"I have only four days to answer all the lies against the Iranian people," Hamid Noury said in Stockholm District Court on November 23. This is the first time the 60-year-old has spoken, three months after his trial began. Accused of war crimes - including torture and inhuman treatment - and murder, the former Iranian prison official is alleged to have played a significant role in summary executions carried out in the summer of 1988 in several prisons in Iran.

From July to September 1988, on the orders of Ayatollah Khomeini, the spiritual leader of the 1979 Islamic revolution, thousands of prisoners - former sympathizers of the Islamo-Marxist People's Mujahedin organization or left-wing political activists - were executed after a summary judgment handed down by "death committees" made up of a clerical judge, a prosecutor and a member of the intelligence services. In Gohardasht prison, near Tehran, "at least 600 to 700 people" were killed in the space of three months, according to Swedish prosecutor Kristina Lindhoff-Carleson. And it is in this prison that Hamid Noury is said to have officiated as an assistant to the representative of the prosecutor and, in this function, participated in the selection of prisoners sent before the "death committee".

The former civil servant dismisses these accusations completely. His lawyers got authorization for him to first give evidence without contradiction, before being questioned by the prosecutors. He not only denies his involvement, but also implies that the massacres themselves did not take place.

"Fictional and fabricated”

During the last quarter of 2021, there was a succession of witnesses and victims in court. In early November, the court also travelled to Durrës, Albania, to hear six civil parties and several witnesses. These members of the People's Mujahideen now live in the new city of Ashraf 3, where several hundred of them found refuge in 2013, after leaving Iraq, where they had become persona non grata following the fall of Saddam Hussein. There, they live in suspense, waiting for the fall of the Mullahs. Exiled without refugee status, the witnesses in Hamid Noury's trial cannot leave Albania for lack of a passport, explains their lawyer Göran Hjalmarsson. The Swedish court therefore went to them.

In Stockholm and Durrës, some told of their detention, of torture, of death row, and of fellow detainees who were taken away and never seen again; others told of their relatives who were arrested and disappeared, of the silence of the Iranian administration, and of the absence of a grave to mourn over. Noury listened carefully to all these testimonies. “He is very serious [during the hearings]," notes Göran Hjalmarsson, one of the lawyers for the civil parties. “He takes notes, he compares the testimonies in court with those given to the police. He really wants to prove they [the witnesses] are lying.”

And when the court finally gave him the floor on November 23, the former official denounced "fictitious and fabricated stories", reports AFP. "When we go into the details, we see that they do not hold. I will put an end to 33 years of lies," he assured the court. For if Noury's speech is political, patriotic in the extreme vis-à-vis the regime, the accused denies having participated in anything, saying he was not even present in Gohardasht that summer.

Traumatic memory and the passage of time

From the beginning of the trial, the question arose as to whether the 60-year-old man was the man the witnesses were talking about. In the Iranian prison, Noury worked under the pseudonym of "Hamid Abassi". To remove any ambiguity, the prosecutors presented the judges with a screenshot of a message sent by the accused to an official at Evin prison in Tehran, signed "Hamid Noury/Abassi".

At the end of November 2021, the accused did not deny having used this pseudonym. What he denies is that he was an employee of the prison of Gohardasht in 1988. It was in Evin prison that he worked that year, he says, a job for which he described himself as "talented", declaring that he always showed courtesy to the inmates. As for what supposedly happened during that fateful summer, he could not have participated because he was on vacation at the time, he maintains.

“He can deny, but we have dozens of witnesses who recognize him without any doubt,” replies Hjalmarsson. “This is traumatic memory, images, events that cannot be forgotten, even if you wish you would.” For their part, defence lawyers believe that the passage of time casts doubt on the credibility of the testimony implicating their client.

"Who could have imagined that?"

Iraj Mesdaghi is certain of his memories, saying Noury is indeed the man he met many times in the corridors of Gohardasht prison in 1988. A former supporter of the People's Mujahedin, the 61-year-old writer and human rights activist spent a decade in Iranian jails before fleeing his country and seeking refuge in Sweden.

