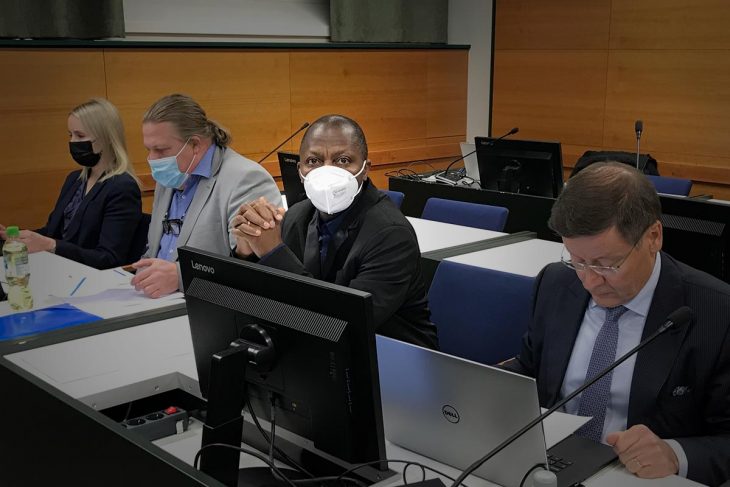

In private, players in the trial of Gibril Massaquoi say they have lively debates. But in public, they practise exemplary Nordic justice, with impeccably restrained, unemotional words. Defence closing arguments on January 24, in a small courtroom in the snow-covered southern Finnish town of Tempere, was no exception.

Here there is no appetite for fancy gowns and flights of eloquence. No wigs or ermine, just ordinary suits and ties. Here one does not stand before the judges or flatter them with a thousand courtly bows; everyone remains seated, ignoring excesses of form and sticking strictly to the facts. In this part of the world, where the collective aspiration is egalitarian, there is little taste for frills. To have ambition is noble; to want to show off is frowned on.

What is striking in this trial is a total contrast between the measured debates and the bitter, irreconcilable difference between the two sides’ versions of the story.

Mysterious and suicidal odyssey

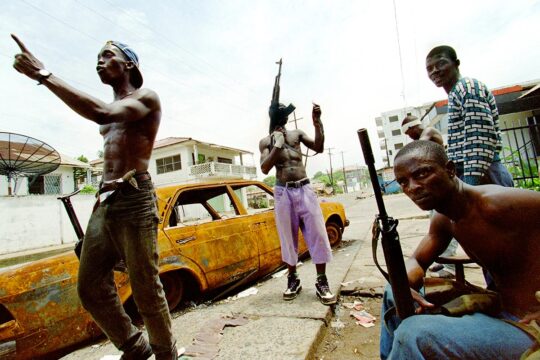

Since July 2021, prosecutor Tom Laitinen has been pursuing a theory that turns on its head historical knowledge of the end of the 1990s civil wars in West Africa. After wavering on the dates when some of Massaquoi's alleged major crimes took place, the prosecutor made up his mind. He told the court that the killings and rapes he accuses Massaquoi of committing in the Liberian capital, Monrovia, took place during the "summer" of 2003, between June and August. He therefore requested a change in the time period covered by the trial, which was initially from 1999 to March 10, 2003. It now extends to August 18, 2003.

Until then the parties had agreed that Massaquoi, who in 2002 became a key informant for the prosecutor of the Special Court for Sierra Leone and was under that UN-backed tribunal’s protection from March 10, 2003, could not have been in Liberia after that date.

Now, however, the prosecutor claims that Massaquoi could have deceived UN security in Freetown and travelled several days to Monrovia to commit massacres alongside Liberian president Charles Taylor's men. This is despite the rainy season that was at the time ravaging the tracks between the two countries, and despite the fact that Massaquoi had betrayed Taylor before the UN tribunal and Taylor had already physically eliminated several other senior Sierra Leonean commanders who had compromised him.

The advantage of the prosecution's case is that it fits with the historical facts described by witnesses about the Monrovia massacre at the heart of this trial. Indeed, the massacre can only have occurred during the three months in 2003 that preceded Taylor's fall. The difficulty is that the prosecutor's thesis requires that Massaquoi embarked on a journey as mysterious as in an Ian Fleming novel: he left his comfort and protection in Sierra Leone for a mission described as "suicidal" by the American researcher Corinne Dufka, a specialist in the region who delivered Massaquoi to the arms of UN prosecutors in August 2002. And the prosecution has not provided any concrete, substantiated proof of this "mission impossible".

