Just as it was planning to start a second case, after over twelve years of work, the Special Tribunal for Lebanon (STL) suddenly announced on June 2 that it is “facing an unprecedented financial crisis” and will have to shut at the end of July this year. Uncertainty surrounds what will happen to its people, work and archives. But after so many years and a billion dollars, it appears that this particular experiment in the international community’s efforts at accountability via courtroom has bitten the dust in ignominious fashion.

The shocking possible end of the STL is already attracting a variety of epitaphs. From Kevin Jon Heller, professor of International Law and Security at University of Copenhagen and Australian National University who says “we cannot be surprised, this is a tribunal that has literally accomplished almost nothing,” to the former head of STL outreach Olga Kavran describing the closure as “an absolute travesty of justice,” to defence counsel Natalie von Wistinghausen who says “we saw this disaster coming,” to the STL victims’ representative Nidal Jurdi for whom “this is a slap in the face of international justice.”

Jurdi believes “this will encourage more assassinations and attacks to happen because the element of deterrence will be destroyed” while Von Wistinghausen analyses that “priorities have shifted,” that efforts to investigate hot spots such as Myanmar and Syria are in vogue, and that “the political will is no longer there” among United Nations members to support the first ever international criminal tribunal to deal with terrorism.

So does this snap closure show that justice and accountability can be switched on and off as the international community’s fancy takes it? Or is the closure in fact an act of mercy, putting a failing institution out of its misery?

“Throwing the baby out with the bath water”

The rumours had been circulating for many months. A number of STL employees were let go last year. The tribunal now says that it can’t conclude the appeals proceeding in the one big case it was designed to address. This case, examining the car bomb that killed former Lebanese Prime Minister Rafik Hariri in 2005, saw three of the accused acquitted, and one Hezbollah member found guilty last year. It is currently on appeal. And on June 3 a Trial Chamber ordered the cancellation of the commencement of a second trial due to start on June 16, and suspended all decisions on pending motions. But “it would only take ten million to finish the second case,” claims Jurdi – maybe rather optimistically. He says the investigations are already done, and the bulk of the casework is already out of the way. “We only need maximum one year to finish it, if not less. We can do it fast.” But even that now seems impossible. “The STL was the only serious step to unflesh truth, and to establish accountability in Lebanon”, he argues, “if we destroy the STL now, what is left for the poor Lebanese victims: nothing. It’s as if you're throwing the baby out with the bath water.”

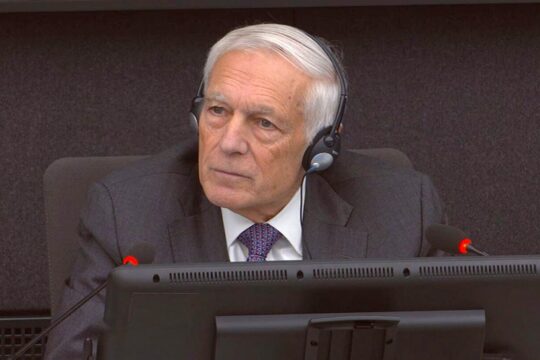

In filings, the STL registrar David Tolbert has outlined steps taken behind the scenes. Beirut was always responsible, and in recent years increasingly reluctant, to provide the 49% of the annual budget it owed. And Lebanon is now bankrupt. In December 2020, the United Nations appealed urgently for funds, and then itself stumped up 15.5 million US dollars to cover some 75% of the Lebanese shortfall. But the other 51% of the budget comes voluntarily from other states. “While certain donors have indicated their willingness to provide some funding” wrote Tolbert, “that funding alone would be completely inadequate to continue the Tribunal's work beyond 31 July 2021.” So he was forced this week to inform everyone. He had had “to initiate draw down activities related to the protection of witnesses and securing the Tribunal’s records, evidence and sensitive material” - known in common parlance as ‘pulling the plug’.

Insiders report that the STL Management Committee – comprising representatives of Lebanon, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom (Chair), Canada (Vice-Chair), France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the United States and the European Union – were increasingly unwilling to continue put funding into a court that takes far too long and costs too much money. “They’ve paid over the years; this year we haven’t seen much in the way of contributions from the management committee,” acknowledges Tolbert in an interview with Justice Info on June 3, without naming names. “It's a conscious, conscious decision,” one insider with knowledge of the management committee discussions says. Under Covid-budgetary pressures, taking 1.5 years to write a judgement and keeping staff on full pay all the while, may have tipped the balance against the tribunals’ continuance.

