A week after his electoral debacle in Senegal's local elections, President Macky Sall was able to raise his head on the international stage. The day before the Lions' first victory in the African Cup of Nations final, he took over as chairperson of the African Union for a year. In his inaugural speech, delivered on February 5 in Addis Ababa, the issue of restitution came at the end, after the many security and economic challenges that await him. But his words were strong and determined.

“The restitution of our stolen heritage will remain at the heart of our agenda, because it is an integral part of our civilizational identity; it is what connects us to our past and is part of the legacy that we must bequeath to future generations," said Sall. “The Africa that we want to build cannot ignore its cultural heritage. Time cannot erase our collective memory. (...) We say yes to giving and receiving through fruitful dialogue of cultures and civilizations; but no to injunctions that would dictate our choices and our behaviour.”

These words echo what President Sall said on December 6, 2018, during the inauguration of the Museum of Black Civilizations (MCN) in Dakar. He was speaking before an audience of Senegalese cultural actors and intellectuals as well as diplomats and the special envoy of Xi Jinping, the president of China, which financed its construction. He paid a strong tribute to pan-Africanist and anti-colonialist leaders, and to Senegal’s first post-independence president Léopold Sédar Senghor. A few days after the Sarr/Savoy report on the restitution of African heritage was published in France, Senegal's former colonial power, Sall firmly reminded French President Emmanuel Macron of his promises a year earlier during a speech in Ouagadougou. “We have no other choice but to accept the invitation of poet-president Léopold Sédar Senghor and walk together to the place of giving and receiving, a prelude to the civilization of the universal, a symbiosis of all cultures and civilizations,” said Sall, keen to stress his pan-Africanism.

Senghor's pan-Africanist dream

The visitor entering the imposing MCN museum shaped like a large amphitheatre first comes face to face with a reproduction of Toumaï, a 7 million year old skull discovered in a desert in Chad, "our common ancestor". This surprising introduction reminds us that Africa is the cradle of humanity.

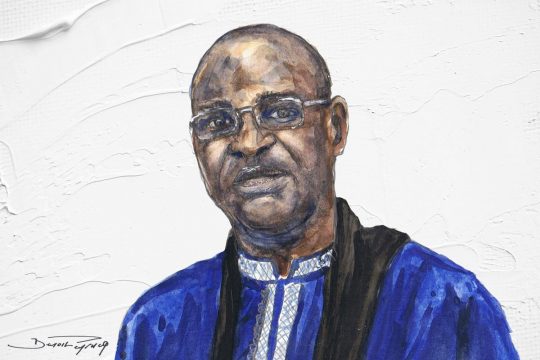

"This museum was conceived from the start as a continuous creation of humanity," says Hamady Bocoum, the director of the MCN, who is seen here as the key man in restitution of cultural objects stolen during the colonial period. Bocoum recalls that it was Senghor himself who wanted to create a "negro-African" museum after the first Festival of Black Arts in 1966. Senghor left the presidency in 1980, his dream unfulfilled. Twenty yearslater, this great pan-Africanist project was resurrected by President Abdoulaye Wade. "Senghor dreamed it, Wade wanted it and Macky Sall realized it," summarizes Bocoum. "It was in 2010 that we obtained the financing from the People's Republic of China, then there was a political change [at the head of the state, in 2012], and the work began in 2013." Bocoum, then director of the IFAN Museum of African Arts founded in colonial times by Theodore Monod, followed and supported the work, and says he was then "naturally" appointed to be its director.

“A museum of insubordination”

The MCN is intended to break fundamentally with the dusty old IFAN museum and its colonial architecture - called neo-Sudanese when it was built in the 1930s – which preserves in Dakar some ten thousand objects "devoted to the arts and traditions of West Africa". “The Museum of Black Civilizations is not an ethnographic museum, it is not an anthropological museum, it is not a chromatic museum - it is a museum of insubordination," says Bocoum. “We don't want to be like anyone else, we're going to do our own thing. That will be our choice."

The museum has no permanent collection. It is starting from scratch and in fact has no collections, although Bocoum says it is planned that objects returned to Senegal be kept there. The Museum of Black Civilizations," he says, "is ready to receive any African object, or even from the rest of the world. We see ourselves as having a universal vocation. We are ready to house the Mona Lisa. In two months, we will exhibit Picasso and last year we exhibited Leonardo da Vinci. I say this seriously. This is not the museum of Black people, it is really the museum of Black people in global times. And as Africa is the cradle of humanity, this museum is open to the world. It speaks of everything. One floor of the museum is dedicated to contemporary artists.

