Currently, justice is stalled and displaced. Covid-19 has hindered the course of justice; and, as with many other pressing social issues, it has nearly banished the needed attention to combat the impunity of human rights perpetrators. Major redirection and promotion must take place for justice to not be lost. As the pandemic seems grander than life and fear takes over rationality, room for arbitrariness and injustice grows. Public and private agendas are being captivated increasingly by the spiraling logic of Covid-19.

Adaptation and response to the hardships resulting from Coronavirus crisis should not imply that we put other pressing social issues on the backburner. The current tendency to shift or pivot all or most attention to the Coronavirus crisis ignores the fact that structural social problems will not disappear but will rather (likely) worsen over time. The humanitarian and economic responses to Covid-19 are peremptory. However, those responses should not dislodge or completely supersede important social goals, such as the quest for human rights accountability.

Loss of momentum and of available resources

Promotion-of-justice initiatives and transitional justice processes have been hard hit by Covid-19. In addition to loosing momentum – caused by the consequential slowdown of judicial case loads, the halting of public hearings, and the cooling of social demands following from social distancing orders, amongst others – community-based groups and national human rights advocates, which we witnessed throughout Latin America, warn that the sustained support for these initiatives is dwindling and donors are shifting their attention to humanitarian effects of the Coronavirus. Representatives of private and public funders have, in confidence, voiced concern over drastic shifts in priorities and loss of available resources to support the promotion of justice in the near future.

Accountability for atrocities of the past was already a strongly resisted quest; the Coronavirus epidemic adds yet another obstacle. Temporary displacement of the centrality of justice initiatives can turn permanent if disregarded. Perpetrators and their backers will take any opportunity to rollback the advances of justice. The establishment of responsibilities is contentious business. Any factor favoring one of the sides can quickly alter the justice equation: in the current situation, Covid-19 weighs in favor of postponement; and postponement tends to lead to justice lost.

The Coronavirus crisis: an informational shield?

The viral epidemic is serving as an informational shield or a denial mechanism in relation to atrocity crimes committed in various parts of the world. The overload of Coronavirus-related stories has led to informative neglect of ongoing dynamics of repression and violence, for example in relation to political dissent in Nicaragua or the attacks against the Rhakine Buddhist communities in Myanmar. Likewise, armed conflicts, such as those experienced in Nigeria, Colombia, Libya and Yemen, have lost public attention; as many of the atrocities committed are not registered, denial can turn plausible.

The initial registry of a violent act by the news media is often the first bit of information that substantiates a criminal complaint in cases addressing atrocity crimes. Whether intentional or not, the current lack of exposure of ongoing torture and killings facilitates denial or obliviousness, both of which hinder the possibilities of future accountability.

This short list of situations is merely illustrative of many others that are being suppressed or smothered by the information overload of the Covid-19 crisis – another manifestation of justice displaced.

The limits of virtual hearings

After the initial shock and the passage of some time, national systems, such as in Colombia, Argentina, Singapore and the United States of America, have started to react and turn to the formulaic solution of using virtual communication to jump start judicial proceedings or transitional justice processes. However, the “virtual courtroom or hearing” solution is loaded with problems and does not provide an easy fix, even in simple cases. In relation to atrocity crimes and crimes of the powerful, the virtual solution might not be a solution at all.

Cases related to crimes of state or crimes of powerful are very contentious and litigious. These cases tend to be charged with high political and symbolic value. The virtual courtroom does little to support the magnificence and impressiveness of justice being done, or to evoke the grandeur and awe inspired by a true judicial stage. Virtual hearings suck the humanity of the justice being done, for all parties and the public.

The virtual setting is not a proper forum for complex evidentiary debates, strong procedural contention or the likely use of delay or blocking tactics that accompany this type of proceedings. Legally, at the very least, in complex cases, the virtual medium is likely to get in the way of legitimate due process concerns by all parties, and introduce prejudice. This hasty repackaging of justice runs counter to many cultural values and expectations. For example, ritualism and formality that accompany justice cannot be replicated in virtual form.

Though apparently a go-to-fix, virtual hearings are not going to cut it in cases that require that symbolism accompany the delivery of justice. In Colombia, some victims and human rights advocates have already manifested their dissatisfaction with the announcement of virtual proceedings in the framework of the Special Jurisdiction for Peace. Before the increased use of virtual means to conduct justice proceedings is embraced in places like Colombia, other alternatives should be explored, for example the physical adaptations (including spacing and transparent shields) used in the courtroom in which the German criminal case is advancing against Anwar Raslan and Eyad al-Gharib for crimes against humanity allegedly committed in Syria.

Hearings and proceedings that are not appropriate for virtual transmission need to be clearly identified and conducted in person with needed adjustments. Moreover, given that some virtual hearings seem inevitable, proper preparation, implementation and monitoring techniques need to be devised, in order to ensure that the proceedings, at the very least, do not cause harm and properly safeguard due process-related rights.

