For more than a year, Belgium’s special commission on the colonial past has been working on its mission, which is to clarify the grey areas of colonial history and try to find out how the violence of colonization still creates suffering today. This mission has been welcomed everywhere. For the first time, a European state wants to face up to its entire colonial past, acknowledge its wrongs, apologize, make reparation, and compensate. However, after mandating ten experts to outline Belgium’s colonial history and suggest avenues for reconciliation, the commission does not seem to know where to start. While it still seems to be searching for a working method, two historians among the ten experts that wrote the initial report have expressed doubts publicly about the results of this parliamentary work.

Anne Wetsi Mpoma and Gillian Mathys participated on January 19 in a debate entitled "After colonization: seeking truth and reparation”. The event was organized by the Africa Museum in Tervuren, and moderated by writer David Van Reybrouck, author of "Congo: A History". It was also attended by Nanette Snoep, director of the Rautenstrauch-Joest-Museum in Germany.

For an hour and a half, the four specialists discussed the content of the experts' report, the conditions under which it was prepared, its weaknesses and its usefulness.

Need for a cultural community centre

Mathys, historian and researcher at Ghent University, thinks there wasn't enough time to produce a more complete and well-crafted report. "We never got to see the latest version of the report and the text is not very accessible to a wide audience," she says. "For historians, there is nothing new in this document. We've synthesized what's already there. But for the public, I think the element that stands out the most is the structural violence that existed during and after Leopold II", the Belgian king who personally acquired the Congo in 1885.

According to Mpoma, a member of Bamko, a centre for reflection and action on black racism, the most urgent recommendation for reconciliation and reparations should be creation of a cultural community centre, ideally in Brussels. "It would serve to organize meetings, debates, exhibitions, healing rituals, and house some of the despoiled heritage there," she says. "I am convinced, as an art historian, of the power of culture to change mentalities.”

Lack of access to archives

The two historians are especially sceptical about the commission's chances of achieving concrete results. "I'm a bit worried that it will stop when it comes to establishing responsibilities," says Mathys. "We need structural changes," says Mpoma. "The risk of nothing concrete coming out of this is more than real. Just the word 'consultation' [the commission asked the experts to consult four diaspora representatives in preparing their report] is patronizing," she says.

"I don't think this is a body that will lead to decolonization," says Mathys. "The commissioners want to do this exercise, but do they want to address structural change? This is an institution that is not designed to do that. Take, for example, the recommendations that were made after the Lumumba Commission [a parliamentary commission of inquiry, completed in 2001, into the assassination of Congolese Prime Minister Patrice Lumumba in 1961] which were never followed up. Let's hope that this will not happen again with this commission. To repair is also to change."

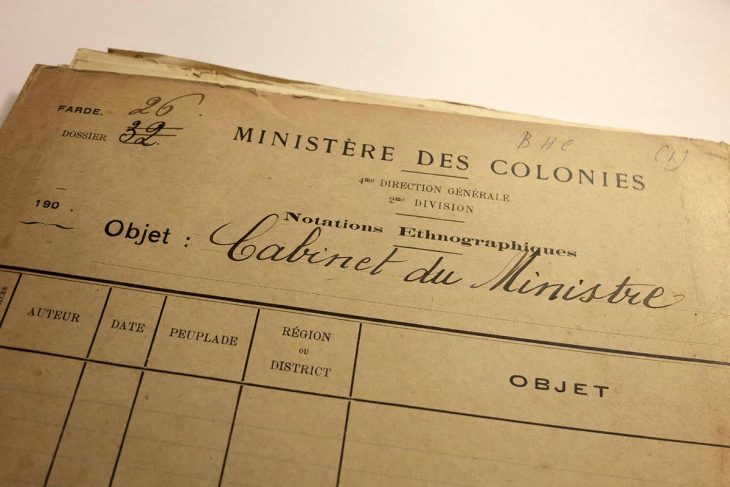

Another bad sign, according to the speakers, is the commission’s partial and conditional access to colonial archives. "Some of these archives are still classified. This is a problem for a commission that wants to shed light on the colonial past. Belgian researchers can obtain an exemption to have access to classified documents, but not Congolese, Rwandan or Burundian researchers," explained the participants.

Lack of concrete action

Since the submission of the experts' report in October, the special commission has made little progress. It has heard from some representatives of the diaspora and psychologist An Michiels on how to interview victims of serious crimes. It has just published an appeal "to the diaspora, civil society and interlocutors in Belgium, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Rwanda and Burundi" asking "on what issues they wish to be heard". It has also launched a call for two or three experts "for the continuation of its work". The "methodology" that it published, with an "overview of the planned work", is not well substantiated and does not allow for a concrete understanding of how its mission will unfold.

Given both doubts about whether it will achieve real change and expectations of concrete action with a clear vision, the commission on Belgium's colonial past runs the risk of tiring out the interest of the public and all those - researchers, members of the diaspora and victims of racism - who expect a lot from it.