong? – which is not really resolved.”

Moffett acknowledges that there is considerable resistance to truth-seeking, both from the state but also from a society “that wants to move on”. Just opening the archives, for example, would not be enough, he says. “Society itself needs to confront and know what happened in the past in order to stop it from happening again”. But whether that's a sort of information campaign or another process, it will be “very difficult”.

Lesley Veronica’s own father was killed by an IRA bomb. For her “the community that has the greatest difficulty taking responsibility is the unionist community,” because“the dominant narrative there is there was only a conflict because the IRA. And if that is what you believe, there wasn't a conflict, you don't need to take any responsibility. And then everything else sometimes becomes justified because of the IRA. And that is a real problem. And there is no looking in the mirror and being able to recognise this is what happened at our end, things that went wrong. And we need to hold our hands up about that.”

In a context where the exact root cause or causes of the violence are in fact “the fundamental area of disagreement” leading to “different narratives of the past”, says Hamber, “the idea of a truth commission, that's putting the cart before the horse.”