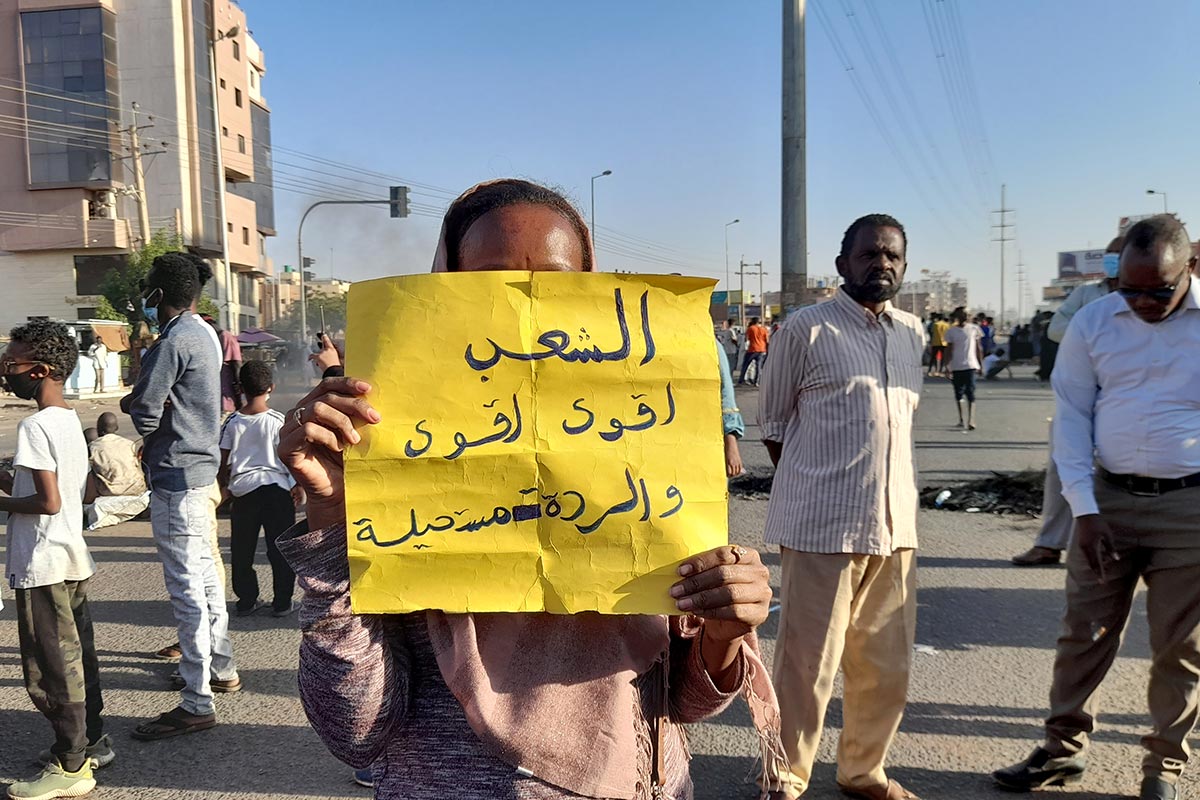

Three months after the October 25 coup, the junta in power in Khartoum is faced with revolt from a new sector of Sudanese society: the judiciary. While it is not all the judiciary, it is enough to worry the coup generals, if only because it shows that a significant number of state officials are resisting and rebelling. A statement issued on January 20 by 55 judges, including four from the Supreme Court, accused the military brass of being responsible for extra-judicial killings and "heinous violations against unarmed demonstrators”. They added that they would take the necessary measures to protect citizens, but did not specify.

They are supported by more than 220 prosecutors, who have announced that they will stop work from January 20. Their reason is again the security forces’ exactions against demonstrators, and they are calling for an end to the state of emergency in force since the coup.

Public statements by judges are very rare in Sudan, and are also risky for the signatories. Since the putsch, the military has dismissed civil servants appointed by the civilian government during the transition and has given key posts to men from the regime of deposed President Omar al-Bashir. This is being done quietly in the ministries considered strategic: finance and justice. All levels of the judiciary are involved, in the federal states as well as in the central administration.

A month after the coup, the Sovereign Council, the body that was supposed to oversee the democratic transition and which is now entirely controlled by the coup leaders, announced two important appointments: the chief of justice, who heads the judiciary, and the public prosecutor. Abdelaziz Fathal al-Rahman and Khalifa Ahmed Khalifa are well-known Islamists and al-Bashir's men. Both positions had previously remained vacant. General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, as head of the Sovereign Council, had blocked these appointments, refusing to endorse the names proposed by his civilian partners, the Forces of Freedom and Change (FFC) coalition.

“They are clamping down on everything," remarks bitterly a lawyer from Darfur who prefers to remain anonymous. “We find ourselves facing the same magistrates as under the regime of al-Bashir”.

