Lawyer Nika Jeiranashvili has been based in The Hague for the Open Society for nearly a year monitoring progress of the Georgia case before the International Criminal Court (ICC). In January 2016, ICC judges authorized the opening of an investigation into crimes committed during the lightning Russo-Georgian war of summer 2008. But the Open Society lawyer thinks the ICC lacks a strategy and has not yet realized all the challenges it faces.

Nika Jeiranashvili

Justice Info: You have criticized the ICC Registry for lack of strategy on Georgia and the fact that the Court still does not have an office in Georgia 18 months after investigations were opened. Can you explain?

Nika Jeiranashvili: One of the biggest problems is that there is a complete lack of information. Nobody in Georgia knows what is going on, not the victims, nor the general public, nor the government. Nobody knows what the ICC is about. Nobody in Georgia has ever worked on the ICC before, which is logical because all the previous cases concerned Africa. Georgian lawyers have gone to defend victims at the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR), but the ICC is something new for everyone. Now what we are asking is that they have some kind of strategy, at least on the part of the Registry, with regard to outreach. We don’t have a field office, although last year it was promised by the Court and it was in the budget. It was argued last year that it would actually decrease costs, because the local office would be there with local staff, and they wouldn’t need to pay travel costs from The Hague, which they are doing right now. They have to pay for all this travel and they are almost every week there, from different sections, and it does not make any sense. Right now, we don’t know what’s going on. What we see so far is that there is no strategy.

How does that affect the work of civil society?

Imagine if somebody from the Georgian army is arrested. Imagine how much pressure this will put on civil society. The opposition will start blaming the government, the government will blame civil society. Then everybody will start blaming civil society, because that’s the easiest thing to do. The civil society organizations are well known, it is they who since the collapse of the Soviet Union have been trying to build a democracy. If they are blamed for everything, it will affect other things as well, because they will lose their credibility. It will not matter anymore what they think about the constitutional changes, because they will be seen as the enemy of the state, the ones who put our heroes in jail. We are asking the Court to communicate, to come and say, look, we are investigating all three parties to the conflict. But nothing is going on. Deputy Justice Minister Gocha Lordkipanidze started a campaign, meeting the public, students, and talking about the Court. The Georgian government should not have to do it! This is wrong. He might be very good lawyer, but he can’t know everything. He can’t talk on behalf of the court.

Why isn’t the ICC’s Georgia office open yet?

We don’t know. If the Court is thinking I am not going to open a field office so as not to raise expectations, I think that is wrong. Especially because it is so complex, they need a completely different approach. They need to organize meetings with international organizations, the diplomatic corps in Georgia, and try to focus their attention on the needs of victims today, nine years after the war. What are the victims’ needs, what are their living conditions? The ground must be prepared for the ICC’s Trust Fund for Victims, so that it can come and start fulfilling its assistance mandate. It is not only about Georgia, but the future -- of the country itself, the region and, in a wider sense, the future of international relations. I think if the ICC fails in Georgia, it will have a different effect from failing in other countries, not because it’s Europe and Africa does not matter, but because after so much criticism, ICC has a really good opportunity to show that it has learned from its past mistakes. But it seems it has learned nothing.

Meanwhile the Prosecutor has started her investigations…

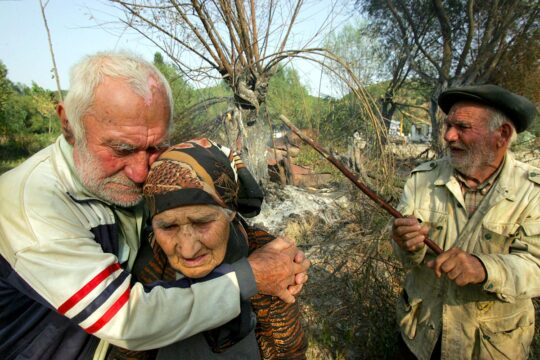

Yes, meanwhile, the Office of the Prosecutor has started its investigative activities. But now it is nine years since the war of 2008. Some of the victims have died and some of the potential witnesses are really elderly people. Investigators can’t just go to victims and say, hey, I come from The Hague to investigate crimes committed nine years ago. There is certain issue of trust. They need to build a special relationship, and the only link is through civil society, because civil society has been involved since 2008. They have documented crimes, represented victims in Strasbourg, provided legal aid on various issues. But there is already some discouragement. First of all, there are very few organizations that work on related issues. They are not funded to do it, it’s all on voluntary basis, and if they see things continuing like this, they will simply not help the Court any more. They work on various current issues in Georgia such as justice reform, constitutional reform, illegal surveillance, witness interrogation technics, police reform. And if the court is thinking to continue this way, then next year there will be nobody left from civil society to help the Court. I have already heard from colleagues that if they had known years ago how the Court operates, they would never have asked the Court to open an investigation. These are people who documented the crimes years ago, who met the victims, the families, but now they see what’s going on and they are losing hope. The problem with the OTP is that it can’t go much further unless there is communication with victims and potential witnesses. If they don’t know what the process is about, they will simply not participate. They don’t want some people coming asking questions about what happened nine years ago, especially if they don’t know what the process is. There are security risks for them, especially those who are living close to the administrative line [between South Ossetia and the rest of Georgia]. If the Court sends people who are not experienced with the region and don’t know the cultural aspects, they won’t be able to establish any contact.

