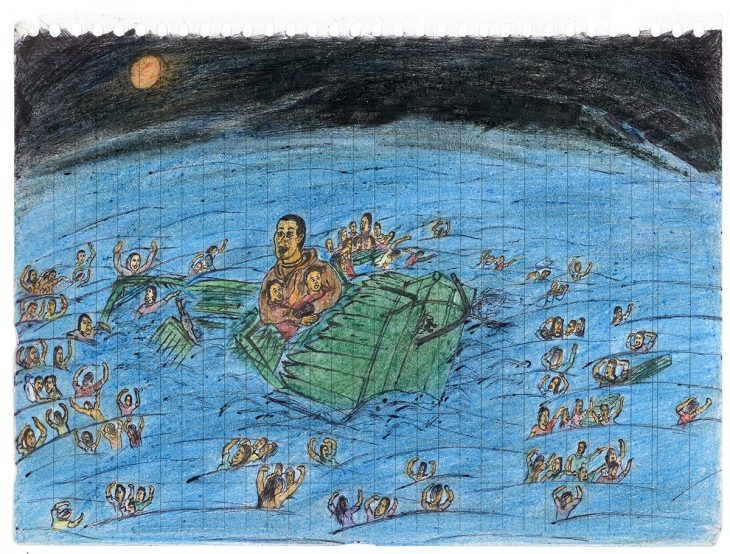

As of December 10, 2021, 22,951 migrants have died or gone missing since 2014 trying to cross the Mediterranean for Europe, according to the International Organization for Migration (IOM). The first half of 2021 shows a record number, with 1,146 people dying while trying to reach Europe, a figure that has doubled in one year. And that is probably far below the tragic daily reality.

The IOM says that two-thirds of the deaths recorded by its teams "are people lost at sea without trace" and that, in reality, "many fatal journeys go completely unnoticed".

As early as 2017, Agnès Callamard, then UN Special Rapporteur on extrajudicial, summary or arbitrary executions denounced "the unlawful killing of refugees and migrants" and pointed to "killings committed by state and non-state actors" creating "a regime of almost widespread impunity". Directly confronted with the influx of people crossing the Mediterranean, Italy initially responded in a concrete manner by launching the Mare Nostrum search and rescue operation. However, due to the lack of support from other EU member states and the cost of this operation, this programme was abandoned in October 2014, leaving the European Agency for the Management of Operational Cooperation at the External Borders of the Member States of the European Union (Frontex) to take its place. Frontex's primary objective is not to prevent loss of life but control borders and fight criminal networks.

Quasi-systematic pattern of human rights violations

Refoulements, inhuman and degrading treatment, arbitrary detentions, non-assistance to persons in danger at sea, enslavement, rape, torture: For the past ten years, NGOs have continued to denounce a quasi-systematic pattern of human rights violations under the 1951 Geneva Convention on Refugee Status, the Conventions on the Law of the Sea, or the Convention against Torture, depending on the case, for people fearing persecution if they return to their country of origin and who find themselves trapped in states like Libya, where they become victims of criminal acts sometimes even more serious.

These same NGOs also provide legal support to victims and initiate proceedings before national and European criminal courts, the UN Human Rights Committee, European and international authorities.

In 2012, the European Court of Human Rights condemned Italy for returning migrants to Libya, noting that the standards for rescuing people at sea and in the fight against human trafficking require states to respect obligations under refugee law, including the "principle of non-refoulement". The Court thus considered that by returning these persons to Libya, the Italian authorities had knowingly exposed them to treatment contrary to the European Convention on Human Rights.

Pressure is now mounting for international criminal justice to take up this issue.

A crime against humanity?

Since 2010, by a vote of the UN Security Council, the International Criminal Court (ICC) has had jurisdiction over international crimes committed in Libya. In November 2020, then ICC Prosecutor Fatou Bensouda said she was continuing her investigations into these alleged crimes, including against displaced persons and foreigners who "continue to be victims of trafficking and crimes such as torture". But can these human rights violations be qualified as international crimes, in particular crimes against humanity or war crimes, and therefore fall under the jurisdiction of the ICC?

A crime against humanity is defined as a number of acts, including torture, slavery, persecution or murder, when committed as part of a widespread or systematic attack directed against any civilian population, with knowledge of the attack, according to the ICC Statute. It must be shown that the multiple commission of these serious acts took place pursuant to or in furtherance of the policy of a State or organization The State or organization must actively promote or encourage such an attack. But in exceptional circumstances, such a policy may take the form of a deliberate failure to act, whereby the State or organization consciously intends to encourage such an attack. The existence of such a policy cannot, however, be inferred from the mere fact that the State or organization refrains from action.

Libya, migrants and the ICC

In June 2019, lawyers Juan Branco and Omer Shatz first sought to target such state policy. In a communication filed with the ICC Prosecutor, they argued that the European Union and its member states were committing murder, inhumane treatment and forced displacement against migrants trying to flee Libya and that this policy was "aimed at stemming the flow of migrants to Europe at all costs, including through the killing of thousands of innocent civilians fleeing an area of armed conflict".

On 23 November 2021, together with survivors, the European Centre for Constitutional and Human Rights (ECCHR), the International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH) and Lawyers for Justice in Libya (LFJL) in turn filed such a communication with the ICC Prosecutor, urging the Court to investigate the responsibility of armed groups, militias and any Libyan state actor in the commission of crimes against refugees and migrants, including arbitrary detention, torture, murder, persecution, sexual violence and slavery. The 250-page communication has remained confidential, but a public summary report has been published by the organisations and is available online. The report explains that the communication is based on the testimony of 14 victims and on investigation reports by the UN Independent Fact-Finding Mission on Libya, Amnesty International and other NGOs, focusing on the Libyan situation in particular. It notes the widespread and systematic nature of the crimes committed against migrants and links them to the official ICC investigation in Libya.

