“I present my feelings of forgiveness for the great pain caused by the execrable acts committed (...), which led to the deaths of innocent people who were marked as combatants, leaving deep desolation among their loved ones. To them I offer my absolute willingness to contribute to the clarification of the truth, as a means of redress”, wrote Paulino Coronado, a retired general and former commander of the Colombian army’s 30th Brigade, in the letter he sent to the Special Jurisdiction for Peace, locally known as the JEP.

November and December saw a flurry of movement in the first case opened by the judicial arm of the Colombian transitional justice that focuses on deeds committed by Colombian state agents. Twenty one former Army officials among them one civilian formally accepted the charges brought against them for having murdered 247 civilians and then unlawfully passing them off as rebels killed in combat, a tragedy that has appalled Colombians for over a decade and that became euphemistically known as ‘false positives’.

A second significant achievement for the JEP

Seven high-ranking officers – four colonels and three majors – joined General Coronado in accepting that these extrajudicial executions amounted to war crimes and crimes against humanity, as the tribunal noted in its two July indictments. This marks the first time that state actors acknowledge their responsibility for crimes committed during the country’s 52-yearlong armed conflict within the transitional justice system stemming from the 2016 peace deal with the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC).

This is the second significant result for the JEP this year, after seven former FARC commanders accepted the accusation against them over thousands of kidnappings. The arraignment hearing in which they will formally accept the charges, including that these abductions amounted to war crimes and crimes against humanity, has been moved forward a couple of times due to victims’ observations and legal motions. It will likely be held during the first two months of 2022.

In an interesting twist, three of the first 25 indicted state officials did not accept the JEP’s charges, meaning the macro-case on false positives will simultaneously advance along the tribunal’s two tracks. While the majority will qualify for 5-to-8 year sentences in a non-prison setting, provided they contribute with the truth and personally redress victims, the three reluctant colonels will see their case move to adversarial proceedings where, if found guilty, they will be handed down 15-to-20-year prison sentences.

More to come

Last July, following three years of investigation, the JEP unveiled two indictments in the ‘false positive’ case, which exhaustively detail the different modus operandi and strategies used to present civilian homicides as “fictitious operational results”.

The tribunal first charged six officers, three non-commissioned officers and one civilian with 120 extrajudicial executions, 24 forced disappearances and one attempted murder in Catatumbo, a mountainous zone on the border with Venezuela between 2007 and 2008. Then it followed up with a second indictment, charging eight officers, four non-commissioned officers and three soldiers with 127 similar executions in the northern Caribbean coast between 2002 and 2003.

For their role in what it described as “criminal organizations embedded within military units”, the tribunal accused them of the war crime of “wilful killing of protected persons” and the crimes against humanity of homicide and forced disappearance. The JEP’s justices also charged them with homicide of protected persons and forced disappearance under Colombian law. In both cases, it underscored that all victims were civilians and that therefore the military had a legal duty to protect them, as well as eight rebels killed by soldiers after being wounded in combat or turning themselves in.

