When we published an article last year with sociolegal scholar Lorena Vega, an editor drew our attention to the “truly shocking number” that 80,000 forced disappearances is “applied only to Colombia.” His disbelief was such that he asked me to clarify this number in a separate e-mail.

Numbers are often thought to hide the horror of armed conflicts by dehumanizing the victims. Given the nature and magnitude of the crime of forced disappearance, civil society initiatives attempt to give victims their individuality back and families a means to memorialize them through embroidery, installations, documentaries, or transmedia projects. Other work like the one carried out by Equitas in Colombia or Menos Días Aquí in Mexico reflect citizens’ counter-forensic power in the face of state incapacity or willful denial of this crime.

At the same time, our understanding of both large-scale human rights violations and the transitional justice measures adopted to deal with them has been constructed through victims’ registers. This is one reason why the numbers of forced disappearance in the Colombian armed conflict matter.

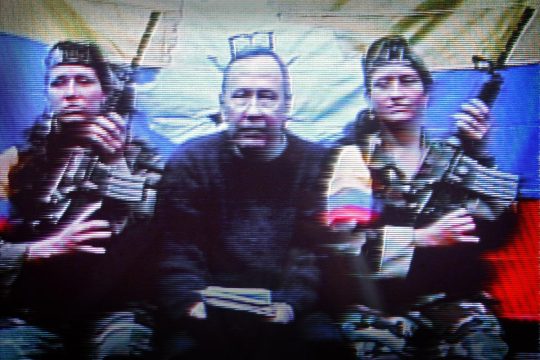

By comparison to Peru or Guatemala, the Colombian registers of conflict-related harms present two particularities. First, despite the 2016 peace agreement with the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), hostilities between the government and a number of non-state armed groups, including FARC dissidents, continue, and new victimizing acts are still being recorded in nearly all categories of existing registers. Second, there is still widespread disagreement about the start date of the country’s armed conflict. This explains how, although they are both institutions in the transitional justice system stemming from the same peace deal, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) uses the year 1958 and the Unit for the Search of Persons Deemed Missing (UBPD) mainly uses 1948.

Civil Society Records: Night and Fog

The first known Colombian register of human rights violations that included forced disappearance originates in the work of civil society. Father Javier Giraldo, a Jesuit priest and key figure in the human rights movement who helped found the first organization for relatives of victims of forced disappearance, also created the Data Bank of Human Rights, International Humanitarian Law and Political Violence together with Father Alejandro Angulo. When they started their data collection, which consisted primarily of newspaper clippings and testimonies, in the late 1980s, they modelled it on similar efforts in the Southern Cone, primarily Argentina and Chile, during the military regimes there. By mid-1990, they released a magazine named Night and Fog – in honour of Alain Resnais’s famous documentary on the Holocaust – to give the database a public medium. The first issue contained data on extrajudicial killings, torture, kidnapping, and forced disappearances by both state and non-state actors as well as unidentified perpetrators that took place between July and August of 1996. The same year, another civil society organization, the Consultancy for Human Rights and Displacement (CODHES), created and released its database tracking forced displacement with estimates going back to 1985. Since forced disappearance has often been used by right-wing paramilitary actors and drug traffickers as a terror tactic to induce forced displacement and facilitate land accumulation, the combination of these two databases gave Colombians insight into the true magnitude of conflict-related harms for the first time.

The first state-sanctioned register

Largely owing to the social and legal mobilization of ASFADDES, the relatives’ organization established with the help of Father Giraldo, the crime of forced disappearance was typified through a law in 2000 following the ban introduced in Colombia’s 1991 Constitution. While the Attorney General’s Office certainly was aware of cases of forced disappearances in the interim, this legislation created the first nationwide and state-sanctioned Registro Nacional de Desaparecidos (RND, or National Registry of Disappeared Persons) and tasked the National Institute for Legal Medicine and Forensic Sciences with coordinating it. According to a 2005 decree, the main purpose of this register is to assist the identification of the human remains, direct the search for those reported missing and facilitate the follow-up of the cases. It should be noted that while the 2000 law does speak about armed actors and the security forces as possible perpetrators, this register is not strictly speaking circumscribed to the armed conflict. Since the government of Colombia only recognized the existence of the armed conflict a decade later, this register continues to function today as general missing persons register.

