"My wish is to create an archive in Saint-Denis de La Réunion so that historians can know what happened. Then I hope to be able to turn the page." Standing in front of a large cupboard full of archives, on the 8th floor of a council flat in the centre of Guéret, Simon A-Poi expresses frustration and weariness.

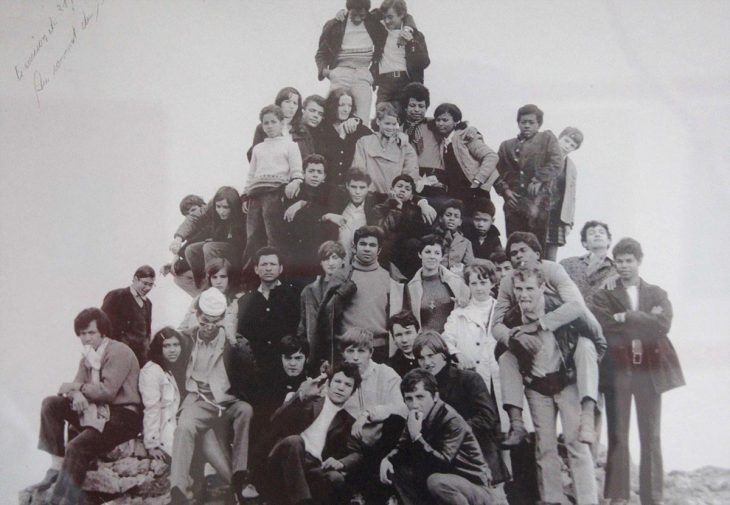

He is one of the 2,015 Reunionese minors who were "transplanted", according to the official term, to metropolitan France between 1962 and 1984. Aged between two and a half and 16 years old, these children and adolescents were orphaned, abandoned or taken from their families by court decision and had been taken into care by the very inadequate social services of this Indian Ocean island that belongs to France. They were sent 9,000 kilometres away from their homes to 83 departments of mainland France to counter the depopulation of rural areas, according to the main argument put forward at the time. Many of them landed in Guéret, prefecture of the Creuse department in the centre of France, hence they are commonly called "Réunionnais de la Creuse".

Simon A-Poi arrived there in 1966, at the age of 12. He first had a long stay in the city hostel (now converted into a hospital). Then, like many of his "transplanted" comrades, he went back and forth between host families and the hostel in Guéret. In his eyes, he was finally "lucky to find his passion", cooking, which he discovered as an apprentice and then became a cook in a medical centre near Guéret.

Judicial complaint fails

At the beginning of the 1960s, the less obvious objective of this French policy was to reduce the demographic pressure on Reunion Island, where health, social and economic conditions were difficult. The person leading the policy was Michel Debré, the island's MP and former prime minister, who approved departures to France through the Bureau for Migration in Overseas Departments (BUMIDOM). The Departmental Directorate of Health and Social Affairs (DDASS) promised struggling families a better education for their children and their return each year for a visit. In reality, many of these children went on to lose their family ties and the majority never set foot on their native island again. "We have been deprived of our family, our history and our identity," says Valérie Andanson, who was one of them.

A judicial complaint was filed against the French State by Jean-Jacques Martial, transplanted in 1966, for "kidnapping, sequestration and deportation of minors". The publication in 2003 of his autobiography, Une enfance volée, and the billion euros he demanded from the State brought attention to this forgotten page of French history. The court case also encouraged other victims to organize, seek reparation and inform the public about their history. The associations "Les Reunionnais de la Creuse" and "Rassin anlèr" (Uprooted) were created in the 2000s. About 50 plaintiffs brought complaints seeking financial reparations. However, between 2006 and 2007, these complaints were thrown out, and in 2011 the European Court of Human Rights also deemed there was no case.

Hope returns through Parliament

Then, "at some point, there was this alignment of planets," says historian Gilles Gauvin. On February 18, 2014, a resolution was adopted at the French National Assembly, "relating to Reunionese children placed in metropolitan France in the 1960s and 1970s". The resolution says that "the State failed in its moral responsibility towards these wards" of the nation, urges "that historical knowledge of this issue be deepened and disseminated" and "that everything possible be done to enable the victims to reconstruct their personal history".