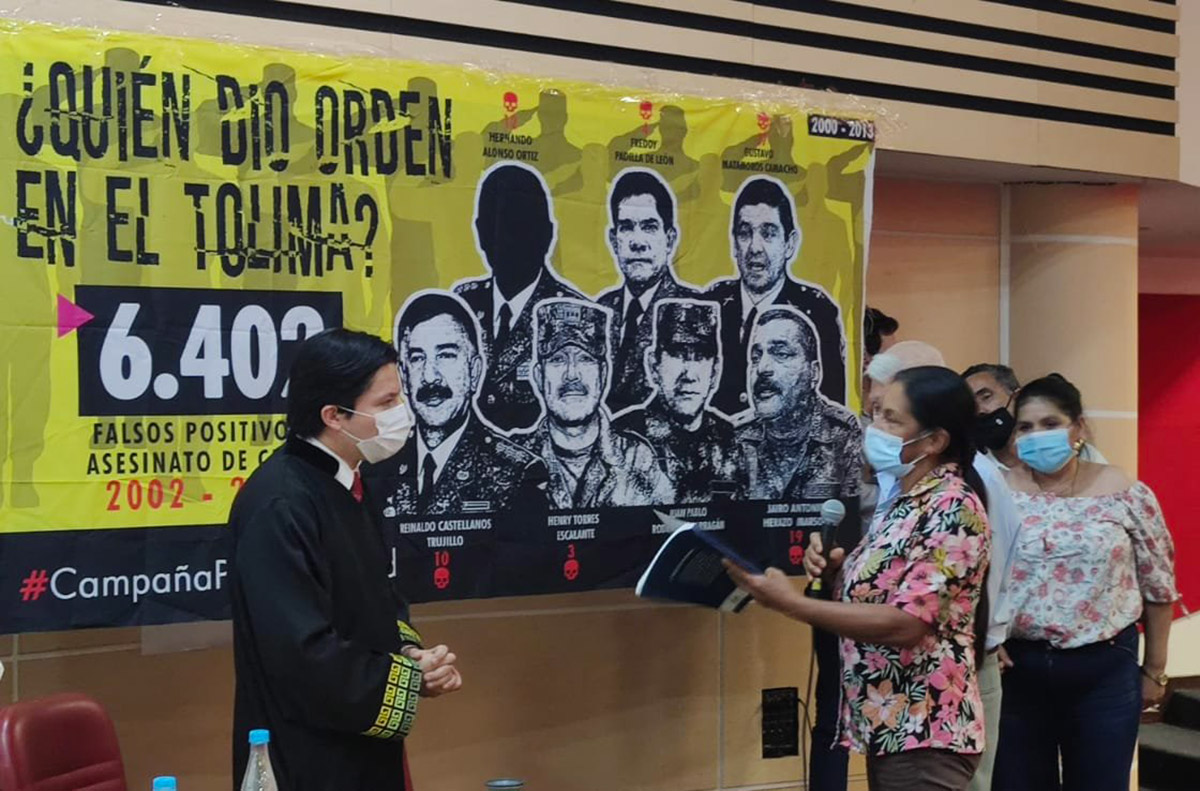

These two indictments are part of a broader probe on extrajudicial executions from 2002 to 2008, a six-year period coinciding with Alvaro Uribe’s administration in which the special tribunal deems that at least 6.402 such murders took place. In March, the JEP laid down its criteria to build the case and explained which specific regions, military units and years it will focus on to illuminate the broader criminal pattern. In line with this approach they termed “from the ground up”, justices will first present indictments in six sub-cases – beginning with these two – and use these to glean information on the underlying patterns of behaviour and the institutional norms and culture that allowed such crimes to occur.

This means that after bringing charges against these and other officers with regional command, the JEP will then present its case against those most responsible at the top, potentially including members of the top brass of the Armed Forces and the Defence Ministry during those years.

A striking change of heart

“I own up to my responsibility for having contributed to the armed conflict instead of to peace, as my duty as a public servant and a citizen demanded of me. I ask forgiveness to each citizen who was a victim of my actions, whom I recognise as dignified persons and subjects whose rights were violated, and I commit myself to redress them by providing the complete truth known to me about these murders”, retired major Guillermo Gutiérrez Rivero wrote, according to excerpts made available by the JEP.

Gutiérrez, chief of operations of the 2nd Artillery Battalion ‘La Popa’ that operated in the northern departments of Cesar and La Guajira, was implicated by the JEP in the execution of several Kankuamo Indians. But as recently as October 2019, he denied before the tribunal having had any knowledge or responsibility of the executions carried out by his military unit.

But it’s perhaps General Coronado, the highest ranking military indictee so far, who has shown the most striking change of heart. Forced to retire in 2008 when the scandal was uncovered, the general initially insisted that victims were “outlaws” and later on denied any involvement. After being accused of “wilfully failing in his duty to prevent the commission of these crimes”, Coronado – who had not requested admission to the JEP at the time of the indictment – is now calling on former colleagues to come around like him. “My acknowledgement is also a call to leaders and all those who have held positions of command and power in our country to reflect on what they failed to do or allowed to happen by endorsing, probably in good faith and overconfidence, those disastrous actions that are now fully known and accepted by the perpetrators”, he wrote.

Three reluctant colonels, including a presidential candidate

In stark contrast, three officers rejected the JEP’s findings and refused to acknowledge their responsibility over the crimes they were indicted for, meaning that their cases were referred to the tribunal’s prosecution unit and will probably head to a trial.

Chief among them is colonel Hernán Mejía, who commanded La Popa battalion between 2002 and 2003 and who was the first major officer taken off duty over this scandal. According to the JEP, he “took advantage of his rank and position as battalion commander to form a criminal organisation that he also spearheaded” and “his orders were executed by battalion officials who were part of this organisation”. Mejía – who declared himself a presidential candidate for 2022’s election and has been defended by former president Álvaro Uribe and members of his party – rejected the tribunal’s charges, arguing that the Attorney General’s Office stole his military unit’s original documents and staged fake witnesses.

Two other colonels will join him. José Pastor Ruiz – who was an intelligence officer at La Popa and had remained silent when called before the JEP – filed a request for annulment arguing that the tribunal didn’t have jurisdiction over his case and asking to remain within the ordinary criminal justice system. The tribunal rejected his motion on the grounds that it has overriding and preferential jurisdiction over members of the security forces.

In another intriguing turn of events, colonel Juan Carlos Figueroa – who succeeded Mejía at La Popa and was considered a fugitive since leaving Colombia for Paris in July 2019 and never responding to justices’ calls to the stand – reappeared after the indictment against him. In a written statement submitted by his lawyer, Figueroa informed the JEP that he currently lives in the United Arab Emirates and rejected the tribunal’s accusation that, “once he became aware of the criminal organisation in place (…), far from deactivating it, he took up its leadership” and “used pressure and various incentives to get his subordinates to report such combat casualties”. In view that he chose not to accept the charges, the tribunal also referred him to the prosecuting unit.

The victims’ long wait

With the decision by 21 former Army officials to accept the JEP’s charges, Colombia may get closer to providing victims of extrajudicial executions with the truth, justice and redress they have been seeking for as long as two decades. In total, 984 victims are accredited as parties to the case, usually relatives of the young men aged 25 to 35 who were executed. Several hearings over the past few months organised by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, the extra-judicial arm of the transitional justice, have also seen an increasing number of former soldiers owning up to their roles and asking for forgiveness. In February or March, when the arraignment hearing before the JEP will probably be held, hundreds of victims will finally get a chance to hear their acknowledgement and their regret in person.