On May 27, the news broke. The Tk'emlups te Secwépemc Nation in British Columbia discovered evidence of unmarked graves at the site of a former residential school in the community. Geo-radar surveys, which capture images of the subsurface without digging, detected the presence of some 200 unidentified graves in Kamloops, western Canada, where many indigenous students attended school between 1890 and 1969. On June 23, there was another thunderbolt in Marieval, Saskatchewan, still in the west. This time, 751 graves were discovered by geo-radar near another residential school, located in the Coweness community.

Several other macabre discoveries have followed since, notably near Vancouver. There are now close to 1,300 of these forgotten graves, in close proximity to the settlements or religious communities supported by the governments of the day, which for decades tried to assimilate 150,000 young indigenous people. This uncovering of a long-hidden past has provoked an unprecedented wave of outrage across Canada. Suddenly, the citizens of this peaceful country have become aware of the violence suffered by several generations of indigenous people, who were uprooted from their families and their culture and had another language forced on them. Worse, the police often helped priests and religious communities take young children and send them hundreds of miles away from home. Thousands of victims of childhood diseases and abuse never saw their parents again.

A Truth Commission, then nothing

In 2015, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) heard testimony from those who lived in the residential schools across the country. Defeated, tearful, broken, these survivors told of the abuse they suffered, confided their fears. They explained how the system tried to "kill the indigenous in the child". The goal was to make these descendants of the forest and tundra peoples into Canadians like any other. The Commission's final report estimated that 3,125 children died in these institutions. Since then, the death toll has risen to 6,000 in 140 residential schools between 1880 and 1997. Six of the TRC's final recommendations concerned these missing children, so that their families would finally know the circumstances of their death and the place of their burial.

And since then? Nothing. No action plan to provide information on those children whose parents waited in vain at the train or bus stop at the end of the school year. No records sent to brothers, sisters, cousins and neighbours who lost a relative or friend. Emptiness and silence, as if this damning story had never happened.

