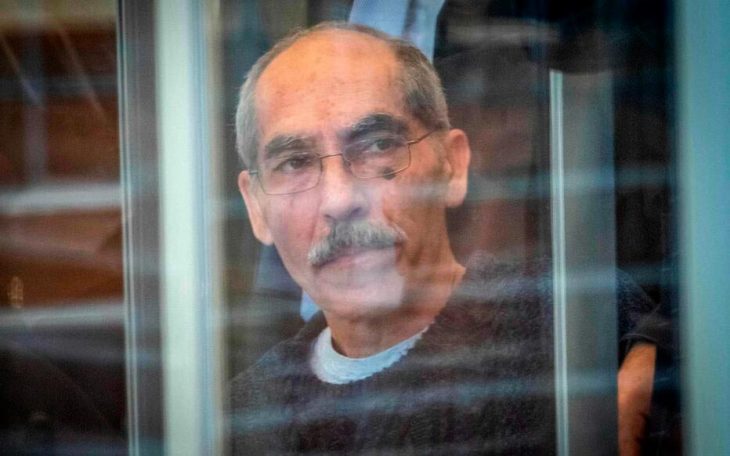

After one and a half years, the Koblenz trial’s final pages are devoted to the defence of the accused. The former Syrian intelligence officer Anwar Raslan and his lawyers have requested witnesses who could speak in his favour. They want to prove, one the one hand, that he had no authority at the Al-Khatib branch in Damascus, where he was head of investigations, and on the other, that he sympathized with the uprising and helped prisoners get released.

The self-portrait that Raslan and his defence lawyers are presenting looks like this: an investigator who believed in doing a good job, but did not agree with how the regime treated the people from 2011 on; a Sunni Muslim who was observed closely by his Alawite bosses, risking his life with any wrong move; an officer who nevertheless helped as many prisoners as he could – so much that he lost the trust of his superiors and was kept in his position without any of his powers; a family father who tried to defect in the early days of the Syrian uprising, but was forced to wait to bring his wife and children to safety.

In these final weeks, after a total of 99 days of trial, the defence is trying to paint a version of the events in which Raslan is not the high-ranking secret service colonel in charge of 58 killings, 4.000 cases of torture and several cases of sexual violence, but instead a man stuck in a position where he tried to do good, while struggling with the loss of his authority.

Helping prisoners where he could?

The first line of defence, as Raslan himself stated in the first month of the trial, is that he was stripped of all authority, after his superiors started doubting his loyalty to the regime. In this scenario, Raslan could not have been responsible for the crimes, even though his rank and position suggest that he was. As a matter of fact, he has not been accused of torturing or killing anyone with his own hands, but of being responsible, as a direct supervisor, for what happened in the secret service Branch 251 in Damascus during the interrogations and in the underground prison.

The second line of defence relies on the defendant’s character. The defence requested several witnesses to come and testify that Raslan had been sympathetic to the revolution, that he would have liked to defect much sooner and that he had helped inmates by treating them well and speeding up their release. Back in May 2020, Raslan had his lawyers read out that “between March and June 2011, I helped prisoners where I could.” He asked the court to ensure that “those who witnessed my sympathy towards the protests and who know my role should be called to testify”, providing a list of 25 names.

An army insider as character witness

One of the names on that list was that of the defendant’s cousin and son-in-law. He testified last July, before the summer break, that Raslan had been accused of sympathizing with the protesters as early as April 2011. “He told me that he felt observed in every moment of his life and that his phone was constantly under surveillance”, the witness said. “He was seen as a sleeper cell, which is why his work was reduced and his responsibilities were taken from him”, he added. Raslan’s relative was reading his whole testimony in high standard Arabic from a piece of paper he had brought to the court and had difficulty answering any questions that went beyond these notes.

Another witness listed by Raslan as someone who “knows what I really thought about the revolution” was a high-ranking army pilot who came from an influential family of military officers in Syria. “I know Bashar al-Assad personally”, he told the court during his testimony last month. The witness defected from the army in summer 2012 and helped Raslan with his defection half a year later. He picked him up from the Jordanian border and arranged an apartment for him and his family. On the car ride from the border town al-Mafraq, that lasted about one and a half hours, they talked. “He said he had not agreed with the regime from the very beginning. He said there was a lot of pressure on him and that he was being observed. He said that there were even officers observing him outside his home”, the witness remembered. When he saw Raslan again a while later, “he said he was very scared that he would be killed. He knew who he had worked for and what they were capable of.”

An officer and a novelist

The same witness explained that, like any defected officer, Raslan was questioned by the Jordanian secret service upon arrival. Later, the defendant met them again to plan a safe route to Jordan for civilian refugees from Syria and provided them with some documents he had brought with him. This was the first mention of internal documents taken out of the country by Raslan and given to foreign intelligence services. Observers and the court have been interested in this detail in order to figure out what Raslan’s political convictions were and whether he really changed sides.

Another defence witness was an Air Force officer turned novelist, who met Raslan during his detention in Al-Khatib in 2011. In his statement in May, Raslan had listed him as one of the prisoners he had helped. The witness said that Raslan had treated him well during the interrogation and had offered him tea and white Kent cigarettes. They had chatted about literature and the witness’s new novel, which the defendant seemed to have read, even though it was prohibited in Syria. “He said he had always dreamed of becoming an author, but that life had taken him somewhere else”, this witness remembered. Shortly after their conversation, the novelist was released. When they met again three years later in Jordan, the novelist said he told Raslan “more than once” that he should make public his knowledge of what happened inside the secret service branches. Raslan declined. “He said he did not like to be in the media, and that one day he would write a book about everything that had happened”, the witness said.

High effort, low evidential value

In addition, during the course of the trial, Raslan’s defence lawyers have repeatedly questioned many of the witnesses, especially insiders, about the power structures inside Syria’s secret services. They have been trying to underline that it was rather based on ethnicity than rank, and to highlight the relations between Sunni and Alawite officers. They wanted to know whether it would have been possible for someone of Raslan’s position to just quit his job, if he chose to, aiming to show how dangerous it was for him to defect.

The defence has requested more witnesses to testify about the loss of authority that they claim their client had suffered within the branch. Some of them have been declined by the court, which considered that the evidential value of their testimonies would be too low compared with the effort to bring them in. For potential witnesses living outside of the European Union, in Turkey or Egypt, it can take months to summon them through official requests. The court also dismissed some of the defence motions, because they were lacking specific information about when and where the requested witness met Raslan, or how they would have had knowledge about his actions.

On its side, the prosecution has repeatedly argued that neither the defendant’s actions after his defection nor his attitude towards the uprising reduced his responsibility for the crimes he is accused of. “A crime remains intentional, even if the expected outcome is undesired”, they said in a statement regarding one of the requested witnesses. As to the prisoners he may have gotten released, they said that this could only prove his willingness to help in individual cases. With some of the defence motions still pending, the date for the verdict remains unclear, but is expected before the end of the year.