Hence the deep unease that now affects this case. If Massaquoi is convicted of these crimes, it will mean that Finnish justice has emancipated itself from the accumulated historical knowledge on this period and its actors. If Massaquoi is acquitted, there will be questions about the investigations and how the prosecutor arrived at a thesis that was inconceivable a few months earlier.

Back and forth of dates and witnesses

The credibility, even integrity, of the investigations is a common thread in the arguments of Massaquoi's lawyer Kaarle Gummerus. He recalled that the case was initiated by two partner NGOs, Civitas Maxima (Switzerland) and Global Justice Research Project (GJRP, Liberia), which in 2018 sent the first evidence against Massaquoi to police in Finland (where Massaquoi has resided since 2008, following an agreement between that country and the UN). It was these same NGOs that helped the Finnish team find witnesses, Gummerus told the court.

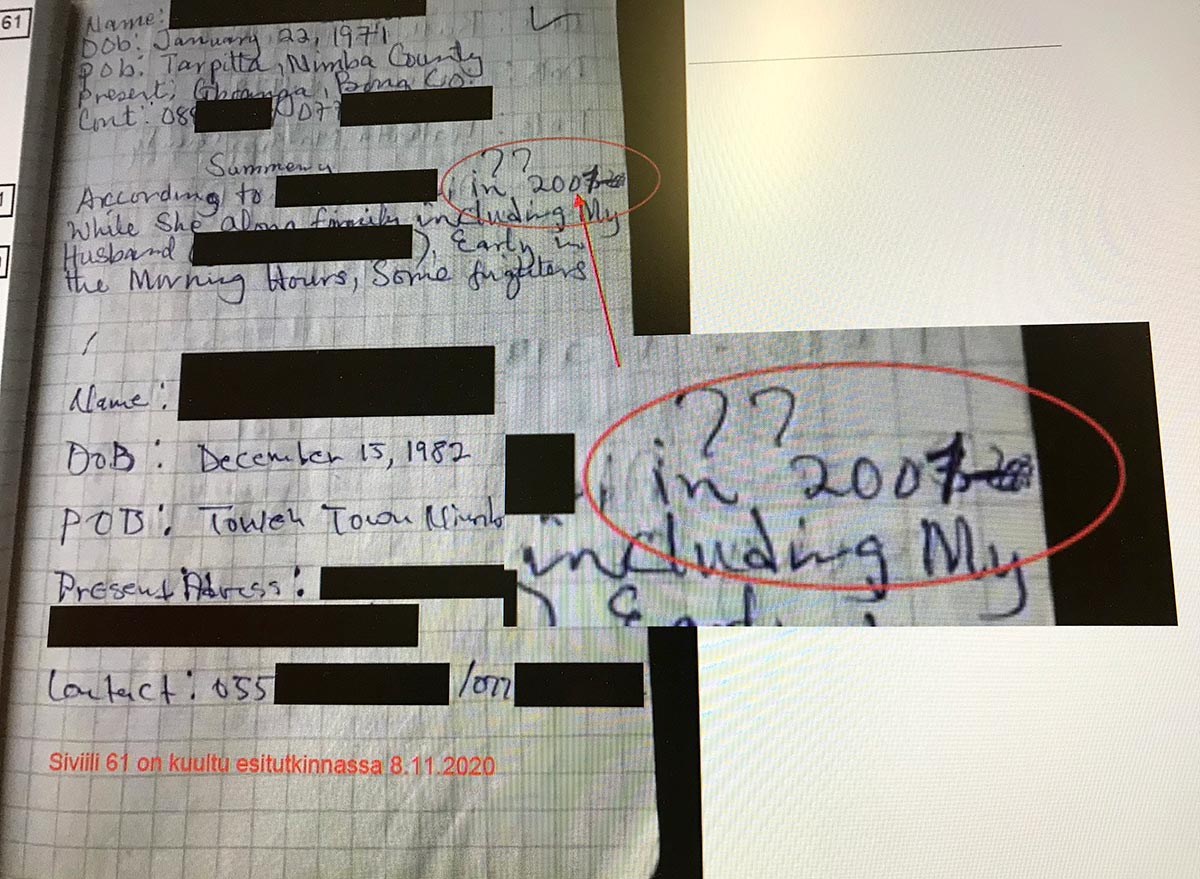

The lawyer listed the missions of Finnish police officers to the field and described how they gradually built up the case. The first trip, in January-February 2019, focused only on Lofa province, where the NGOs had collected incriminating testimony for crimes presumably dating back to 2001. The second trip, in March-April, saw a Liberian member of the GJRP join the Finnish investigative team. According to Gummerus, no witness could initially identify Massaquoi on the set of photos presented to them. The third trip took place to the United States, for an unsuccessful search of press clippings from the time. The fourth mission, in November-December 2019, heard 48 witnesses in Liberia, eight of whom identified Massaquoi in photos. They were all from Monrovia, the lawyer noted. The fifth fact-finding mission, in October-November 2020, took place six months after Massaquoi's arrest in Finland. The case had been in the media. This time, the lawyer said, the 39 new witnesses all recognized the accused in photos.

The Finnish investigation had now also broadened its scope to include crimes that took place in the heart of the Liberian capital. Gummerus described the back and forth of testimony about Massaquoi's alleged involvement in Monrovia: he said the first witnesses put the atrocities in 2003, then changed their testimony in court to 2001 or 2002, before a new group of witnesses said they indeed took place in the "summer" of 2003. "This radically changed when defence witnesses said in Freetown that Gibril Massaquoi was in a safe house” under UN protection, and after a historian called as an expert witness definitively clarified that the LURD (Liberians United for Reconciliation and Democracy) rebel attack on the Liberian capital could not have happened before 2003.

The battle of Monrovia thus appears to be the central battle in this trial. "The court should say which of the prosecutor’s versions is more credible, or dismiss it,” Gummerus told the court.

