“I had a lot of pain last night,” Eshetu Alemu coughed, “but I will try to be present during the entire day.” The 68-year-old Ethiopian-Dutchman has terminal lung cancer and he attended his trial via video link from prison. A convicted war criminal, he wants his entire 2017 life sentence – for 75 murders, 6 cases of torture and 320 arbitrary detentions in cruel and degrading circumstances between February and December 1978 in the cities of Debre Markos and Metekel – quashed. He “regrets” that all these things happened. But he maintains he was never at any crime scene.

On 19 April, Alemu heard his Dutch lawyer plead his case. “We have to separate facts from fiction,” began Sander Arts. He claimed all testimonial evidence was riddled with hearsay, collusion and inconsistencies. The witnesses mistook the identity of his client, Arts argued: “There were are least three Eshetu Alemus at the time!” Moreover, he added, the many documents in the gigantic casefile “are contaminated”. He questioned how Alemu’s signature – if even his – had landed on death reports. And he concluded by contending that Alemu himself was a victim of a deadly Communist regime which had dragged Ethiopia into the abyss.

From poetry to ‘Avenger’

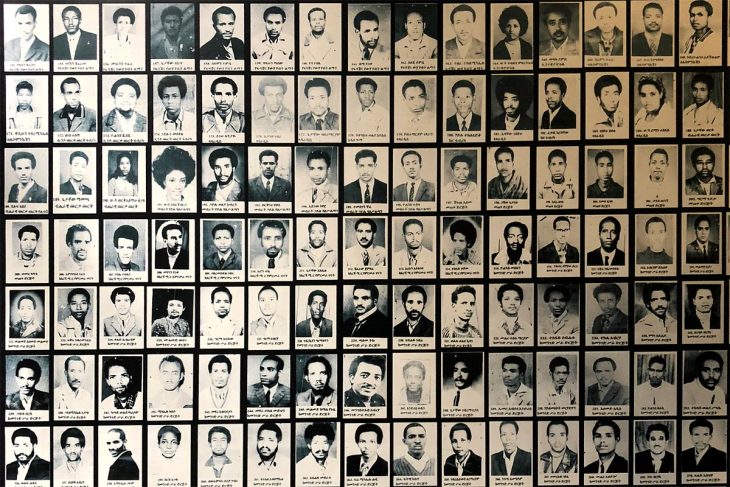

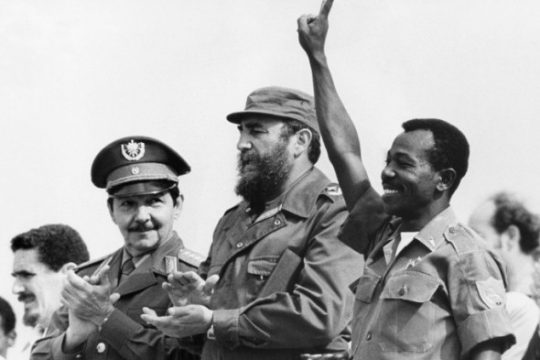

Alemu was the 49th member of the Derg, a military cabal that took power after the 1974 revolution and dethronement of Africa’s last emperor, Haile Selassie. In March 1977, the junta’s leader, Mengistu Haile Mariam, proclaimed the Qey Shibir (the “Red Terror”). The campaign was designed to “crush” any suspected supporter of the junta’s main socialist rival, the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Party (EPRP). Kebele militia and police conducted raids in the cities. At so-called “exposure meetings”, students, teachers and workers were forced to confess they were counterrevolutionaries. Makeshift prisons swelled. Corpses were displayed on Addis Ababa’s streets.

A former private like his father, who had fought against the Italian fascist invaders in the mid-1930s, Alemu joined the student movement and became a passionate disciple of Mengistu. He liked poetry, drama and theatre, but found most solace in Karl Marx’s writings. A talented orator, Alemu described himself as a propagandist and educator. At the Red Terror’s peak however, he was assistant to Melaku Teferra, a ruthless administrator – known as “the butcher” – in Gondar province. And from 1978, Alemu was sent to Gojam province as “chairman of the Coordinating Council of the Revolutionary Campaign” – a fact he admits.

Witnesses remembered Alemu as a young viceroy, who ran and ordered anti-revolutionary operations and “measures” from an old palace in Gojam’s administrative capital and university town, Debre Markos. Although armed conflict raged elsewhere in the country – Tigray, Eritrea, Ogaden, Oromia –, Gojam was mainly the theatre of political persecution of EPRP associates. Some 321 people, mostly students – some just 12-years-old – were arbitrarily detained in late February 1978. Many ended up in a camp called Demmelash (“Avenger”).