Judicial reforms suspended

Justice, in the broad sense, has always been an obsession of the generals, who fear being one day dragged before national or international courts. They all served under al-Bashir, participating in abuses against the people and the repression of opponents. First among them is General Al-Burhan, former army chief of staff, who served in Darfur at the height of the war, notably as head of the border guards, which later evolved into the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) linked to the Janjaweed militia. Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, better known as Hemetti, who is the current head of the RSF and number two in the Sovereign Council, has similar fears.

As long as the top position in the Sovereign Council, the body overseeing the democratic transition, was held by a military officer - in this case, General Al-Burhan - the top brass could play for time. But according to the Constitutional Declaration of August 2019 at the beginning of the transition, this position was to revert to a civilian in November 2021.

The transfer of power did not take place. “Delaying the transfer of the Sovereign Council leadership to civilians is one of the major reasons for the coup," confirms legal expert Suliman Baldo, an advisor to the NGO Enough Project. “If it had taken place, legal issues would certainly have advanced: on the control of the economy; on the International Criminal Court; and on their alleged responsibility in the Khartoum massacre of June 3, 2019."

At dawn on June 3, 2019, security forces violently broke up a large sit-in that had been staged for two months by pro-democracy protesters in front of the army headquarters. Various security forces took part in the attack, including members of the RSF, Khartoum's auxiliaries during the war in Darfur. At least 127 people died, dozens disappeared, hundreds were injured, bodies were thrown into the Nile, and people were gang raped. The trauma is lasting and people are calling for justice.

Tightening a grip on the judiciary has not been difficult: after two years of democratic transition, reform of the judiciary was still in its infancy. “The State’s influence goes deep and many in all sectors of the judiciary owe their positions to their Islamist sympathies or their proximity to the NCP, Omar al-Bashir's party," explains Baldo. “Al-Burhan will therefore have no difficulty finding security and civilian cadres to manage the security of his regime and the state."

This is especially the case since, in the wake of last October's coup, General Al-Burhan changed the composition of the Sovereign Council, expelling the five members of the FFC coalition and replacing them with civilians under his thumb. The government was dissolved and the one he formed on January 20, with great difficulty, is composed of bureaucrats with no political stature or with ties to the former regime.

Investigation committees dissolved

Among the first decisions taken by the coup leaders was the dissolution of the committees investigating the actions of thAmong the first decisions taken by the putschists was the dissolution of certain committees, such as the one on the dismantling of the old regime. As for the committee on the events of June 3, chaired by lawyer Nabil Adib, it still exists but, according to one of its members, its action is "hampered by the lack of logistical support provided by the Prime Minister". "The generals were very worried about the conclusions of his report, which was due to come out soon," says Kholood Khair, executive director of the think tank Insight Partners in Khartoum.

The investigation was dragging on. Survivors and families of the victims, as well as some political parties, were accusing the government of obstruction. In fact, it was the military component of the government that was organizing a general policy of obstruction. "All those who worked in the committees set up to investigate the former regime faced obstacles of all kinds," says Mamoun Farouk, a lawyer and head of an anti-corruption committee. “For example, operating funds were never released. The Ministry of Finance gave the order, but the order was never signed at the demand, always verbal, of the military in the Sovereign Council. Weary of fighting, we paid for everything out of our own pockets, but that slowed down the procedures."

"Finding premises was also a challenge,” continues this former candidate for Attorney General. “We would find a house, a building, and the next day the owner would change his mind, or the Sovereign Council would pre-empt it for its own needs. This happened in particular to the June 3 investigation committee. They moved into the Sudan Airways training centre. Everyone knows that Sudan Airways does not have a single plane. And suddenly, after three months, the company needed its centre to train its stewards and pilots! Today, the buildings are still unoccupied..."

“We have completed some investigations," said Farouk. But the prosecutor's offices in Nyala [capital of South Darfur state] and those in Zalinjei [capital of Central Darfur] were burned. We don't know who set fire to them in these criminal incidents, we just know that it was armed men. As a result, no one has been brought to justice either for the crimes in Darfur or in the Nuba Mountains. This gives the perpetrators a sense of impunity, and the population the impression that the civilians in power did nothing. In fact, it is the military that has prevented the judicial process.”

Putting a brake on the ICC

The recent coup by the generals was thus just the culmination of two years of constant obstruction and pretence in all areas of justice, including international justice. In mid-December, a month and a half after the putsch, a delegation from the International Criminal Court (ICC) visited Khartoum. The objective was, once again, to discuss the transfer to The Hague of the three defendants claimed by the ICC and imprisoned in the Kober prison in Khartoum: former president al-Bashir, his former minister of defence Abdelrahim Hussein, and former minister of state for humanitarian affairs Ahmed Haroun. In a statement to journalists in North Darfur, Al-Hadi Idriss, a member of the Sovereign Council, nonetheless asserted unabashedly on December 14 that the Sudanese authorities remained committed "to handing over to the ICC those who have perpetuated crimes in Darfur, in accordance with what is enshrined in the Juba Peace Agreement," signed in October 2020 between the Khartoum government and a coalition of rebel movements, the Sudan Revolutionary Front.