The Federation of People Uprooted from Overseas Departments and Regions (FEDD), which groups various associations of victims, then put forward five demands: recognition of the "crime against children"; financial reparations (the victims hope to follow the example of Switzerland, which allocated 300 million euros to victims of abusive placements before 1981); means to be able to travel to La Réunion and be housed at State expense; access to victims’ personal files for all members of their families; and the repatriation to La Réunion of the bodies of deceased victims.

Hope returned when, on 13 February 2016 Minister for Overseas Territories George Pau-Langevin announced the creation of a Commission of Inquiry and Historical Research. Sociology lecturer Philippe Vitale, a specialist in the subject and co-author of Tristes tropiques de la Creuse, was invited to the ministry on 2 January 2016 and appointed president of this commission, which includes three other experts: Wilfrid Bertile, a geography graduate and Member of Parliament for Reunion Island; Marie-Prosper Eve, a professor of modern history; and Gilles Gauvin, a historian from Reunion Island.

For two years, the private archives of Aide Sociale à l'Enfance (ASE) on Reunion Island were consulted and interviews were conducted with former victims who spoke for the first time about their history. On 7 November 2017, Emmanuel Macron, newly elected President of the Republic, addressed a letter to the representatives of the associations, acknowledging the "fault" of the State, which had aggravated the distress of the children. Finally, on 10 April 2018, the Commission issued a 700-page report entitled "Study of the transplantation of minors from Reunion Island to France". It established the number of minors transplanted at that time as 2,015 (1,800 of whom are still alive) and recognised that their suffering and trauma had been increased by uprooting in a post-colonial context. It also reveals "the shortcomings of ASE, which from the 1960s to the early 1980s had neither the same principles, nor the same organisation, nor the same view of the child as it does today". Addressing the main stakeholders when the report was submitted, Minister for Overseas Territories Annick Girardin said that the document was "a starting point to help you heal in the present and look to the future with peace of mind".

Still waiting for reparations

Two years later, however, almost nothing has been done in the way of reparations. The report recommended 25 measures, but they have not yet been implemented. They include enhanced psychological support, access to personal documents in the archives of Reunion Island, assistance for adopted minors to recover their original identity, additional support for the repatriation of bodies to Reunion Island, and the creation of a memorial centre on Reunion Island. The victims are also calling for a day of remembrance and a resource centre in Guéret and Paris, along the lines of the Maison d'Izieu, which is a memorial to the Shoah.

The only measure taken concerns funding for an air ticket and temporary accommodation on the island. This is a mobility grant, financed by the Ministry of Overseas Territories and managed by the Union of Family Associations of Reunion, which, according to the Ministry, provides for 90% of the cost of a plane ticket to Reunion and 95% of the cost of accommodation on the island for the first three nights. This measure has been in place since 2017, before the publication of the Commission's report.

Philippe Vitale, who chaired the Commission, sees this as a partial failure. He, who has devoted twenty years of his life to this issue, feels cheated and does not understand why the State has not acted. "These recommendations [of the Commission] gave guidelines to reduce people's suffering, so that they could make peace with this painful past. But two years have passed.”

“Reunion’s elected representatives must take this up”

On November 14, 2019, victims from the FEDD gathered in Paris for a press conference, urging the government to "finally take into account their demands". According to their new lawyer, Elisabeth Rabesandratana, their pressure will be "more political than legal". "I made them understand it makes no sense to attack the State. Many have broken lives and a broken judicial past,” says the lawyer, who specializes in criminal law and has experience in international criminal tribunals.

In the face of criticism, the ministry pleads, among other things, for "the time needed for in-depth coordination work with the other public services concerned", "exchanges with other institutional players", and the signing of an agreement between the Ministry of Overseas Territories and the departmental council of Reunion Island (signed in April 2018). The rehabilitation of biological and adoptive families, the creation of a resource centre, the improvement of travel and accommodation arrangements and psychological support are, according to the Ministry, new requests made by victims at a meeting at the end of November 2019. Another meeting had been scheduled for April 2020, before the Covid-19 pandemic broke out.

For Rabesandratana, however, the time for reparations has come and one of the plaintiffs’ main weapons is public opinion. "The elected representatives of Reunion Island should take up this issue," she argues. For Valérie Andanson, spokesperson for the FEDD, "the real battle is just beginning".