What impact do you think the ICC can have on Georgia?

This process will have a really huge effect on the future of our country, especially when it comes to foreign policy. In Georgia, if you look at our history, we have always looked to the West or Russia. If the Court fails, it will be not only the failure of the ICC but of the West as such. That’s how the public will perceive it. I do not think that people at the Court thought about all that when they set foot in Georgia. They were stepping outside Africa. But they are slowly starting to understand there are many challenges linked to this crisis.

What are the challenges?

This is the first time that the ICC will be dealing with international crimes, because before it was always an internal conflict [the Court has not dealt with the international aspects of internal conflicts it has investigated, such as in the DRC, Libya and Côte d’Ivoire]. This is not only the first international conflict, but it also involves a really powerful UN Security Council member State which has already said it is not going to cooperate with the Court. It was really symbolic that Putin told the ICC Assembly of States Parties that Russia basically does not care about the Court [in November 2016, the Russian President announced he was withdrawing his signature from the ICC Treaty, which Moscow has never ratified]. I think it will create a lot of challenges with the execution of arrest warrants. Imagine a situation where the Court asks certain member or non-member States to execute arrest warrants against some Russian Generals. It would be almost a declaration of war for a State to do that. And if nobody is brought to The Hague, there is nothing, no trial, no reparations. This is something that the Court should already be thinking about. The problem is that if they are not on the ground, there is nobody there to manage expectations. What happens if they are not there? Everything is politicized in Georgia. Politicians will blame this politician, that party, the country. If there is nobody from the Court to balance all this, then it will be a complete disaster.

During the Prosecutor’s preliminary examination (2008 to 2016), Russia seemed to cooperate with the Court. What do you think about that?

Yes, Russia said it had submitted to the Court 30 chapters of criminal investigations. Initially they were really angry with the wording of the decision to open an investigation and said the ICC is biased. They said they sent documents against former president Saakashvili and his regime but he is not mentioned anywhere. Putin’s statement in 2016 was a clear message to the Court: “don’t even try, we are not going to cooperate”. It is not only that they are not going to cooperate, they will do anything for this process to fail. The Court has no idea what they are dealing with, because they don’t have experience of dealing with Russia. I know that they have experience with Kenya, when the State was not cooperating, but that is nothing, with due respect, not because Kenya is in Africa but because the Court is now dealing with Russia.

Do you have the impression Russia is trying to interfere in the ongoing investigations?

We have not seen any activities that we could attribute to Russia. It will take some time, as the process develops. Right now there is nothing, no accused, no witnesses. But if at some point there is an arrest warrant issued, for sure they will interfere and their interference will be something that the Court has never experienced before. Russia does not really care about the Court at all, at least for now. This is a country involved in two conflicts being examined and investigated by the Court [Georgia and Ukraine, which is the subject of a preliminary examination], and which is a member of the United Nations Security Council. You don’t need deep analysis to know that there will probably be no cooperation. What we would like to see is for the Court to actually know this, to anticipate. It all looks nice in The Hague, with a huge, modern building, 800 staff, everyone dressed nicely with their suits and ties, and they seem intelligent. But when we talk with them, we don’t know if they have the whole picture.

What about Georgia?

The government, Prime Minister and Minister of Justice are cooperating with the Court, but it’s just the beginning. And they don’t really have time to think about the ICC. If there is an arrest warrant against a Georgian, then things might change in terms of cooperation, depending on whether it is against a member of the military, the previous government or the current government. If it is former president Saakashvili [Mikheil Saakashvili, who was naturalised Ukrainian in 2015, was governor of Odessa before forming his own political party in 2016], I think the current government will be very happy about it, Ukraine’s current government too, and I am sure that Russia will be happy about it. For us, it doesn’t matter. If you commit crimes, torture people, it doesn’t matter from which ethnicity you are or who you are. Stalin was Georgian, and I don’t think he was a good person.

Are you saying that the ICC’s intervention in Georgia is Mission Impossible?

I don’t think it is mission impossible, but what we are trying to do is to have two dimensional approaches to this whole process. We don’t look at it as a strictly ICC process, but we look at the wider picture. What we want is to bring international attention to support victims on the ground and to do it now. This is probably the most important thing to do. We know it is a very complicated process and very slow. But in seven or ten years it will mean nothing to the victims, who will probably be dead.

Is drawing international attention really part of the Court’s mandate?

Have they done justice in any situation? Is it not their job to start the assistance mandate? Or are they going to start after nine or ten years? The whole reason we have the Court is to investigate such crimes and basically to stop a small country being bullied by a bigger country. That is putting it bluntly, but in a way that’s the whole idea behind the Court. If it fails in Georgia, it will be the same in Ukraine and in situations where powerful States are involved like Afghanistan or Palestine. That is why the Court needs to be extremely active, really fast. What happened in Kenya or the Central African Republic should not be an excuse. Now the whole attention of the Court is on the election of new judges and the Registrar. The Registrar wants to run again, which is interesting, but what is his position on Georgia? We have not heard anything from him. If he wants to run again, then he should be a role model. And maybe we have to think if he is the right guy for this position. If the Court fails to bring assistance to the victims and prosecute those responsible for crimes, then it will affect our whole foreign policy, and people will start to wonder why we need this Court. In a way, that is an existential question for the ICC.