The trial of former Ivorian President Laurent Gbagbo set to start on January 28 will be the first time the International Criminal Court (ICC) has tried a former head of State. Gbagbo will be tried jointly with Charles Blé Goudé, former militia leader and briefly Youth Minister, for crimes against humanity committed following November 2010 presidential elections in Côte d’Ivoire. According to the UN, the violence left 3,000 people dead. The Prosecutor alleges that the two men were part of a “common plan” to keep Gbagbo in power at all costs, even committing crimes.

Gbagbo is the third ex-president, along with Slobodan Milosevic of former Yugoslavia and Charles Taylor of Liberia, to be tried by an international court. The former head of Côte D’Ivoire was arrested in April 2011 in his presidential palace in Abidjan by security forces of his successor Alassane Ouattara, and transferred to the ICC prison seven months later. In that jail with Gbagbo in The Hague was also Liberian ex-president Taylor, who was being tried by the Special Court for Sierra Leone. Taylor was found guilty and sentenced to 50 years in prison, which he is now serving in the UK. Another prominent prisoner preceding Gbagbo was Milosevic, who was tried by the International Criminal Tribunal for former Yugoslavia for genocide and crimes against humanity committed in Bosnia-Herzegovina and Kosovo but died in March 2006 before hearing the verdict. Milosevic was sent to The Hague after losing at the polls and causing protests on the streets of Serbia in October 2000. Like Gbagbo, international justice removed him from the political scene in his country.

The Battle of History

For all three of these men the battle in The Hague is or was a battle of history. All three want(ed) to get free of the war criminal label stuck to them once they were indicted and offer future generations a different version of their past deeds. All three have claimed their judicial lot was part of an international conspiracy. Charles Taylor claimed it was Western neo-colonialism and a result of his refusal to bow to American or even Chinese demands, as his lawyer said in his last arguments, that would allow them to install their multinational oil companies for the long term. Milosevic claimed that the breakup of former Yugoslavia was fomented by Germany, the US and the Vatican. Gbagbo says it was France that supported a rebellion now in power and organized his downfall. But whatever the truth, each one was charged with crimes against civilians. The Prosecution alleges that Gbagbo used his regular troops, reinforced by militia and mercenaries to target supporters of his rival Alassane Ouattara. The Prosecutor has not shown much interest in what the rebels did, something Gbagbo’s lawyers of course mean to put in perspective.

Gbgabo’s shadow over Ivorian politics

Throughout their trials, Charles Taylor and Slobodan Milosevic promised to make stunning revelations. Taylor tried to tarnish current Liberian President Ellen Johnson-Sirleaf, with whom he started his “revolution” in the late 1980s. But his lawyer nevertheless confided that his client was not so “desperate” as to reveal all. “Can you imagine if George Bush were tried and revealed all the secrets of the CIA?” he asked. Taylor was counting on time to convince people to set him free. His lawyers constantly demanded more time from the judges. Like Gbagbo, Milosevic sometimes sought to perturb things in Serbia from his Dutch prison cell at election times. With time, however, he had to become resigned. In Belgrade, people are no longer proud of what he did. Four years after he was transferred to The Hague, Gbagbo continues to weigh on Ivorian politics. His party is divided and its candidates come to see him in prison to get his approval. As for the Ivorian government, it is following developments in The Hague closely. Its lawyers, Jean-Pierre Mignard and Jean-Paul Benoit of France, even wanted to participate in the trial.

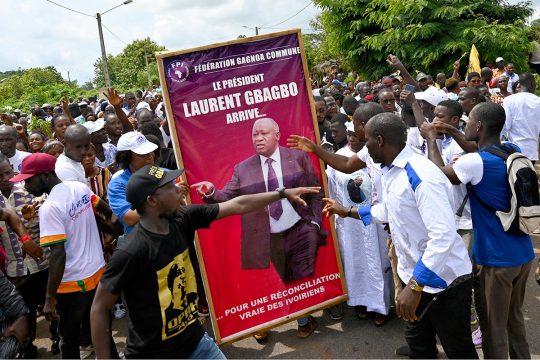

As during previous hearings, Gbagbo’s supporters plan to come in strength to demonstrate in front of the Court, whereas Taylor’s trial never mobilized the crowds. As for Milosevic, it was the victims, notably the Mothers of Srebrenica, who came by coach from Bosnia to hold him to account. Milosevic refused to be represented by others and took his own defence, giving himself a real platform which was nevertheless quickly deserted after the start of his four-year trial. Taylor, in his time, wrote questions on Post-Its to pass to his lawyers. Up to now, Gbagbo has let his defence team, led by Emmanuel Altit of France, handle the procedures. But in his first appearance before the Court in December 2011, he promised he would go “all the way”. Once they were in the hands of international justice, these ex-presidents’ peers did not defend them. On the first day of the trial, still presumed innocent, history had already convicted them in part.