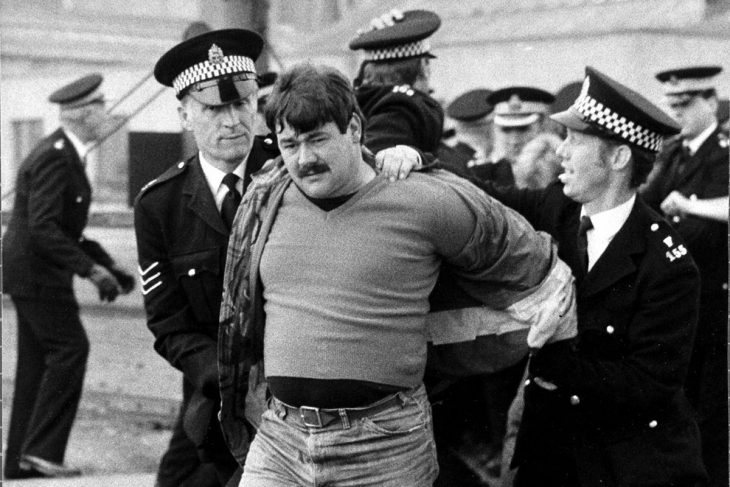

The British miners' strike lasted from 8 March 1984 to 3 March 1985. The violence of clashes - which led some commentators to speak of a "civil war" - caused 11 deaths and more than 7,000 injuries. It was a protest against the closure of 20 mines and the loss of 20,000 jobs. Nearly 140,000 miners followed the strike. More than 11,000 of them were arrested by the police and 5,653 prosecuted. Two hundred were imprisoned and more than a thousand were fired. It was a massive, extremely harsh conflict, which ended in the total defeat of the miners and which remains vivid in the political and social memory of Britain.

As we previously recounted, more than 30 years later, in June 2018, the Scottish government's secretary of state for justice, Michael Matheson, said he was "determined that the Scottish Government should do what it can to do right by those affected by the dispute". In his statement, Matheson stressed the continuing trauma of silence and a sense of injustice. Supported by the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM)’s president in Scotland Nicky Wilson, he announced the establishment of an independent commission of inquiry to "investigate the impact of policing on affected communities in Scotland" during this period. The commission's work culminated in a final report in October 2020 and, a year later, the submission by the Scottish government of a bill to pardon miners arrested and convicted during the 1984-85 strikes.

A transitional justice approach

Remarkably, the commission's inquiry that led to introduction of the bill was part of a global and inclusive approach, which made victims' hearings a preferred mechanism for seeking the truth. Its stated intention was to work over a fairly long period (June 2018-October 2020) and involve a large number of people and institutions, allowing for the gradual emergence of a narrative testifying to multiple memories.

Especially to be highlighted is that it organized a certain number of public meetings in various places symbolic of the strike. Both in terms of their importance and their content, these public meetings were part of a logic of transitional justice - similar to the mobile hearings of certain truth commissions.

In Scotland, these meetings were held in eight locations and were attended by 167 people. “Meetings generally lasted for three hours, allowing everyone who wished to speak to be heard,” says the commission. “Attendance at some meetings was quite small but, at those meetings, we were able to have more in-depth discussion with those who attended.”

The minutes of these meetings show the depth and long-lasting nature of the trauma. It appears the years that have passed have not put an end to the suffering, and that the effects of the strike are still being felt in the communities. This suffering has its roots in the repression but also its longer-term consequences: “We heard powerful and moving testimony from individuals and their families who had been very badly affected by the strike, especially those who were arrested, charged, prosecuted, convicted and sentenced,” the commission writes.

And it is the principle of being able to express this "felt" truth that was appreciated by those concerned. “It is worth noting," the commission continues, "that at all of our meetings, speakers were generally keen to acknowledge their appreciation that the Scottish Government had set up this review. While many wanted more, in particular those who continue to campaign for a full public inquiry at UK level, and some queried the limits of our Terms of Reference, those who spoke said that they were glad to be heard and listened to, for what seemed to many to be the first time.”

Wide social trauma

Both the intentions of the Scottish government in setting up the commission and these reports reflect the fact that there has been considerable social trauma. "Although more than three decades have passed since the main miners' dispute, the scars from the experience still run deep," said the Scottish justice minister in a speech when he received the report and introduced the bill. "In some areas of the country most heavily impacted, the sense of having been hurt and wronged remains corrosive and alienating. That is true of many who were caught up in the dispute and aftermath. Those who were employed in the mining industry at the time, of course, but also wider families and communities. The miners' strike was also a difficult period for the police, with many individual officers finding themselves in extremely challenging situations, and police and community relationships coming under unprecedented strain.”

