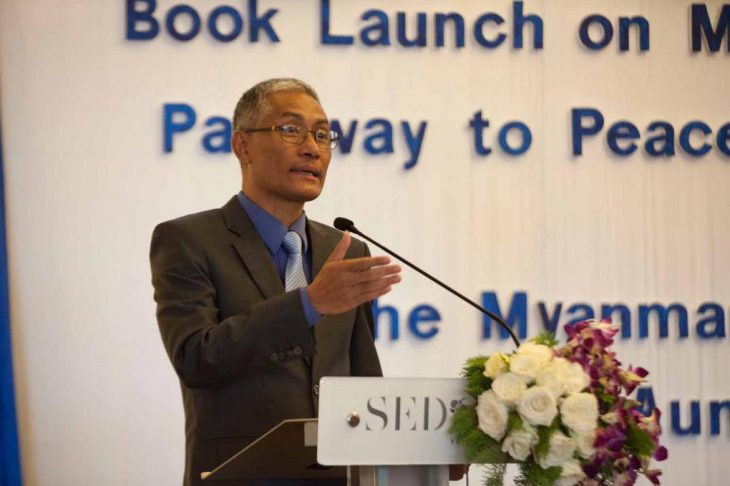

U AUNG Naing Oo spent years in the jungle fighting the government before he become a warrior for peace on the staff of the Myanmar Peace Center after it was established by President U Thein Sein in October 2012.

After the 1988 national uprising, he fled to the border with thousands of other students, joining the newly formed All Burma Students’ Democratic Front to wage armed struggle against the military regime. He spent 11 years on the Thai border and joined the MPC as a senior member of its peace dialogue program after returning to Myanmar in 2012. The 24 years he spent in exile included studying conflict resolution at the Harvard Kennedy School.

Aung Naing Oo, 51, left the Yangon-based MPC after it was abolished in May by the National League for Democracy government and replaced by the National Reconciliation and Peace Center headquartered in Nay Pyi Taw.

He is disappointed by the lack of progress in the peace process but satisfied with the contribution he made as member of the MPC. His work there is a focus of his recent book, Pathway to Peace, and he’s planning a Myanmar-language version about his role in the peace process.

It was satisfying and stimulating work, he told Frontier. “There were lots of reporters and visiting delegations and meetings full of motivation, but now it [NRPC] is boring,” he said.

The MPC had about 120 staff who worked seven days a week. This enabled the MPC to have a constant stream of dialogue with all stakeholders in the peace process, he said. The smaller team at the NRPC needs to be increased to improve its capacity to move the peace process forward, he added.

Aung Naing Oo attributed the latest fighting in northern Shan State – between four ethnic armed groups that have not signed the Nationwide Ceasefire Agreement, and the Tatmadaw (Myanmar Armed Forces) – to the “lack of talking” among the government, Tatmadaw and ethnic armed groups.

“When we [MPC] was negotiating between armed groups and government and Tatmadaw, we did a lot of talking, drinking and laughing together and it helped us to understand each other better,” he said. “The more we talk, the less we fight.”

Aung Naing Oo is not surprised by the recent fighting and says there’s likely to be more until all ethnic armed groups have signed the NCA. The obstacles to such a breakthrough include personal attachment, party attachment and differing ideologies.

A Tatmadaw (Myanmar Armed Forces) soldier stands guard as troops disembark from a helicopter at a helipad near Muse in northern Shan State on November 25, five days after an alliance of ethnic armed groups launched a surprise offensive in the area. (Teza Hlaing / Frontier)

The peace process was also complicated by issues of ethnicity, he said, referring to areas inhabited by different ethnic groups, each represented by its own armed organisation.

“It’s a demarcation problem between ethnic armed groups,” he said, and cited as an example the clashes since November 2015 in northern Shan State between the ethnic Palaung Ta’ang National Liberation Army, and the Shan State Army-South, the armed wing of the Restoration Council of Shan State.

He cited as an example the more recent fighting in northern Shan, when the Northern Alliance – comprising four groups led by the Kachin Independence Army and including the TNLA – launched attacks on multiple targets, including the highway between Lashio and Muse.

The eastern side of the highway is mainly inhabited by Palaung and Kachin and the western side by Shan. Most of the fighting occurred on the eastern side of the highway; the only clash on the western side was in Namkham Township.

Aung Naing Oo said that in the absence of an inclusive NCA he expected demarcation issues to remain a problem because ethnic armed groups had a vested interest in controlling the territory in which they operated.

“If those kind of problems still exist, the fighting will continue because natural resources are major interests [of armed groups], he said.

However, he stressed that while the NCA signed by eight armed groups in October 2015 was “not the greatest one in the world, it’s the greatest for Burma”.

In his experience of the peace process, the main reasons for civil conflict in Myanmar have not changed. Fighting in Myanmar has always been because of interests, territory, ideology, personal attachment, smuggling and control of trade routes.

Some ethnic armed groups, to his understanding, want more than what has been agreed under the NCA but their demands are impossible. “The Tatmadaw won’t accommodate them,” he said.

Aung Naing Oo was asked if he thought the Tatmadaw was being honest in its approach to the peace process.

“For me, peace is politics,” he told Frontier. “In politics, everybody works for his own objective. So it makes no difference if you ask which group is honest. I’m speaking out openly here; it only depends on how fast you can gain the result that you want. The faster, the better for peace.

“It’s true that honesty is important in politics. But in reality, everybody is working for their own objective. As for me, I don’t take honesty into account in both politics and the peace process. Because if I did, it would not work. In our peace process, it is important to gain results rather than focusing on what’s right or wrong, honest or dishonest.”

The ever-optimistic Aung Naing Oo says the latest setbacks to the peace process will be temporary.

“The current situation is one the lowest points of the peace process, but it will not last,” he said. “It will go back up.”

This article was first published by Frontier.