The case of Kazem Rajavi, a prominent Iranian dissident assassinated in the Geneva area in 1990, is worthy of a thriller. Swiss prosecutors linked his murder to agents of the Iranian regime, but they escaped the net. In 2020, as the case was set to be closed, the dead man’s brother appealed, and on September 27, 2021, the Federal Criminal Court ordered that it be reopened as a component of possible genocide or crimes against humanity.

Back last year, when prosecutors in canton Vaud announced that they planned to close the case under a 30-year statute of limitations, lawyers for the victim’s brother Saleh Rajavi appealed on grounds that the murder was "in direct relation with the massacre of 30,000 political prisoners, perpetrated in Iran in the second half of the year 1988 under the cover of the fatwa pronounced by the Supreme Leader Khomeini”. Rajavi’s Geneva-based lawyer Nils De Dardel explains that, “referring to many legal opinions including Amnesty International, we highlighted that this murder was part of the Iranian regime’s plan to kill all active members of the opposition and was linked to the massacre of political prisoners. In this context, it constitutes genocide and crimes against humanity, for which there is no statute of limitations.”

In Switzerland, international crimes like genocide and crimes against humanity fall to the Federal Office of the Attorney General (OAG) to investigate. Canton Vaud referred to it, but the OAG ruled that provisions on genocide and crimes against humanity were not introduced into the Swiss Criminal Code until after 1990 and could not be applied retroactively. The brother appealed again, to the Federal Criminal Court. This court decided differently. Referring to the findings of the Vaud investigation, it concluded that “the assassination in question may indeed have been committed with the intention of committing genocide or crimes against humanity. These crimes (…) can be prosecuted without any time limit. It consequently falls to the OAG to take the case.”

Genocide in international and national law

“Even if it doesn’t go to court, it helps shape the narrative of systematic human rights abuses by the Iranian regime,” says Philip Grant, director of Swiss anti-impunity NGO TRIAL International.

This case spotlights the fact that Swiss law has a broader definition of genocide than international law. Under the 1948 Genocide Convention, genocide is defined as “acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group”. This definition is echoed in the Statute of the International Criminal Court. But some countries take it further. For example, Canadian law says “any identifiable group” and its Truth Commission labelled the residential school system as a case of “cultural genocide” against indigenous people. And in Switzerland, an amendment to the Criminal Code in 2000 considers that genocide can be committed against “social and political” groups.

Swiss international criminal law expert Guénaël Mettraux thinks it would be a “bit of a stretch” to prosecute the Rajavi case for genocide. “If I were a prosecutor in this case, I would avoid unnecessary difficulties,” he told Justice Info. “This case could more easily qualify as a crime against humanity, without the legal and evidential challenges associated with the notion of genocide."

Grant agrees. A prosecution for genocide is “probably not going to happen”, he told Justice Info. A crucial element is “intent” to destroy a protected group “as such”, which has historically been very hard to prove. “It’s much more likely to be investigated for crimes against humanity,” he told Justice Info.

On the other hand, trying to prosecute for genocide could set an international precedent beyond the narrow confines of the Genocide Convention, Mettraux adds. The more countries widen their definition of this crime, the more pressure there might be for it to be widened in international law. “A lot of people are frustrated with how narrow the definition of the Genocide Convention is and think it is important to broaden it to political groups,” he says. Mettraux sees in the decision a sign that Switzerland is committed to upholding international criminal law not just abroad, but also at home.

A crime against humanity?

Crimes against humanity are defined in Swiss and international law as “part of a widespread or systematic attack directed against any civilian population”, with knowledge of the attack.