Future excavations at the old Sept-Îles residential school

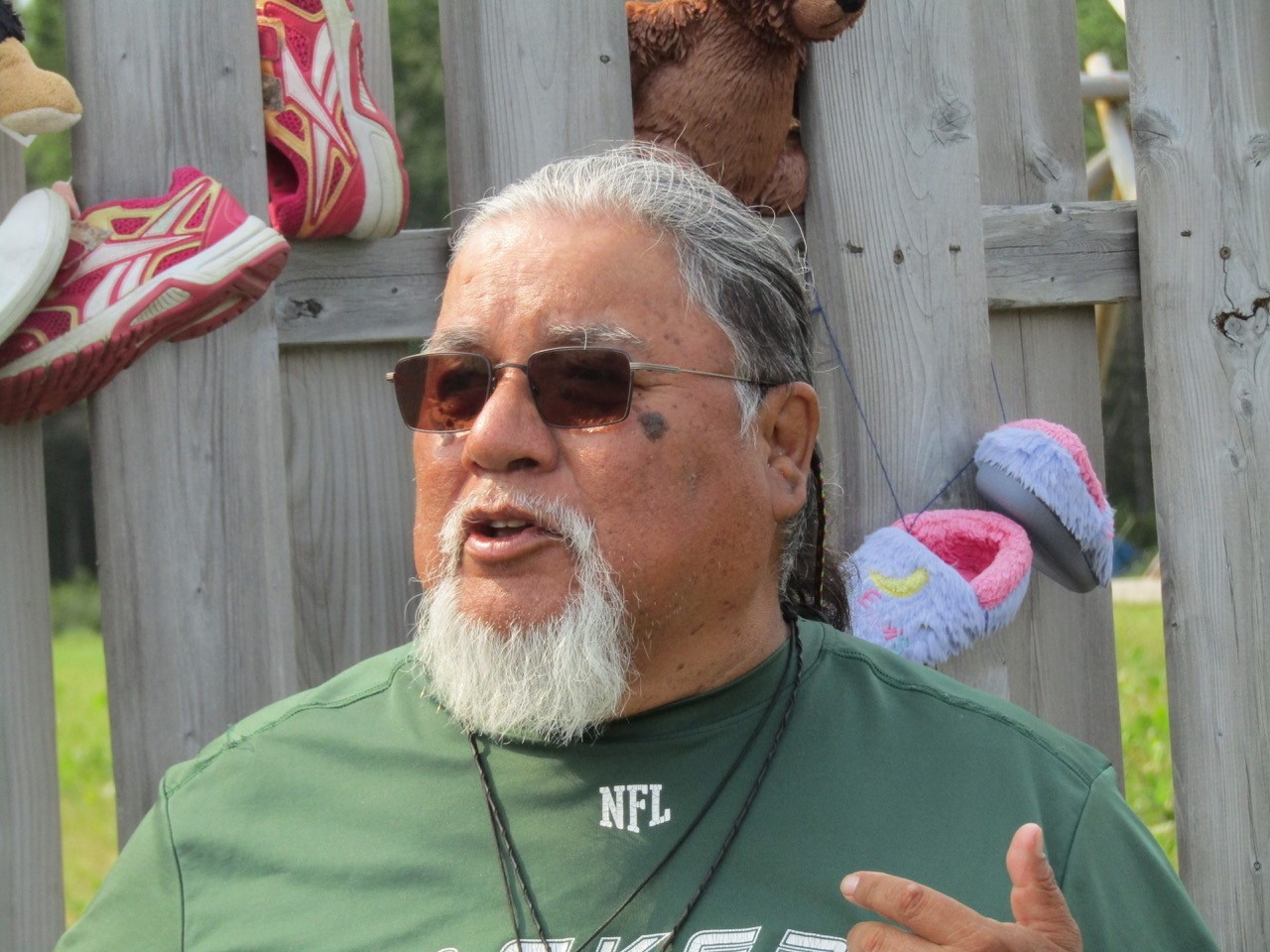

Yet when news of the unmarked graves discovery broke, Shan Dak Puana almost breathed a sigh of relief. "Finally we have proof of what has been said for years," exclaims this tireless indigenous rights activist, who lives in the Innu community of Uashat, near Sept-Îles, a port along the St. Lawrence River in Quebec. "Until now, governments didn't listen to us. Many non-indigenous people were in denial. I hope that now people will be empathetic and understand the huge social problems that stem from colonization and the residential school experience."

This difficulty in living, in combining a white identity imposed by forced schooling with one’s indigenous identity, Jean-Guy Pinette can talk about it for hours. When he arrived at the age of seven at the residential school near Sept-Îles, hundreds of kilometres from his home, he lost everything -- his language, his culture, his precious link with his grandparents. Fifty years later, he looks out over the grassy area of Mani-u Tenam, where the two buildings that housed young boys and girls taken from their families once stood. They all attended the school across the street, which has since become a clinic. "Even today, some of the former students feel bad when they enter this building," says the 60-year-old. "The smell, the place, reminds them of the trauma they experienced.”

The community's elected officials are considering demolishing the building to finally wipe out the past. This was the fate of a small building linked to the residential school in 2013. Gathered in a circle around the blackened ruins, the survivors cried, shouted, and told the rest of the village what they had experienced within these walls. Jean-Guy Pinette, a spiritual counsellor for youth, believes in the impact of this kind of event. Over the next few months, research using a geo-radar, such as the one used on sites in western Canada, is to be carried out on the grounds of the old establishment, not far from the beach. The aim is to determine if the graves containing the remains of children who died in the 1940s or 1950s are located there.

"This story must be known so we stop being victims”

"This may reopen wounds that still hurt," confides Jean-Guy Pinette. "We will be in pain. But we will also give ourselves love and strength. This will allow the former residents to explain to the younger ones what happened, to make them understand why their grandparents or parents who lived at the residential school use drugs or alcohol. We need to get this story out there so that we stop being victims."

A few kilometres from the site, Maricham Kapesh relies on traditional approaches such as healing circles to help members of her community face their inner demons. "We need to rebuild ourselves as a people," says this woman in her 70s who spent eight years of her life in the same residential school as Jean-Guy Pinette. "I was one of the first in my community to denounce the sexual assaults suffered at the residential school. They wanted to silence me because I was attacking the Church," she continues. "The discovery of the graves shows that the truth always comes out. People in Quebec, especially the young, need to hear our story from us. This will allow us one day to build ties and think about reconciliation."

Marie-Pierre Bousquet, director of the Native Studies programme at the University of Montreal, agrees. While directing a book on the history of residential schools in Quebec, it became clear to her that few people were listening to the voices of indigenous people. "Currently, everyone seems to be surprised by the discovery of these unidentified graves," says the anthropologist. "But several commission reports, written by experts, have long documented the disappearance of children. Have the politicians, like [Canadian Prime Minister] Justin Trudeau who cries in front of the cameras, read them?”

The Church targeted

Marie-Pierre Bousquet is pleased with the current surge of empathy towards indigenous people, which is leading citizens to come and meet with communities to share their pain. In an unprecedented event, many cities across Canada did not celebrate the national holiday on July 1, to instead reflect on how this nation was built. But Bousquet, who is familiar with the archives of religious congregations, also knows this may take time - a lot of time. "The geo-radar that is used on the former residential school sites does not provide high quality images of the ground," she explains. "Then you have to have archaeologists, bio-anthropologists, archivists working together. It's very resource-intensive. Not to mention that bodies degrade quickly in the ground after a few decades."