Certainly the objects seized during the colonial era were seized in a context of subordination and must be returned, says Bocoum, who was in November appointed coordinator of the Senegal Special Commission on Restitution. But he nuances his argument. "Restitution is not a fundamental issue, even if it is important. What is in the West must be recovered. But it should not be considered essential. When we say that 90% of African cultural heritage is abroad, it is not true. We don’t know even 1 % of African heritage, all that archaeologists are starting to uncover, all the contemporary production. To say 'full speed ahead for restitution' would be delusion, we need to step back and analyse. We need to work with the colleagues in the museums, who are responsible, qualified people and then recover what seems to us the most important.”

A recent meeting took place in Dakar, he explains, with the Parisian Quai Branly Museum, which is working with other African museums on an ambitious "provenance research" programme on 3,500 objects brought back to France in 1933 by the famous Dakar-Djibouti expedition. This expedition that crossed 18 countries is considered the founder of the so-called "ethnographic" collection method, which brought 70,000 objects from the African continent to the Musée Branly. This research, according to the Musée Branly, is likely to take several years and could lead to an exhibition, with all the African partners, in 2025.

Inventories, meetings and commissions

So, after the Ouagadougou speech in 2017 and the start of restitution requests, have we already entered a period of waiting, diplomacy and research? In fact, in Senegal, there has been no other official restitution request since the symbolic handing over of the sword of El Hadj Oumar Tall, which can be seen at the MCN. In France, requests received by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in 2019 come from seven countries: Senegal and Benin, whose requests have been followed by restitutions; Mali, Côte d'Ivoire, Chad, Ethiopia, and Madagascar, whose requests remain to be followed up. There have been no further requests since then, according to our sources. On the Senegalese side, two upcoming missions are planned: one to the museum in Le Havre, for jewellery and other pieces claimed by the descendants of Oumar Tall (who are planning a museum in a mosque under construction); and the other to the Musée Branly, to identify the pieces belonging to Senegal. More requests could therefore follow.

Several people we met in Dakar expressed regret that the pace of restitutions has been suspended, owing to Covid-19. After the headline-catching announcements, it was time for inventories, coordination and negotiations. In Senegal, although everything began in 2019, it was not until the end of 2021 that the work of the Special Commission really started. "Since 2021, I have been associated with the work of harmonizing internally and at the African level,” says Fatima Fall, museum curator in Saint-Louis and Senegalese president of the International Council of Museums. “We need to involve the countries of the sub-region in the inventory of our intangible heritage. It is a question of knowing to whom we will return what, how we will return it, who will coordinate between the countries of Africa.”

Meanwhile, consultations have taken place at the level of the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) and the African Union (AU), "which should lead to a common position of African states in January 2023", adds Senegalese lawyer Ibrahima Kane, who is following this issue for the Open Society Initiative for West Africa’s project on restitution. The NGO had a fund of 15 million dollars for the project at the end of 2019. Again, the pandemic has slowed everything down, says Kane, and only five million has been spent so far to support the design of an action plan by ECOWAS and the AU; to help Benin City in Nigeria lobby the German authorities for restitution of its bronzes; organize conferences and try to mobilize civil society on the issue. "What is still missing is an angle of attack, an African Union common position," says Kane.

“De-Berlinizing” restitution requests

“These thefts were perpetrated during the colonial period, when the current states did not exist," he continues. “The kingdom of Benin, for example, was a kingdom that extended from Nigeria to present-day Togo. If we are to make big demands for restitution, who should make them?” At the African Union, he says, nothing is settled yet. "Within the framework of a common position, we want to 'de-Berlinize' this issue of restitution, we must organize ourselves among Africans." This is the leitmotiv at the heart of the debate on restitutions, a reference to the division of Africa between colonial powers, ratified at the Berlin Conference in 1885.

Senegal is not the only one to take a stand on the issue, Kane continues. "Algeria has launched the idea of a great African museum. There is a pharaonic museum that Egypt is building. In South Africa, museum techniques are very advanced. But all this must be coordinated at the level of the African Union.”

"Cultural communities do not correspond with administrative boundaries," also notes Massamba Gueye, a teacher, researcher and adviser on culture and heritage for Senegal’s presidency. "The position of President Sall is that everything must return, but that this issue should not lead to diplomatic breakdowns,” he explains. “This issue must be carried by the African Union because when colonization and slavery began, these countries did not exist. We must say what we want and we must not be the echo of the will of the West. So far, this is a weakness for Africa because it has not yet built a coherent discourse."

Gueye points to the lack of leadership of heads of state, who have not seized the window of opportunity opened by Macron. "For as long as we have been talking about it, if the African Union took this matter seriously, we would have had a written and signed request on the table of the United Nations with clear deadlines and terms of reference. After the Ouagadougou speech, Africa did not provide the necessary response. Africa had the opportunity to demand clear, precise and fixed terms of reference. It is not yet too late but in a way yes, we missed the boat.”