Conditions in Demmelash’s unsanitary “dark rooms” were miserable. Unpalatable food, filthy water and no medicine caused diseases. Prisoners were shackled together during sleepless nights; many were whipped with spoons; others were suspended in the air, with their hands and feet tied together. And on at least one night, on 14 August 1978, 70 prisoners were taken to the prison’s church, where they were forced to kneel, their necks tied together with ropes and strangled. Some still alive, they were buried in a mass grave dug by non-political prisoners.

‘Judge and executioner’

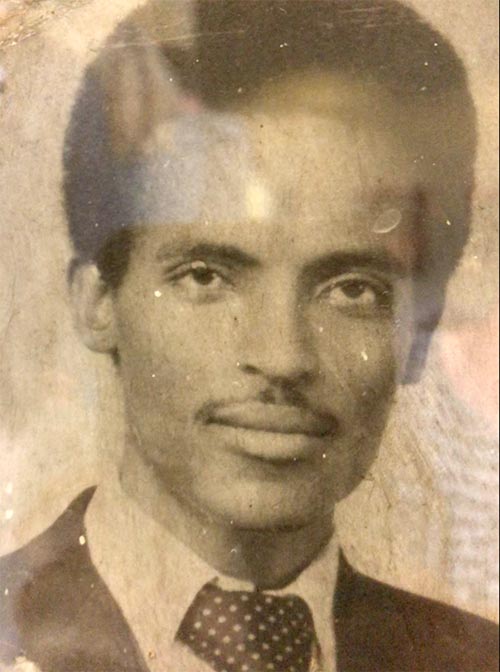

Alemu never expected justice to catch up with him. He held a diplomatic post in Bulgaria before settling in the Netherlands in 1990, right before Mengistu’s regime was overthrown. He learned Dutch, obtained citizenship and interned at a university medical centre. For years he worked as a security guard – including at Schiphol Airport and the prestigious Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam. The feathers of his secluded new life were only briefly ruffled in 1998, when Dutch journalist Judith Neurink exposed him as a “torturer living next door” who had been both a “judge and executioner”. The article featured pictures of death lists with his notes on it, but sparked no judicial inquiry.

Alemu’s in absentia prosecution by Ethiopia’s Special Prosecutor’s Office (SPO) – a transitional justice mechanism set up in 1992 to record the Derg’s atrocities and put its leadership on trial – also went unnoticed in the Netherlands. During his first trial in Ethiopia in 1998, relating to 10 massacres throughout Gojam, witnesses testified about Alemu overseeing people being buried alive and kicked to death. While in 2000 he was sentenced to death for the murders, Alemu – alongside Mengistu and dozens of other Derg officials – was additionally convicted for his part in a genocidal plan to destroy opposition groups (in Ethiopia, the genocide law also protects political groups).

Only in 2009 would Alemu appear on the radar of the Dutch International Crimes Unit. Until his arrest in 2015, investigators tailed Alemu, tracking his movements, wire-tapping his phone and even communicating with him through a police informant. In Ethiopia, they obtained photographs of Alemu’s SPO files and copies of death lists. With Ethiopia barring access to the investigators (they wanted him extradited, not tried elsewhere), the Dutch followed leads into the diaspora community: first in the Netherlands, and later in the US and Canada, where 20 Ethiopian refugees were questioned. Most witnesses were victims and some put Alemu at the helm of atrocities in Gojam. Like Alemu, they too had never expected to come before a Dutch court.

No repentance

The Hague’s Palace of Justice is a busy courthouse. The atmosphere is casual. On the floor where the Appeals Court sat, a radio at an usher’s booth played Dire Straits’ Sultans of Swing. Outside the court chamber, in the communal waiting area, there was a strange rendez-vous of prosecutors, Alemu’s lawyer, victims’ counsels and a police investigator. Nestled together in a corner, sitting on uncomfortable wooden seats, gathered four of Alemu’s victims.

On 13 April they had their day in court. They had already testified in 2017 (and as “injured parties” they were awarded € 226,89 compensation for immaterial damages), and this time they had their lawyer Barbara van Straaten read their statements — in the first person. On the far right, wearing sunglasses, sat Sebene Ademe. During the first trial she had shown the judges and Alemu a picture of her brother who had been disappeared and murdered in the late 1970s. She still carries the picture with her. Listening to her lawyer, she wiped tears from her cheeks with her scarf. “I have been crying for 40 years,” the lawyer read from Ademe’s testimony. Another victim, Worku Y., testified that he was 16-years-old when he was arrested and tortured at Demmelash. He then told the court about having seen Alemu on 15 August 1978, “with a smiling face”, overseeing the massacre of 82 prisoners.