The example of the Inter-American Court of Human Rights

The tensions arising from the quick introduction of virtual tools to keep justice moving are becoming evident at the Inter-American Court of Human Rights. Pressed by a growing backlog of cases, the human rights tribunal has decided to move forward by adopting the go-to solution: the virtual courtroom. Though practical, this type of measure clashes with the conception of justice that persons who have been pursuing truth and accountability for decades are expecting. Seeing their symbolic day in court reduced to a fleeting virtual moment is not acceptable to many victims. Additionally, this measure appears to run counter to the grandiloquent rhetoric that presents that proceedings before a court of human rights as a form of reparations for victims of human rights violations.

Though convenient, the resort to virtual means can turn into an affront to the dignity of the persons that have waited decades for justice delayed.

In Chile, the attempted use of Covid-19 to get out of jail

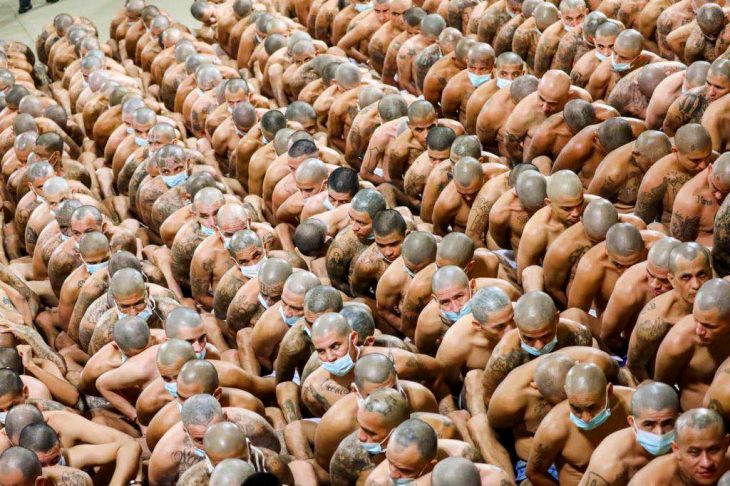

Covid-19 has also shed light on the systemic – though grossly ignored – pattern of human rights violations that take place in prisons. Sudden concern for prisoners’ rights, for example in Latin American countries, stems not from a renewed official commitment to humanity and dignity in relation to the conditions of detention, but rather from the fact that authorities want to avoid the responsibility of deaths foretold. None of the measures announced, for example in Argentina or Colombia, are tackling the structural issue: punitive expansion and absolute disregard for the conditions of deprivation of liberty.

In Chile, powerful prisoners, not exactly the ones held in crammed slammers, quickly resorted to humanitarian considerations to try to get out of jail, as all other attempts to condone their criminal convictions related to human rights violations committed during the dictatorship had failed. These convicted felons are held in a specially maintained detention facility – just for them, away from the overcrowded facilities where social distancing is simply impossible – and have access to special military hospitals.

There are no easy answers, as Covid-19 is a real threat. However, its instrumental use to grant state criminals a get-out-of-jail-free card without showing a direct link to a health- or life-threatening situation is manipulative and appeals to the irrational sense of fear that hovers close by in these Covid-filled days. In this case, some of the victims that opposed such early release attempt were accused of inhumanity – illustrating a strange twist to the bit of justice that has been procured in Chile after decades of persistent demands by victims, who also grow old and die.

This particular attempt at manipulating the Covid-crisis was averted in Chile, at least for now. However, it presents complex (ethical, political and legal) dilemmas that will arise elsewhere – for example, in the context of the Colombian transitional justice process. Consequently, the Special Jurisdiction for Peace is grappling with the early humanitarian-release for Covid-related reasons of some detainees (both, convicted and preventively held). This prospect comes at a time when detainees have not yet collaborated with the transitional justice mechanisms; thus, some victims manifest a sense of injustice. Furthermore, others have complained that early releases are not being applied evenly to members of the insurgency, generally held in degraded and inhumane conditions, and more exposed to Covid-19 risks than their military counterparts detained in special holding facilities.

Again, no easy answers!

Covid-19 responses are impacting the course of justice and the struggle against impunity. The problems and dilemmas cursorily addressed in this piece (and many more) are not going to go away. The crisis environment is fostering exceptionality and backsliding in relation to the administration of justice. Contention, adaptation and controls need to be devised to prevent the Covid-19 fevers from annulling the effects of hard-fought victories and the clearing of many obstacles found in the quest for accountability. For now, justice is stalled and displaced. We can avoid justice lost; however, we must, first, recognize and reasonably understand the occurrences and, accordingly, act strategically and determinedly to counter unwarranted changes.

MICHAEL REED-HURTADO

MICHAEL REED-HURTADO

Michael Reed-Hurtado is a Colombian/US lawyer and journalist with over 25 years of experience in the fields of human rights, criminal justice and humanitarian action, mainly in Latin America. He teaches at Georgetown University, focusing on state crime, collective violence, denial of atrocities and the sociology of lying. He is the Director of Operations of The Guernica Centre for International Justice.