I don’t usually write. My job at Justice Info is to publish the articles written by our journalists, make them look nice visually and publish them on the Internet, giving them as much visibility as possible. I speak a language of acronyms and Anglicisms: AFP, Photoshop, CMS, community management, SEO and so on. But exceptionally, since this event took place in the digital space -- a continent both foreign and familiar to consumers of information on the Internet --, the editorial team asked me to tell this story.

Google: Statistical ally and investigative tool

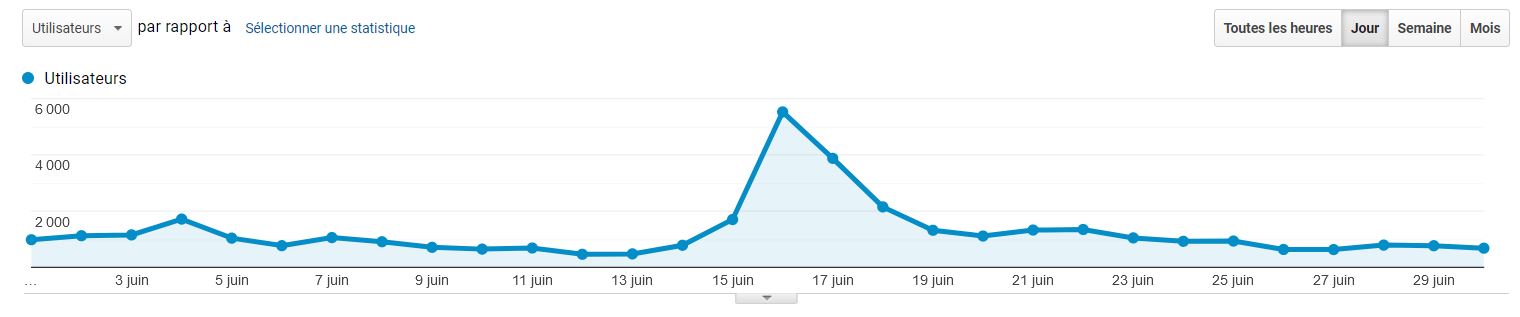

At the end of June, as I produced my statistical report for the month, I saw an unusual peak in the middle of a classic audience curve for our news site. From June 15 to 18, our audience almost quadrupled, with a peak on June 16.

To find out why, I dived into the statistics. The first thing to do was identify the publication on Justice Info that generated all this traffic. Google Analytics, the tool of reference in this matter, indicates that it is the following article, in its English version: "Will Fatou Bensouda face the Truth Commission in Gambia?” It’s a sensitive article because we revealed two testimonies of Gambians, victims of torture under the authoritarian regime of Yahya Jammeh, directly implicating Fatou Bensouda when she held high judicial office in her native Gambia, long before she became the Chief Prosecutor of the International Criminal Court (ICC) in The Hague.

The second question to be answered was: On which platform did this article, which dates from July 11, 2019, suddenly reappear in 2021? This is where the investigation got complicated. After a few minutes of digging through the Google statistics tool, I got some important information. From June 14 to June 30, the article in question accumulated 4,448 "unique views" (the number of different people accessing this page). And 88% of that traffic came from... Facebook. However, we had not republished it on this social network since 2019, even if this article, which remains in our archives, is still well "referenced" on Google.

This led me to a third question: who are these people suddenly reading about Bensouda? It turns out that 73% of them (again according to Google Analytics) have an "IP address" located in the Philippines. An IP address, in our jargon, is the unique identifier assigned to each digital terminal connected to the Internet, making it possible, in principle, to know the place from which this computer or this smartphone connects.

A score of relatively influential "posts”

But why on earth are Filipinos interested in Bensouda's controversial past? To find out more, you have to get out of Google and onto Facebook. By simply typing the English title of our article into the internal search engine of the famous social network, I see that 20 recent posts cite our article. These "posts", in Facebook language, are usually accompanied by a short introductory comment, not always very subtle, written by their Filipino author. Note that these accounts are relatively influential, since the most popular posts generate up to 1,000 likes and several dozen comments.

The Facebook profiles in question are of people living in, or connected to the Philippines. Some are linked to the network of the University of the Philippines, a state university. The "patient zero" (the first of the 20 users to post) has also expressed himself on the alumni group of this university, which has 12,500 members.

One of the profiles in this anti-Bensouda digital hit squad is presented as "Popoy De Vera". This account is easily traced to find his official biography. In 2018, Dr. J. Prospero "Popoy" de Vera was appointed by Duterte as the chairman of the Philippine Commission on Higher Education (CHED). He describes himself as "an academician who has used his technical expertise to assist policymakers, educate the public, and conduct political campaigns".

What’s the connection?

Why would these Filipinos, working mainly in an academic setting, be interested in Bensouda, with the clear intention of discrediting her? Easy: on June 14, the ICC Prosecutor officially requested the opening of an investigation into the bloody "war on drugs" led by President Duterte. The latter had already in March 2018 moved to withdraw his country from the Rome Statute (ratified by every ICC member state) and signalled that he would not collaborate with the court. Bensouda's move therefore sparked a lot of comment in many media outlets, in the Philippines and elsewhere.

Did Duterte himself use the most extensive academic network in the Philippines for an influence operation on social networks? Indeed, aren't Filipinos experts in digital influence peddling? According to a senior Facebook official, quoted by the US newspaper Los Angeles Times, the country is described as "patient zero in the global disinformation pandemic". Or is it more likely that this was a spontaneous operation by a network of pro-Duterte activists, knowing that we are, after all, only talking about 4,500 "unique views" in a country of 108 million people?

The fact that the Facebook "posts" are very similar and all published in the space of three days, allows us to think that there was consultation between these different accounts. It was in any case the second time in less than a year that the Philippines intruded into our statistics. The first intrusion took place during our mock election of December 2020, which allowed our readers to elect, in a symbolic way, their favourite candidate to succeed Bensouda as ICC Prosecutor, with her mandate ending in June 2021. Many Filipinos (often with the same IP address) then voted en masse for the candidate Karim Khan. The British lawyer is now the boss of ICC investigations, including the one on Duterte's anti-drug actions that has just been authorized by the judges. He should probably start preparing already for the end of his digital honeymoon with the Filipinos.

This article was modified on 27/09/2021.