He returned to Iran in 1979 after years of exile in the United States to participate in the great upheaval of the Islamic Revolution. Like many Iranians, Mesdaghi believed that the fall of Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi would put an end to the dictatorship. This hope was quickly dashed by the violence of the new regime. The activist then became close to the People's Mujahedin, former allies of Khomeini who had become virulent critics of the government. In the summer of 1981, after a big demonstration and the death of 72 people in an attack - attributed to the Mojahedin by the government - thousands of people were arrested, including Mesdaghi. Sentenced to 10 years in prison for "sympathy" with the organization and "refusal to cooperate" with investigators, he went from one prison to another, from cell to torture room.

In summer 1988, he was in Gohardasht prison. “On the first day of the executions, I was in solitary confinement,” says the 60-year-old. “They came to take me, along with the others in solitary cells and they took us to a corridor. We didn’t know at the time, but we were the first group to be taken to the ‘court’, the death committee.” The prisoners waited, blindfolded. A prison official asked what they were doing there, who brought them, complaining that he was not consulted. “Because he wanted to show his authority, he sent us back to our cells. We didn’t go to the committee that day. If we had, we would all be dead,” states Mesdaghi in a calm voice. “We would have been sent to the committee, where they would have asked questions and we would have answered as usual, without imagining at the time our answers would send us to death. Who could have imagined that?”

That night, from the barred windows of his cell, Mesdaghi saw guards over-excited by something going on behind a wall. “We realized later that’s where the executions started. Then they were transferred elsewhere, in the prison amphitheatre.”

The crime archivist

During the following weeks, the prisoner and his comrades gradually guessed what was happening. Fellow prisoners were taken away and never seen again. Food rations became more abundant. There was that guard who one day, while waiting in the corridor, Mesdaghi saw coming back from the amphitheatre carrying the personal belongings of detainees taken away earlier and that no one would see again. And there was the cheerful look of the prosecutor's representative in Gohardasht, a man named Nasserian, whose real name is Mohammad Moghiseh, and his assistant: Hamid Abassi/Noury.

That one, Mesdaghi says he is sure of his real name. He got it, he says, from a fellow prisoner who was taken to be beaten. "During the torture, Noury's identity card fell, and my friend was able to see his name. He told me as soon as he was brought back to our cell, after being put in solitary confinement," says the former prisoner. Mesdaghi is also certain that it was this man, now in the dock, that he met again and again in the corridors of Gohardasht. He remembers seeing him coming back, smiling, from the amphitheatre, distributing cakes and sweets to the prisoners lined up on death row "as if he wanted us to join the party”.

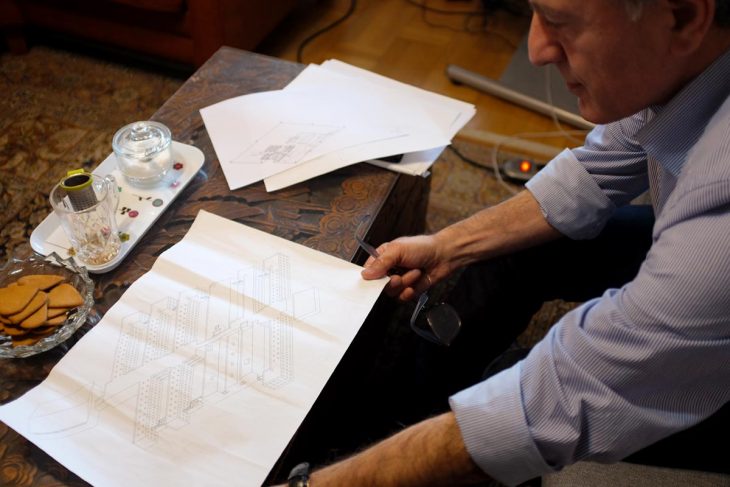

When Mesdaghi tells what happened that summer, he becomes animated and sometimes laughs nervously as he recounts the horror. In the living room of his apartment in the suburbs of Stockholm, he shows us maps of the prison to show exactly where he was, when he was there, and how he could have witnessed this or that scene. He fetches a traditional Iranian towel, a long woven strip similar to the one each inmate had in prison, and blindfolds himself with it to show how, through the threads, he could observe without the guards suspecting he was seeing. His account is an infinite profusion of details, of precise explanations, sometimes making us feel dizzy.