The STL’s uphill battle

Since the beginning of its activities, following four years of well-resourced international investigations, the STL has produced one judgement of some two thousand six hundred forty-one pages. It was “a mega, mega, mega case” argues Jurdi. Around 300 witnesses were heard in court and 170,000 pages of evidence introduced. That only one individual of mid-level responsibility was found guilty is due to the “very high” threshold for conviction in international criminal trials, says Kavran. She stresses that the judges made it very explicit and clear in their judgement that “this was not the work of one man”, but rather of a group. That message has not gotten through in Lebanon though, says Aya Majzoub who works on Lebanon for NGO Human Rights Watch: “People think, well, this took years and years and years, we spent so much money on this tribunal and at the end, it's convicted one member of Hezbollah and not the entire Hezbollah.” Kavran points out that the judgement gives details of the extensive criminal network needed to commit the attack. Heller, though, believes “a billion dollars is very expensive for what amounts to essentially a history lesson.”

The meagre result “really created this disillusionment with justice, both national justice and international justice. And it's just made people resigned to the fact that there will never be justice,” says Majzoub. “People had outsized expectations of what this court could accomplish, and it was used by supporters of Hariri and by opposition to Hariri, both for their own political ends, without really relying on facts. As time went on, it became just another political tool and the justice part of it, I think, got lost.” Kavran would have wanted people to hear that “all of Lebanon are the victims, because as the judges found in the judgement, this was not intended only to assassinate Hariri, it was intended to destabilise the country”. But explaining the STL “in a country that really has not much reason to have confidence in the international community was always going to be an uphill battle,” she notes.

The tribunal was just about to embark on a new case. Three car bombings, known as the ‘connected cases’ under the court’s statute, because they are alleged to have involved the same principals as the Hariri bombing. This new case was “building on lots of investigative steps that were already conducted by the first trial,” claims Jurdi. There was no need for further investigations, just litigation and “we had everything to move fast”. This new trial would have helped rather than hindered the court’s impact, says Kavran. “I would argue that the narrative will be very different if we're looking at one seemingly isolated assassination of a high-profile figure or if we're looking at a series of assassinations of high-profile figures.” The lack of funding is “a free gift for those who do not want accountability” in Lebanon Jurdi says.

Majzoub agrees that “what we find is that usually the [national] judiciary almost always shows bias in favour of the powerful interests in the country, whether religious, political or even financial interests.” There are strong citizens’ movements to counter impunity within Lebanon itself, she says, but “many people see the justice system in Lebanon as just an extension of the corrupt sectarian system that we have.”

Shutting down

It’s still a bit of a puzzle as to how exactly the tribunal actually be shut. David Tolbert says the statute provides for him to write to the UN Secretary General to inform him of the funding issue and that the closure will come via the Secretary General too. “There’s been a fair amount of planning,” he assures, although he stresses there would not be exactly the same kind of residual mechanism as have been established for the former UN tribunals for the former Yugoslavia, Rwanda, and Sierra Leone. And meanwhile they are still putting forward proposals in the hopes that funding may emerge. “But we have had no luck in getting a response” so far, Tolbert says, and so everything is “on hold”. Could the cases be revived, if mothballed? Von Wistinghausen believes that’s “unrealistic” although, technically, it may be possible. The hurt and anger is palpable from those who believed in this court’s mission. Tolbert says that of course his first concern is staff and people in Lebanon. But the lack of funding for the STL “will have an effect on the whole architecture of what we have been trying to do over the last thirty years…that’s the largest concern that haunts me,” he says. “What message does that send to victims around the world who are still waiting for justice? Because this tribunal doesn't exist in a vacuum or in isolation,” asks Kavran.

Beyond the rhetoric though Heller keeps circling back to the tribunal meagre achievements: “This is the tribunal that should never has existed,” he says. “We’ve spent a billion dollars on a tribunal which has convicted one person in absentia and whose only final convictions is that of a media company and a journalist [for contempt of court]. Is it really that shocking that the spigot might be turned off, even in the middle of proceedings?”