The Oblates, a religious congregation that ran a large number of residential schools across Canada for more than a century, are now committed to assisting in the search of their archives. But finding the boxes corresponding to the register of missing children in multiple institutions is not always an easy task, given that there was no concern for filing and the whereabouts of many archives are simply unknown. Since the discovery of the unmarked graves, the Church has been singled out for criticism. Many voices have been raised in Canada, including that of the Prime Minister, demanding an apology from the Pope. This demand was already included in the TRC's recommendations six years ago.

"I hope the federal government will not take advantage to absolve itself of its inaction towards the indigenous people," says Marie-Pierre Bousquet. Indeed, the forced schooling of children and dismantling of families were part of a plan by the Canadian authorities to assimilate the indigenous people. And the relationship of dependence in which these communities live still exists today, notably through the Indian Act, established in 1876, which governs their land rights.

In Quebec, the oppressed as oppressors

Jurist Fannie Lafontaine, who in 2019 participated in analysing the final report of the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls (MMIWG), thinks current events are shaking up the public imagination. They help people understand colonial violence and the reality of genocide, she says, as well as the fact that injustices still continue today.

"Seeing unmarked graves opens the minds of some people who were still in denial about these events," says the law professor at Laval University in Quebec City. "Indigenous people here have been talking for a long time about the colonial genocide they suffered, an idea that is difficult to accept for people who benefit from it but didn’t live it." This tension between the colonized and the colonizers is felt particularly in Quebec. Since the 1960s, nationalists in Quebec have been denouncing the colonialism perpetrated by English-speaking elites following conquest at the end of the 18th century, which is a driving force behind demands for greater autonomy from the federal government. In this context, it has been difficult for people in Quebec to see themselves as oppressors of indigenous people. Indeed, the collective imagination readily celebrates the historical alliances between the First Nations and the French who arrived in the 17th and 18th century, while the English were more belligerent.

In recent weeks, this idyllic vision of the relationship between Quebec and its indigenous population has become more nuanced. Some people are becoming aware that the reality of residential schools also left its mark on this province, even if they were established a little later than in the rest of Canada. "For the first time, Canadians are recognizing that indigenous people were murdered, because they have material evidence," says Guy Lanoue, director of the Department of Anthropology at the University of Montreal. "Up to now, their stories were not taken into account because no political institution was defending them. Now lawyers, indigenous researchers, equipped with the same weapons as white people, can claim this history."

Not yet a revolution

Political scientist Thierry Rodon hopes, like others, that the sympathy towards the First Nations and Inuits, aroused by the discovery of the graves, can become an important element to transform power relations in Canada -- especially since respect for minorities and decolonization are keen topics of discussion since the beginning of the 21st century, particularly among young people. But in order to become more autonomous and regain their dignity, indigenous people must be able to develop their territory, he stresses. For the time being, almost all of it still belongs to the federal government in a country that derives much of its wealth from its natural resources.

"Some negotiations have been going on for years, but the Canadian authorities can unilaterally break them off at will," says Rodon, who holds the research chair at Laval University on Sustainable Development in the North. "Many subsidized programmes for indigenous people were cut in 1996 as part of a drive to slash the public deficit, and the reinvestments are not sufficient to provide enough housing or access to drinking water." So, he says, the current wave of sympathy for indigenous people does not yet feel like a revolution.

Richard Kistabish, a residential school survivor chosen by the UN to participate in a committee to defend indigenous languages around the world, hopes that governments and religious institutions will finally recognize that First Nations and Inuit are excluded from society. "They have to tell us the truth," insists this indigenous activist. "Right now they are cutting down trees, digging mines, and not replacing anything.” Stressing the knowledge, values, and adaptability of the original inhabitants of North America before the Europeans arrived, the 70-year-old dreams of restoring the memory of his parents and ancestors. Once that history is told, it will be time to imagine a present and a future, he says.

With respect to the graves, political authorities seem to have already better understood the message of First Nations and Inuit, who represent about 3.8% of the Canadian population. Both the federal and provincial governments have made it clear that the decision on whether or not to excavate former residential school sites is a community-by-community one. They have allocated special funds to begin the search and, as in Sept-Îles, discussion is underway within each nation as to how to proceed. For now, the exhumation of possible human remains does not seem to be a priority, but rather the need to give these children a burial according to the rites of each community. This is perhaps a way to finally accomplish a mourning that has remained impossible for many decades.