Four times Mesdaghi was sent before the "death committee", and four times he escaped, partly by cunning and partly by luck. Thirty-three years later, he is still surprised. Released in 1991, he fled with his family through the mountains, towards Turkey and then, they hoped, towards the United States. But his wife, sick, was hospitalized in Turkey, needing treatment. The United Nations High Commission asked Sweden for an emergency humanitarian visa on their behalf, and Sweden accepted them. Since 1994, the family has been living in the suburbs of Stockholm, on the Baltic coast, thousands of kilometres from their country of origin.

But the past still haunted them. Mesdaghi has spent the last 30 years documenting the 1988 massacres that the Iranian state continues to deny, with articles, books, an autobiography and detailed plans. When asked why such an obsession, he answers simply: “Because I am alive and my friends are not.” He has spent his whole life trying to let people know what happened. “I hoped, but I didn’t really believe there would be a real trial one day. That is why I went to the Iran Tribunal [court of opinion on the 1988 massacres whose sessions were held between 2007 and 2012 in London and The Hague].”

The trap

In autumn 2019, Mesdaghi received a text message from an unknown person who said he had read his work. "I know someone you know," the mysterious correspondent wrote, leaving his phone number. The activist called him immediately. On the other end of the line, the man, who introduced himself as "Heresh" and lives not far from Stockholm, asked him, "If I send you a picture, could you tell me who it is?" Mesdaghi immediately recognized the man in the image sent via Whatsapp and replied, "This is Hamid Noury, aka Hamid Abassi". The two men agree to meet the next day.

Heresh is Noury's son-in-law. He lives in Uppsala, not far from Stockholm, near his estranged wife and daughter. A family dispute about his daughter's future had led him to look into Noury, with whom relations had become increasingly difficult. This research led him to Mesdaghi's work and to the discovery of the dark past of the man who was his father-in-law. Mesdaghi realized that he had an unhoped-for opportunity to lure Noury to Sweden to be tried for his crimes under universal jurisdiction.

The two men set up a trap. Heresh wrote to his ex-father-in-law, claiming to have changed his mind and wanting to make amends. He proposed to pay for a plane ticket to Sweden so that they could talk and even booked a stay in southern Europe to entice him. Meanwhile, Mesdaghi went to London to meet up with lawyer Kaveh Mousavi, an acquaintance of his, and his colleague Rebecca Mooney, as well as a friend, documentary filmmaker and Iranian refugee Nima Sarvestani. Together with two other victims, they set up the basis of the legal case and contacted the Swedish lawyer Hjalmarsson. The complaint was filed and prosecutor Kristina Lindhoff-Carleson opened an investigation. A few days later, on November 9, 2019, Noury landed at Arlanda Airport in Stockholm, and was arrested by the police as he got off the plane.

Noury is certainly not Ebrahim Raissi - the current Iranian president, who is suspected of having been a member of one of the "death committees" when he was a deputy prosecutor in Tehran in 1988. Noury was not a member of these committees. But when asked about the former prison official's alleged responsibility, Mesdaghi shakes his head. “Noury may not have had the authority to take the decisions himself, but he really tried to get involved in the selection of the people who would be executed and to give information to the committee about us. Everybody who went to the court had two dossiers - a formal, administrative one about the investigation, the sentence etc., and the other one was about the activities in prison. The second one was prepared by Nasserian and Noury. That is how Noury had a very active role in the executions,” says the former prisoner.

The trial is expected to continue to April 2022.