Confronted with a global form of social trauma, the commission set out to incorporate truth seeking mechanisms. Throughout their work, commission members noted two characteristics emerging from the debates and exchanges that bring this experience closer to those of truth and reconciliation commissions.

First of all, expressions of individual trauma, whose intensity and complexity shows states of mind and the impact of the violence. This was notably the case during face-to-face meetings between miners and former police officers, allowing the commission to evaluate “the strength of feeling and some of the subtlety of impacts and impressions not always captured in written submissions".

There was also expression of a collective traumatic reality that goes beyond individuals to affect entire communities, perpetuating the divisions and ruptures born of the strike and its repression. “The meetings confirmed,” says the interim report, “that, as a result, strong feelings persist on the subject of the 1984/85 strike and its policing. [ … ] We have been conscious of the fact that the public meetings in mining communities were not necessarily conducive for retired police officers to share their experience and recollections but were keen to try to have some further face-to-face meetings with retired officers."

The limits of rehabilitation

In response to the findings of the commission of inquiry, the Scottish government has developed a mechanism for redress. However, this willingness seems to reflect a paradox: even though the principle of need for reparation was amply confirmed in the report submitted in 2020, the reparation granted appears to be relatively small in relation to the extent and complexity of the harm suffered.

In March 2021, the government began a public consultation to establish the appropriate criteria for a law on pardons. The consultation received 377 responses from individuals and 13 organizations, which demonstrated clear support for the rehabilitation of miners. The government then introduced a bill in parliament that proposes to grant "a collective and automatic pardon" to former miners convicted of the following offences related to the 1984-1985 miners' strike: breach of the peace; breach of bail conditions; assault or resisting, molesting and obstructing a police officer or a person assisting a police officer in the performance of his or her duties. The offence must have been committed while the miner was participating in or traveling to or from a picket line, demonstration or similar pro-strike rally.

However, the pardon granted in the current bill does not provide for any effect on the conviction or sentence. It does not give rise to any rights for the person benefiting from it, nor does it call into question the responsibility of the institution that handed down the conviction. This is despite other possibilities, such as the conviction being overturned and compensation granted.

A central objective: reconciliation

In addition, the financial harm suffered by convicted miners is not be taken into account either. This includes loss of their jobs, the cost of legal proceedings, fines to be paid, loss of years of wages, etc. For the moment, it appears that this injustice will not be remedied by the law. Quantitatively, the scope of the law seems uncertain: according to the note accompanying the draft, the miners eligible for pardons could represent a group of 200 to 400 people, but no study has yet established with certainty the exact number.

Perhaps this is why the minister emphasized that the pardons for former miners are done in a "spirit of reconciliation" and symbolize “our desire as a country for truth and reconciliation”, as stated in the bill. For while it was indeed a question of getting to the "truth" about the law and order violations during the strike, the commission's mission was envisioned from the start as a "reconciliation" project.

The policy memorandum accompanying the bill explains that the pardon is intended to "remove the stigma of any associated convictions”. It emphasizes that it “presents an opportunity now to bring reconciliation between those who were upholding the law in circumstances of a scale which they had never encountered before - and to those who were fighting to protect their jobs, their way of life, and their communities”. The pardons as envisioned in the bill thus aim, the memorandum argues, to "encourage reconciliation, but without suggesting that the law itself was at fault, or was applied in a systemically discriminatory manner”.

The bill is currently before the Equalities, Human Rights and Civil Justice Committee. Its review is expected to conclude in June 2022. Despite its limitations, this process appears promising for restoring social peace and reconciling the population after 40 years of continued injustice.

President of the Francophone Institute for Justice and Democracy, Jean-Pierre Massias is a law professor specializing in democratic transition processes and transitional justice mechanisms. He also directs several field projects, notably in the Central African Republic and the Democratic Republic of Congo, many of which are devoted to the treatment of wartime rape and conducted in collaboration with the Dr. Mukwege, Panzi and Pierre Fabre Foundations.

Niki Siampakou holds a doctorate in public law from the University of Aix-Marseille and is in charge of research and training at the Francophone Institute for Justice and Democracy - Institut Louis Joinet. A visiting scholar at New York University and Amsterdam University, her research focuses on international criminal law, international human rights law and critical theories of international law.