During his appearance before Gambia’s Truth, Reconciliation and Reparations Commission (TRRC) in January 2020, a US-based Gambian professor described former president Yahya Jammeh as “deeply suspicious”, “cynical” and “narcissistic”. His assessment may not be shared by all but most Gambians would agree that Jammeh mastered the art of divide and rule. After two and a half years of public hearings before the TRRC, old scars of Jammeh’s rights violations have reopened and divisions he had sowed resurfaced.

“We found very divided communities especially in Foni,” Jammeh’s birth region, said Tuti Nyang, a reconciliation officer with the Truth Commission. “I remember we went to a community in Foni, and they were saying that at their ‘Gamo’ [annual Islamic gathering] that year, most of their food was wasted because whereas they used to do it as a whole community, different clans decided to not join them. The TRRC was at its peak. Revelations were being made. Accusations and counter-accusations were going on. It broke the community ties. In one community a fight broke out because the victims were being blamed that their stories were made up.”

Communities more divided than ever

“Reconciliation should not be expected as soon as the transitional justice process finishes. It needs concrete steps and actions to be decided, taken and implemented,” said Didier Gbery of the International Center for Transitional Justice, an NGO.

Nyang and her colleagues have held close to 30 peacebuilding meetings in various communities across the country. A few additional person-to-person reconciliation events were organized by the TRRC. Yet for both the Commission and the government, reconciliation has seemed to remain on the back burner. “Reconciliation is at the core of the Truth Commission’s functions but we came into the Commission to do reconciliation jobs with no strategy. There was no foundation. And there was no general consensus on how we want reconciliation to take place in the Gambia,” said Nyang. “The political commitment is not even there for the right reconciliation approach. The communities today are more divided than ever before. If you open a wound and do not clean it properly, it will not heal. The difficult and the uncomfortable conversations need to happen,” she continued.

Yahya Jammeh’s farm in Kanilai

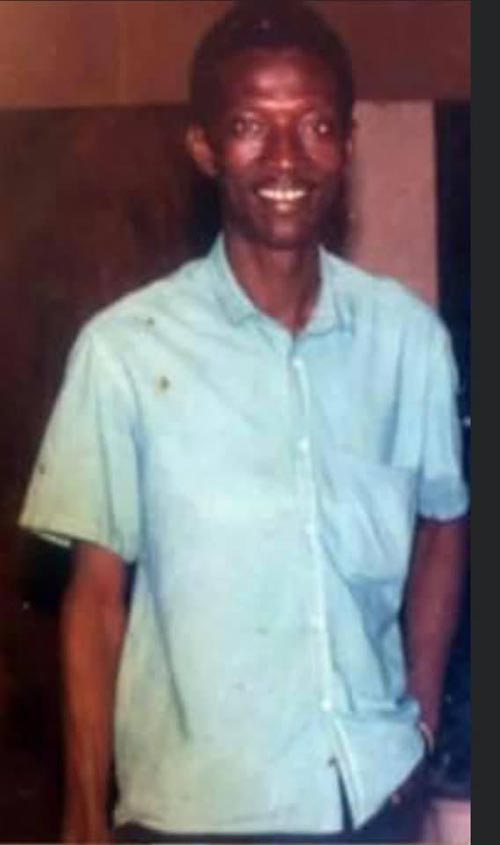

Such sensitive and uncompleted conversations have seemed to affect even the heart of the family of the former dictator himself. Yahya Jammeh’s own family relationships were indeed wrecked after he allegedly killed his cousin Haruna Jammeh and Haruna’s sister Masie Jammeh.

“I used to call my Dad’s phone every day hoping he would pick up,” recounts Isatou Jammeh, a daughter of Haruna Jammeh, in an interview with Justice Info. She has now joined the campaign to bring the former leader – who lives in exile in Equatorial Guinea – to justice.

Yahya and Haruna grew up, with several other cousins, in the house of Isatou’s grandfather, Buruma Jammeh. Buruma, a farmer, was a brother of Jamus Junkung Jammeh, the father of Yahya. Growing up in Kanilai, a town in southern Gambia, bordering Senegal’s Casamance, Yahya lived and worked in the farm rearing animals with his cousins, including Haruna, his biological brother and his sister, Masie.

Masie would grow to be the custodian of the shrine, an important place of worship in the Jammeh family. Haruna would become a manager at a local hotel, a job he kept until 1996.

Yahya started a farm in Kanilai after he took power through a military coup on July 22, 1994. Haruna’s love and skills for farming would come in handy and he accepted the president’s offer to work at his farm, even though his family had cautioned him against it, according to Isatou. Haruna took the job and moved to Kanilai, occasionally visiting his family in Serrekunda, next to Gambia’s capital city, on weekends.

The disappearance of Haruna, Jammeh’s cousin

However, unlike his other cousins, Haruna did not have a very smooth relationship with Yahya and their relations worsened after the president started a witch-hunt in Kanilai in the early 2000s, beginning with his own family. “All the old women in the house, he gave them a concoction to drink and most of them lost their lives,” claimed Isatou. “My Dad was against this.”

In August 2005, Haruna called to tell his wife about his soured relations with Yahya. Isatou was 11. A few days later, he disappeared. His car was found around Kanfenda, a small village about 10 minutes’ drive from Kanilai. Haruna’s brother would occasionally call to assure the family that Haruna was alive and would join them soon. But Haruna never reappeared and rumour kept circulating about his fate.

In 2013, Yahya Jammeh granted a general amnesty, releasing political prisoners. Haruna’s name was 45 on the list. But he was not released. In 2014, the truth began to come out when Bai Lowe, a driver of the ‘Junglers’ — a hit squad on the orders of president Jammeh — gave an interview to US-based Fatu Radio from Germany where he lived in exile. He said he witnessed the execution of Haruna Jammeh. (Last March, Lowe was arrested in Hannover by German authorities.)

Then came the TRRC.

In July 2019, Jungler Omar Jallow confessed to participating in Haruna’s execution. And according to him, Haruna’s sister was also executed a few months later. “Masie was the custodian of the shrine in Kanilai. She was threatening that the gods will be angry with Yahya for spilling the blood of a family member. I think he got irritated because of that,” said Isatou.

The law of silence

“For 14 years, I have not set foot in my village,” Isatou continued. It is a taboo, she said, to even talk about Haruna and Masie in the family. Haruna’s biological brother still lives in Kanilai; he does not talk about it, she said. Suspicion has grown about who may be complicit in the murders. Silence, too, has deepened. Haruna and Masie’s death are said to be ‘God’s wish’, without ascribing blame to anyone.

“The family is so divided because of all these violations,” Isatou lamented. “Sometimes, I worry if I get a husband, who would give my hand in marriage?”

In this context, the main political news this month was the alliance between two former enemies: President Adama Barrow’s National People’s Party and Yahya Jammeh’s Alliance for Patriotic Reorientation and Construction party. The price of this form of reconciliation is said to be to grant Yahya Jammeh an amnesty and allow his return from exile with the benefits of a former president. But “reconciliation is more than Yahya Jammeh coming back to take his assets,” said Nyang. “You are only going to make one part of society happy and antagonize the other part. The Truth Commission was established to right the wrongs. The wrongs haven’t even been properly established, then you bring something else…”