The delegation led by prosecutor Karim Khan returned to the ICC empty-handed, and it is a safe bet that they will have to wait. "Real cooperation between the Sudanese authorities and the International Criminal Court had begun, even if it was incomplete because held back by the military component of the transition," says lawyer Salih Mahmoud Osman, winner of the 2019 Sakharov Prize.

In 2020, then-prosecutor Fatou Bensouda was allowed to visit Darfur twice and meet with victims. In August 2021, the Council of Ministers led by Abdallah Hamdok unanimously adopted a draft bill to ratify the ICC’s founding treaty, the Rome Statute, which was provided for in the Juba agreement. On his Facebook page, the Prime Minister welcomed the decision: "Justice and accountability are the solid foundations for the new Sudan, committed to the rule of law that we all want to build." The authorities then pledged to cooperate with the ICC and allow the opening of an office in Khartoum. “There are 18 of them here, they have visas and can investigate in Darfur," said Osman. “But transferring al-Bashir to The Hague is another story! The military has always blocked that.”

"I wonder if Al-Burhan ever intended to transfer to The Hague those who should be transferred. Omar al-Bashir was once a military man and head of the army. To hand him over to a justice system that is considered foreign would be considered treason by the military establishment," said Baldo. “During the two-year transition, al-Burhan's tactic was to publicly affirm his cooperation, but to effectively delay that same cooperation." In fact, General Al-Burhan never put the Rome Statute ratification project on the agenda. "The military deliberately delayed the process by procedural means," Baldo concluded.

ICC Prosecutor Khan stresses this in his report to the UN Security Council: according to the memorandum signed [in 2020] with the ICC and the Juba peace agreement, ICC investigators must have "full access to the territory of Sudan, including documents, archives, crime scenes, witnesses and other evidence relating to Darfur”. But they have never received a response to official requests for assistance. Since the coup, his teams have simply had no one to talk to. They face, he says, "additional difficulties in their investigative and cooperative activities due to the appointment of new government officials”.

"The military is right to be afraid"

In fact, everything has stopped. “No one talks about the ratification of the Rome Statute anymore, not even international organizations, because it is considered a political issue," said Mohamed Ibrahim Nkrumah, a human rights lawyer in Al-Fashir, capital of Sudan's Darfur province. “People are losing hope that the three defendants who are imprisoned in Sudan will be transferred and tried by the ICC. They need to see the men who ordered the crimes committed here in Darfur brought to international justice.”

The inhabitants of Abu Shouk displaced people’s camp, adjacent to the city, agree. “For the moment, only Ali Kushayb is going to be tried before the ICC," said a 24-year-old student and activist. “With the coordination of displaced people in Kalma camp, we have drawn up a list of 51 criminals that we want to see brought before international justice. Now we have to add others, like Hemetti, because the RSF is killing as we speak. And the Sudanese justice system will do nothing, it is even more politicized than before the coup."

For the violence has resumed, as American NGO Human Rights Watch warned in a December 15 press release. "A new wave of attacks on civilians in Darfur since mid-November 2021 highlights the urgent need for the United Nations to enhance its scrutiny of the restive region of Sudan,” it said. “A year after the withdrawal of the United Nations/African Union Hybrid Mission in Darfur (UNAMID), violence between armed groups, in some cases implicating state security forces, has been on the rise, with a devastating impact on civilians.”

In a bare room, sitting under a slogan "peace first" painted on one of the yellowish walls, the student talks about transitional justice with some of his friends. The concept is also raised during weekly discussions between young people, organized more or less discreetly depending on the security context. “Transitional justice is promised in the Juba peace agreement, and it is fundamental because it is the promise that crimes will be recognized and investigated. For us, the displaced, it means the end of fear," he says.

But nothing has been put in place. Yet this is not for lack of popular interest, says lawyer Nkrumah. "We are thinking about it a lot. Young people have set up discussion groups, either on social networks or on the ground, to explain that we must go beyond revenge. The elders have the crimes too much on their minds to accept without explanation that not all cases can be brought to justice, only the leaders can be brought before the courts, and that mediation and reconciliation will be necessary.”

It is curious to note that civil society is continuing its discussions on this while the military coup leaders are eating into the judiciary. "The issue of justice and responsibility cannot be forgotten. It is only temporarily suspended because of the circumstances," promises Osman, a calm and stubborn lawyer. “The military is right to be afraid of being accused of crimes in court one day.”