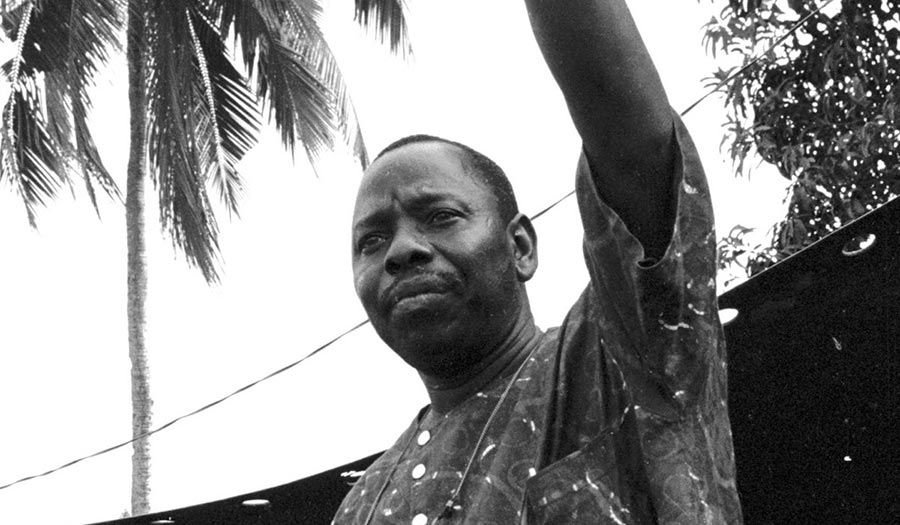

It was almost thirty years ago when nine men from Ogoniland in the southeast of Nigeria were hanged for their alleged responsibility for the murders of four leaders from their own community. They became known as the ‘Ogoni 9’. Among them was Nigerian writer and activist Ken Saro-Wiwa. Their case became a world symbol of the brutal dictatorship of Nigeria’s military leader Sani Abacha, and of the environmental destruction and disregard for local communities by the multinational petroleum industry, among them Royal Dutch Shell.

The 1995 trial was seen by observers at the time as flawed – the men’s lawyers quit part way through in protest at what they considered a rigged process. In 2017 the reverberations of this original trial made their way to a court in The Netherlands. The case at the district court of The Hague was brought by Esther Kiobel, widow of Barinem Kiobel, one of the ‘Ogoni 9’, alongside three of the other widows. They have been supported by human rights pressure group Amnesty International over many years in efforts to have Shell be held responsible for what happened to their husbands. However, on March 23 judges decided that shaky witness’ recollections made it impossible to hold the oil company Shell liable for the men’s deaths.

Witness’ testimonies, 30 years later

When Saro-Wiwa was put on trial in May 1994, it was headline news. He had made a name campaigning against the pollution of his homeland by oil production. He targeted the biggest company operating in Nigeria, Shell, which had a local subsidiary SPDC. He allied with environmental movements worldwide to call attention to the devastation oil had brought his community in the Niger Delta. Patches of oil soaked into the ground destroying traditional agriculture. Gas flares from the pipelines lit the night skies right next to villages. People lacked access to health facilities, roads, schools. Saro-Wiwa’s Movement for the Survival of the Ogoni People (MOSOP) gathered the pent-up anger of the youth and gave them hope their conditions would change. Some in the community, especially those who had benefited from close relations with the oil companies and with the authorities objected. At the trial in Port Harcourt there were conflicting accounts of how the local leaders had died and whether MOSOP, Saro-Wiwa, or any of the other men on trial bore responsibility for the deaths.

There was international outrage after the ‘Ogoni 9’ were found guilty and hanged. Shell caught much of the flack; to do business in Nigeria they had to be close to the military authorities, but precisely how dirty their hands were was hotly debated.

At the court in The Hague, judges have tried to pick their way through closed-door testimonies of people who had said they believed Shell had been involved - via bribery - in fixing the testimony against Saro-Wiwa and the others. “This is the core of the issue”, says Lucas Roorda of Utrecht University. “It’s something that happened 30 years ago in a very opaque situation. Relying on witness statements would be difficult one year later and is exponentially more difficult 30 years after the facts.”

Imbalanced access to information

The judges concluded that the recollections were too unclear for them to be sure and decided that Esther Kiobel and her fellow widows could not prove their case that Shell should be held responsible for the human rights abuses they had suffered. “They didn’t even get to that question”, says Roorda, “it was all about content of the witness statements.”

In 2019 the judges had already rejected a range of claims from the plaintiffs, while saying the case could go ahead. Again, this time the judges turned down the repeated arguments from the widows’ lawyers that Shell failed to use its “influence – publicly or otherwise – to urge the Nigerian government to hold a fair trial and show clemency to the Ogoni 9”, saying “this accusation lacks any factual basis”. Nor did the court accept evidence that Shell had promised “to intervene in the trial on the condition that MOSOP would cease its resistance”.

Roorda says you “need to read these decisions together” because in that first decision, the judges “already boxed and dismissed much of the case” by rejecting the claimants’ disclosure requests for more evidence from Shell’s records. “There’s a big imbalance in the information situation between claimants and companies, that’s what this case points to most of all,” he says. While “we knew it, this result really makes it clear.”

The limits of a civil case

Speaking to journalists after the hearing on March 23 Esther Kiobel said, “what matters is that our voice has been heard”. Her lawyers said they would consider appealing and would want to reassess the 2019 “wrong” decision to exclude some evidence.

“There are some good chances” they can appeal, says Roorda. “I think there are ample grounds to do it”. He particularly points to the way the judges assessed the evidence that seemed to make it very hard for the claimants to prove their case. The judges did not make the standard they used explicit, he notes, but the way the judgment reads is as if they used “beyond reasonable doubt” as their yardstick; “it reads is like a criminal investigation,” he says, rather than the “balance of probabilities” that would usually be seen in a civil case.

Seun Bakare from Amnesty International was disappointed by the verdict especially by how long the victims have had to wait. “Human memory is feeble. Even victims cannot preserve evidence as they want. Courts should not delay.”

What happened was that the widows had previously tried for many years to press their suit against Shell through the US courts, but that was rejected by the Supreme Court in 2013, because there was not sufficient linkage to the US. It was only after that they turned to the Netherlands as the home country of Shell.

Roorda stresses it’s important to realise that civil courts do not conduct investigations and are dependent on what parties bring to them. In this case it was difficult to assess how the court dealt with the evidence because so much was confidential, he says. “Normally this kind of court deals with car crashes,” he notes. “Could the court do more? Maybe. But what can you reasonably expect?”