When the Court’s president asked Alemu for his response, it was a deja-vu from the first trial – during which Alemu talked a lot, and also addressed the very same victims. “These are profound, frightful events. I find it terrible what happened in Ethiopia – to me it is like a disease, like cancer,” he said. For a moment Alemu seemed to begin his repentance, saying “their grief is also my grief”. But it was a feint: “I was not there, never, when they were tortured, neither when people were put to death. What the victims say is hearsay. I am not a monster – not at all!”

Once again, Alemu sparked resentment. To Sirak Asfaw, who had attended both trials since day one, it felt like Alemu “was playing with the victims’ pains”. Himself a survivor and therefore expert by experience of the Red Terror, Asfaw found Alemu’s response incomprehensible and very painful: “It is not only an insult to the victims, to Ethiopia and to the Court, it is malicious and shows he has no remorse.”

Reading under a tree

In his public profile on a Dutch employment agency, Alemu stated that “colleagues and managers see me as loyal, reliable, stable, flexible, eager to learn, helpful, people-friendly, honest and a go-getter”. At trial Alemu equally stressed that he is “just human”. Because of his health, the chamber moved its hearings on 5, 6 and 11 April (screened in the courtroom in The Hague) to prison. In the small penitentiary room stood a dull plant. Alemu, wearing jogging trousers, sat in the middle. Despite the pain in his legs, he appeared to be energetic and sharp, still – answering, in Dutch, a barrage of questions by the three judges and prosecutor Martin Witteveen, and dodging any responsibility for each charge put to him.

On the last day of his interrogation, the presiding judge was curious to know how Alemu experienced the last 6,5 years in prison. “I know how it is to be in prison. As a student I served one month as well, guarded by military and I was tortured,” the accused replied. In the Netherlands’ jailhouse he spent all his time reading his case file – which infuriated him – and underwent chemotherapy and radiation. His entire body hurts, and at times the maximum dose of morphine patches he wore felt like psychedelics: “I almost went insane, and started hallucinating.”

“You may not survive, how do you cope with all that, mentally?” the judge asked. “I accept what has happened. That at a certain point I will die.” He said he had no mental problems, but it saddened him to miss his children, and to have never seen his grandchildren. “Suppose that you were released, what do you envisage?” continued the judge. “Freedom,” replied Alemu, “is the most important to humanity.” Often, he dreams about “going to the park, lying under a tree and reading a book until I’d fall asleep”, he said. Now, serving a life sentence, he continued, “I have no dignity”. The chamber then asked: “Do you see a psychologist, or need one?” Alemu did not hesitate: “No! Only people who have problems can deal with a psychiatrist. […] I do not see a flaw in my psychiatric state.”

The ticking clock

14 April was a busy day for The Hague’s war crime prosecutors. In a courtroom just around the corner, they won a case before the lower court, which sentenced Abdul Razaq Rafief to 12 years imprisonment for war crimes in Afghanistan between 1983 and 1987 – also committed in a prison, with similar conditions as Demmelash. For a full day, prosecutors Nicole Vogelenzang and Witteveen presented their requisitoire (closing brief). They sought a reversal of several findings and a full conviction – including for various acquittals regarding specific victims in the first instance judgement – and demanded, again, a life sentence.

The appeals case has dragged for nearly 5 years, partially because of the Covid-19 pandemic and the volatile situation in Ethiopia. But prosecutors have managed to collect additional documentary evidence (the case file holds copies of 22 letters, orders, lists and reports, each bearing Alemu’s name and/or autograph), hear three more witnesses and order three expert reports.

Because of Alemu’s condition, the prosecutors may not have expected that the appeals trial would actually take place. Now that it had come to trial, said Witteveen, they also hoped that Alemu, “knowing he will not live long” after the case ended, “would decide to recognise what he had done and ask for forgiveness”. “How naive was that thought,” Witteveen told the court. He and Vogelenzang were shocked that after his long detention Alemu would not come around. Pointing to a 54-page letter Alemu had sent the Court – explaining what he and the Derg had done for Ethiopia – Witteveen said this ideology was an “engine of the worst and cruellest that man can bring out”.

One of the largest murder trials in the Netherlands ever (only the MH-17 trial has more victims), the Alemu case is a lot to digest for the chamber. Judges are scheduled to issue their verdict on 8 June -- if Alemu is still alive.

Thijs Bouwknegt is a historian of mass violence and transitional justice at the NIOD Institute for War, Holocaust and Genocide Studies of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences (KNAW) in Amsterdam, the Netherlands.