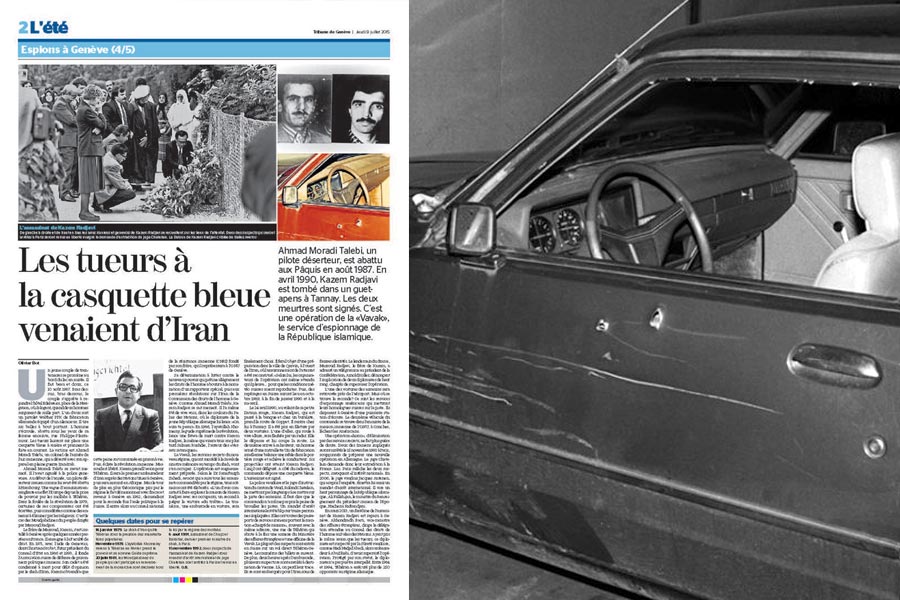

Rajavi was shot dead by a commando, while driving his red Datsun on 24 April 1990. His assassination occurred at a time when Iran’s Islamic regime under Ayatollah Khomeini was not only murdering political opponents in Iranian jails but also killing political opponents abroad. According to the Vaud prosecutor’s investigation, assassinations were notably perpetrated between 1987 and 1993 in Hamburg, Vienna, London, Dubai and Paris, as well as the Geneva area, where Rajavi was gunned down in broad daylight.

After Rajavi’s death, Swiss suspicions focused on Iranian diplomats who had quickly left the country after the assassination. Prosecutors in canton Vaud drew up a list of 13 Iranians suspected of having actively participated in the murder and had them put under international arrest warrants. In 2006, Switzerland also issued an international arrest warrant for former Iranian intelligence minister Ali Fallahian on suspicion of having ordered the assassination.

Two of the hitmen were later arrested by French police. But despite a Swiss warrant, the French government put them on a direct flight to Tehran “for reasons of state”. This drew international condemnation, including from the United States. But the international arrest warrants have now been lifted, and the Iranian authorities have always denied any involvement in the attack.

Given all this, chances of a trial in this case seem low.

A test for new swiss Attorney General?

“Never say never,” replies Grant. Although prosecutions for Iranian political assassinations are rare, he points to the fact that in August a Swedish court started trying a former Iranian official for mass executions of prisoners.

And even more recently, an Iranian opposition group filed a complaint with Scottish police for human rights abuses and genocide allegedly committed by Iran’s current president, Ebrahim Raisi. Hossein Abedini, a member of the National Council of Resistance of Iran (NCRI) coalition of opposition parties, said at a press conference that Raisi had to be held accountable for taking part in the 1988 massacre of some 30,000 political prisoners. The NCRI called for Raisi to be arrested if he travels to Glasgow to attend the UN climate change summit from October 31.

The Swiss case is now in the hands of the Swiss Office of the Attorney General, which is under-resourced on international crimes cases and has been notoriously reluctant and slow to take them in the past. Both Mettraux and Grant think this will be a test for new Attorney General Stefan Blättler.

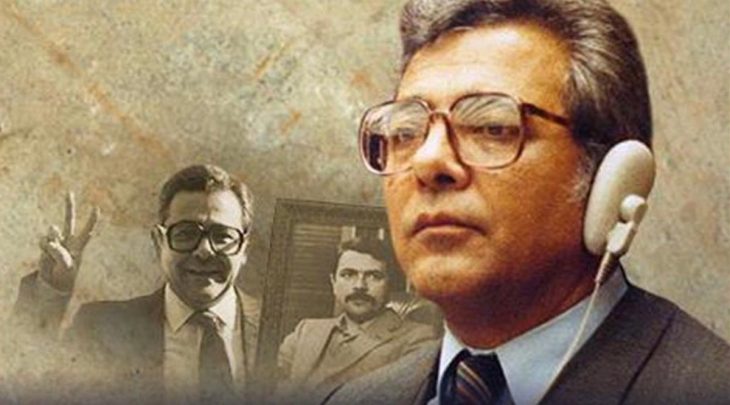

WHO WAS KAZEM RAJAVI?

Kazem Rajavi, post-Revolution Iran’s first ambassador to the United Nations in Geneva, was gunned down on April 24, 1990, as he was driving to his home in Coppet, a small town in canton Vaud near Geneva.

Rajavi had become strongly critical of the Khomeini regime, resigned his diplomatic post after just one year and was the representative in Switzerland of the opposition National Council of Resistance of Iran (NCRI).

He campaigned, including at the UN, for human rights and democracy in Iran. Kazem was the brother of Massoud Rajavi, the leader of the People’s Mujahedin, the main armed opposition group to the Islamic regime in Iran.

The renowned human rights advocate had been granted political asylum in Switzerland in 1981.

Source: swissinfo.ch