“Alternative” truth on Lofa crimes

The defence knows, however, that the case against Massaquoi for crimes in Lofa province, northern Liberia, is more difficult. Its main weapon is investigations by human rights organizations into the same massacres, either just after the events in late 2001 or six years later. In these investigations, carried out in particular by Human Rights Watch, none of the dozens of testimonies collected mention Gibril Massaquoi or "Angel Gabriel" (his nom de guerre, unknown before this trial) as one of the commanders who perpetrated the massacres, while the names of other warlords do appear. "There is therefore an alternative version," to that of the prosecution, collected just after the events and not nearly 20 years later, explained the lawyer.

In summing up, the lawyer was careful not to cry malicious intent. “The defence does not claim that a group was organized to blame Gibril Massaquoi. Some witnesses did lie. But memories get confused with time. They might remember correctly but time, information from others, what the community wants to know, [the fact that] one wants to be part of the group, money – all this can play out. Personal, social relationships have an impact. In Africa, identity is more collective. That has to be taken into consideration.”

But Gummerus said GJRP director Hassan Bility - who testified that he was tortured by Massaquoi in a Liberian secret prison between late July and early August 2002 - was a party to the trial, and the main "witness finder" for the Finnish investigators was Bility's employee at GJRP. This "affects the credibility of the evidence", he told the court, and "the investigation is no longer reliable”.

"Witnesses were coached"

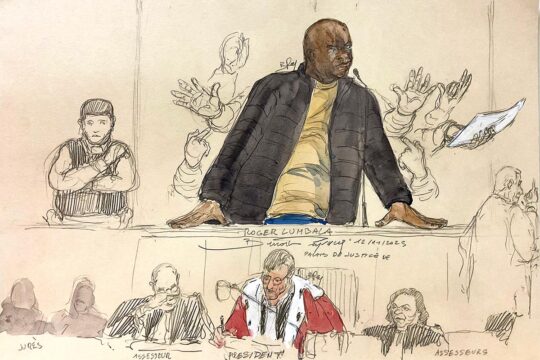

Massaquoi, in a black jacket and dark blue shirt, may have become a bit Finnish over time. For the few minutes he spoke one last time, at the end of the hearing, he did no more than object to a few facts put forward by the prosecutor. Certainly, there was more ardour in his words than in the court, but he did not try to play the tragic dimension of a man facing possible life imprisonment for crimes he says he did not commit. He was, however, less careful than his lawyer. "These witnesses were coached, compromised and fixed by the GJRP, by Hassan Bility," he said. "Why did 31 witnesses from the first batch change their timing?”

Prosecutor Laitinen called for life imprisonment, or a prison term of 15 to six years, depending on the charges retained by the court. The defence called for an acquittal. As the defence did not expressly request that Massaquoi be released pending the judgment, the judges decided to keep him in jail, reserving the right to reverse this decision before the verdict. They announced the judgment for April 29 at the latest.