Since 2004, the RND also includes findings under the ordinary criminal justice system as well as the special transitional justice proceedings under a 2005 law that demobilized the pro-state paramilitary groups. It refers upwards of 33,000 victims of alleged forced disappearance and little over 134,000 persons classified with ‘no information’ since 1930. Simultaneously the ordinary criminal justice system registers around 102,000 victims between 1968 and 2021. Given the different start dates, the dubious classification of such a high number of victims and the lack of a direct link with the armed conflict, civil society organizations do not regard these as trustworthy records of victims of forced disappearance.

Reparations’ Registers

Victims of forced disappearance entered the field of vision of the state again for the purposes of redress. Since the drawn-out prosecution of paramilitaries demobilizing under 2005 legislation was delaying the reparation, the state established its first conflict-related administrative reparations programme. A 2008 decree created a registration procedure for beneficiaries that included victims of forced disappearance. This register, however, left out the victims of armed actors not undergoing demobilizations, such as state agents and Leftist insurgent groups, by design due to the demobilization nature of the law preceding it.

The current Single Registry of Victims (RUV, Registro Único de Víctimas) emerging out of a 2011 law known as the Victims and Land Restitution Bill registers all victims of forced disappearance, regardless of whether or not their perpetrator is identified, undergoing demobilization, or their trial has finished. The limitation that it imposes with respect to receiving compensation is that the violation should have taken place after 1 January 1985. Given that the purpose of the 2008 and 2011 registers is specifically reparations, they bring a different focus on the problem. The RUV currently contains little over 50,500 direct victims and 138,000 indirect victims. The former number refers to individuals who fulfil the conditions of the 2000 law for forced disappearance and are recognized as conflict-related victims by the relevant state agency, and the latter number to their surviving relatives who are due reparations.

Two more registers

The Observatory of Memory and Conflict is the broadest information source on the internal armed conflict to date. Its advantage is that it integrates both state-sanctioned sources and civil society ones, including testimonies, and it goes back to 1958. It is part of the National Centre for History Memory, a government institution created in 2011, but unlike the Single Registry (RUV) set up by the same legislation, it does not have a restorative purpose. Rather, it seeks historic clarification and recognition. Launched in 2018, this Register speaks of roughly 80,000 direct victims of forced disappearance between 1958 and 2022.

According to a 2017 decree, the work of the Unit for the Search of Persons Deemed Missing (UBPD) is focused on people “presumed missing in the context and on account of the armed conflict.” Following the peace agreement with the FARC, this includes civilians as well as (presumed) former combatants reported missing as the result of kidnapping, forced disappearance, forced recruitment or in hostilities that took place before 1 December 2016. The UBPD is an extra-judicial and humanitarian body. Since its work is not limited to the criminal typology of forced disappearance, its register builds on as well as feeds into the RND without fully overlapping. While data from the register of the UBPD shows it goes back to 1921 and currently contains upwards of 99,000 victims, the UBPD director Luz Marina Monzón has referred to 120,000 disappeared and 1948 as the start date for the conflict.

Trust and transparency

Forced disappearance is a state crime par excellence. While state agents may not have been directly involved, as in the “false positives” (extrajudicial executions) case currently before the transitional justice tribunal known as JEP, it is ultimately state agents that are responsible for the location, identification and return of the remains of the victims to their families as well as any legal action necessary.

When I first started to research forced disappearance in Colombia, the relatives of the victims told me that when they first approached the Latin-American Federation of Associations of Relatives of Disappeared-Detainees (FEDEFAM) in the mid-1980s, the organization had difficulty to understand the crime outside of the context of the Southern Cone military regimes. It was simply unimaginable to them that this would be happening in one of the purportedly most stable democracies of Latin America, as Colombia was referred to despite the decades’ long armed conflict.

These registers, as confusing as they may appear, give an impression of the magnitude of the problem. Their discrepancies in terms of numbers, that recently caused alarm with the UN Committee on Forced Disappearance, is also an issue of the characterization of victims and rights’ enforcement. Relatives, who carried the burden of fighting against impunity from the moment of documentation, have persistently mobilized legally and socially to change social and political imaginaries on this crime. Where some states have taken to distorting numbers as a means to deny this violation, inducing a second disappearance, public clarification of both registers and numbers in Colombia, as asked by the UN Committee on Forced Disappearance, would reduce historic mistrust in the state by increasing transparency.

Adriana Rudling, who holds a PhD in politics from the University of Sheffield, UK, is a post-doctoral researcher at the Chr Michelsen Institute, Bergen, Norway and a post-doctoral visiting fellow at the Instituto Pensar, Bogota, Colombia. Her research interests centre on the interactions between victims of massive and systematic human rights violations and the mechanisms and measures adopted to deal with the violent past.