According to these organizations, the conflict has "fostered a growing instability and security crisis in the country that exacerbates discrimination and hostility towards migrants, as well as an extreme worsening of their living conditions. They report that these people are "forced to work for armed groups, including by transporting arms, or even by directly participating in hostilities" and identify links between the main actors involved in the armed conflict and the perpetrators of these crimes. Finally, they highlight a "financial link between the conflict and the systematic exploitation of migrants and refugees, an income-generating activity at the heart of the conflict economy”.

The responsibility of European states

ECCHR, FIDH and LJFL conclude that these contextual elements testify to the existence of a state policy against migrants and refugees, thus qualifying these crimes as crimes against humanity. They specify that most of these crimes took place in the context of an ongoing armed conflict and therefore constitute war crimes. Finally, they add that "EU policies have trapped migrants and refugees in Libya and thus contribute significantly to this grave situation”.

Does this mean that European leaders are accomplices in a crime against humanity or a war crime? The NGO report does not go so far. It analyses European policies and their impact but does not, at this stage, qualify the involvement of European actors in complicity. It focuses on the contextual elements, the qualification of the crimes and the responsibility of the highest officials in Libya.

The qualification of war crimes for acts committed against migrants in Libya has already been advanced in an op-ed by Alessandro Pizzuti, co-founder of the NGO UpRights, following the arrest on 14 October 2020 of a coastguard commander, Abd al-Rahman al-Milad (aka "al-Bidja"), on charges related to human trafficking and oil smuggling.

Qualifying war crimes

War crimes include a number of acts such as wilful killing, torture, inhuman treatment, unlawful detention committed in the context of and in connection with armed conflict. Alessandro Pizzuti recalled the findings of the UN experts on Libya that al-Milad is linked to the Shuhada al-Nasr Brigade, an armed group controlling the al-Zawiya oil complex and the al-Nasr migrant detention centre in al-Zawiya, on Libya's west coast. The UN panel stated that migrants intercepted at sea by al-Milad, as commander of the coast guard in al-Zawiya, were transferred to the al-Nasr detention centre, where they were allegedly held in inhumane conditions and subjected to the following acts: systematic torture, inhuman and degrading treatment, including against minors, and sexual exploitation, including the sale of some women as sex slaves.

UpRights believes that these human rights violations against migrants meet the necessary criteria to qualify as war crimes before the ICC: existence of a non-international armed conflict since 2011, relevant criminal acts perpetrated in connection with the armed conflict.

The issue is tricky, to say the least, as the aim is to demonstrate a link between the criminal conduct and the armed conflict, to show that the armed conflict played a substantial role in the perpetrator's ability to commit the crime, his decision to commit it, the purpose for which it was committed or the manner in which it was committed. This includes demonstrating that human trafficking would be a resource for the armed group Shuhada al-Nasr and that these crimes are committed to finance military operations.

But it is at least one more reason for the ICC Prosecutor's office to start investigating the financing of this group and the use of this financing.

On 23 November 2021, Karim Khan, who replaced Fatou Bensouda as ICC Prosecutor last June, presented his report on the situation in Libya to the UN Security Council. He cited reports of violent raids on migrant camps in Tripoli, and noted arbitrary arrests and detentions of migrants, including women and children. It is known that a cooperation agreement between the ICC and Europol is in the process of being signed, the purpose of which is to identify those responsible for crimes committed against migrants. But it seems for the time being that the Prosecutor does not want to pronounce on a possible qualification of crime against humanity or war crime, which Chantal Meloni, senior legal adviser of the ECCHR, and Xuchen Zhang, researcher within the same NGO, noted in an article published a few days later on the OpinioJuris website

Not only the Mediterranean sea

Pressure on the ICC Prosecutor, as well as on national judicial bodies, is unlikely to abate. Libya and the Mediterranean are certainly at the centre of the drama and initiatives to ensure that criminal responsibilities are established. The number of migrants missing in the Mediterranean accounts for half of the migrants missing worldwide since 2014, according to the IOM. But the problem is not limited to this region.

On November 24, 27 foreigners trying to reach the British coast died in the English Channel after their boat sank, a tragedy that calls into question the policies of France and the United Kingdom on foreigners and asylum seekers in Europe. On the other side of the world, Australia, the first state to implement a policy of outsourcing the reception of foreigners, is also targeted by another communication filed with the ICC by a group of legal experts, in collaboration with the Stanford University Law Clinic and the NGO Global Legal Action Network. They call for an investigation into the inhuman and degrading treatment, sexual violence and arbitrary detention - which they describe as crimes against humanity - committed over decades against foreigners in closed offshore facilities established and maintained by the Australian authorities.

The European Union's policy of outsourcing its border control (in other words, subcontracting the control of entry into European territory) and creation of artificial shields like Turkey to oppose the arrival of foreigners, asylum seekers and refugees on its territory, creates situations of extreme risk. This short-term policy, without any reflection on the question as a whole, seems to be a way of absolving itself of a responsibility that European states assumed when they signed the 1951 Refugee Convention, namely that of protecting anyone who flees their country of origin for fear of persecution.

It is therefore up to the ICC Prosecutor and national judiciaries to address the causes and entities responsible for this situation, in the interest of truth and justice.

Jessica Lescs is a lawyer at the Paris Bar, practising in the field of asylum law and international criminal law. She represents the interests of FrontRights, an NGO that helps migrants and victims of human rights violations particularly in the Mediterranean to bring cases before national, regional and international authorities and courts to identify the perpetrators of these violations and seek redress.