On 28 February 2013, at the end of the International Criminal Court’s confirmation of charges hearings, former Ivorian president Laurent Gbagbo told the trial chamber that once the case against him was finished, “whatever the result may be”, he would share a batch of his history books with the ICC Prosecutor’s office. Nearly six years later, after finishing writing two additional books in The Hague’s Scheveningen prison, he may want to keep his promise.

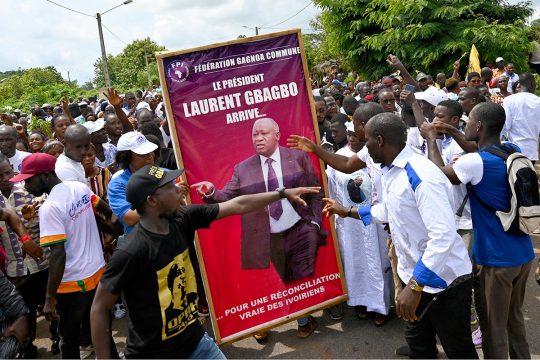

On 15 January 2019, Gbagbo and his former Youth Minister Blé Goudé were acquitted by the trial chamber. They did not even have to present their case. It was a bitter start of the year for the ICC. It was its first hearing in 2019 and the only people reveling in The Hague were Ivorians. On the Court’s crisp doorsteps, they were drinking champagne and singing in rejoice of the acquittal decision. For the international justice community, and for victims back in Côte d’Ivoire too, it was a moment of tremor, defeat, disillusion, and despair. Once again, the world’s court of last resort that is to speak justice to power had ordered the release of government officials suspected of mass atrocity crimes. Since its beginning, the trial was politicised, theatrical, emotional, controversial and uneasy. However, its abrupt ending midway – after two years of prosecution evidence and one year for the judges to make an evaluation of it – was barely surprising. Overall, the trial suffered from an implausible case theory, lack of evidence and paradoxical testimonies.

Should it have gone to trial at all?

If it was for Christine van de Wyngaert to answer, it would have been a decisive no. Last weekend in an interview to a Belgian newspaper, the former ICC judge echoed how profoundly feeble she found the evidence in the case, which she called “a fiasco.” She said she had seen the acquittal looming in the air, like a dark cloud, for more than five years.

No proper investigation

From the beginning, the Prosecution had built its crimes against humanity case on anonymous hearsay evidence from NGO reports and press articles. Such pieces of evidence may serve as first drafts of history, sketch context and provide leads, but they cannot, wrote the pre-trial chamber in June 2013, “in any way be presented as the fruits of a full and proper investigation.” In a somewhat unexpected move of judicial lenience, the same pre-trial chamber – of which van den Wyngaert was a member – gave the ICC’s Prosecutor’s Office (OTP) five extra months to collect evidence that would withstand the lowest threshold of legal scrutiny required to confirm the charges. But the writing on the wall was clear of what was going to happen if the Prosecutor could not deliver.

The rest is history.

Getting presidents and ministers convicted of mass atrocities might have felt easy to the OTP. But practice, so far, has demonstrated the opposite. Proving that political responsibility also amounts to criminal responsibility ideally may demand deep expertise on the political history of a “situation”, systematic inquisitorial investigations and bringing realistic charges. This is not what we saw in the Gbagbo-Blé Goudé case – as well as in previous ICC cases from Africa.

Ignoring warnings from experts

The ICC had its eyes on Côte d’Ivoire as early as October 2003, when Gbagbo himself, then president of the country, sent a letter to The Hague accepting the Court’s jurisdiction over crimes allegedly committed by rebels in the Northern part of the country. But the OTP only responded to Gbagbo’s opponent Alassane Ouattara’s 2010 invitation to initiate a proprio motu investigation. The move was supported by human rights lobbyists and international political figureheads. After Gbgabo triggered a bloody crisis in December 2010 by refusing to relinquish power after an election defeat, he was defeated by forces supporting Ouattara and was arrested in April 2011. Back then, the late historian and West-Africa expert Stephen Ellis was already concerned about the way the ICC operated. They “sometimes run ahead of their ambitions,” he said. He and other experts on mass violence in Côte d’Ivoire warned that a criminal case against Gbagbo for the political violence between December 2010 and April 2011 would not fly. But the OTP followed suit nonetheless.

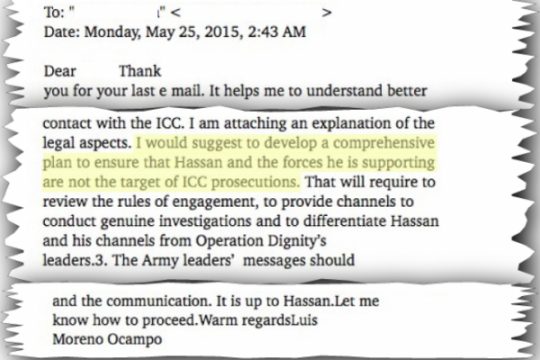

In May 2011, Fatou Bensouda, then deputy prosecutor in charge of preliminary examinations in West Africa, said the ICC was “poised to receive the file” from Abidjan. For the then prosecutor Luis Moreno-Ocampo, Gbagbo was the obvious target: he was in prison, he featured as a bad guy in the press and the new regime provided access to presidential records and insider witnesses.

Political manipulation and simplistic narrative

On 24 November 2011, in Paris, President Ouattara and Prosecutor Moreno-Ocampo orchestrated Gbagbo’s prompt transfer to The Hague, based on a sealed indictment, according to evidence revealed by a consortium of newspapers in 2017. Investigations would follow. But for a presidential case, the inquiry was marginal. By February 2012, the OTP had only eight investigators on the ground. Working with Côte d’Ivoire’s main human rights groups to record witness testimonies, they were focusing on preparing for Gbagbo’s confirmation of charges hearing.

Fatou Bensouda wanted to “send out a strong message to those who intend to attempt to get to power, or to remain in power, by use of force and brutality, to tell them that they shall henceforth be answerable for their actions.” Like in Kenya, the OTP sought to only deal with contemporary messy political violence in the chaotic, blurry wake of contested elections. And indeed, at first sight, the charges against Gbagbo seemed clear-cut: four violent attacks against unarmed civilians in Abidjan. It could have worked if the underlying case theory was not the Prosecution’s Manichean narrative on Gbagbo’s decade-long presidency and his virtually despotic determination to cling on to power by criminal means.

In reality, the prosecution’s case theory relied on such a simplistic understanding of Côte d’Ivoire’s political history that it was bound to fail. No reasonable judge, or first year history student, could be convinced that Gbagbo, his wife Simone and his protégé Blé Goudé had hatched a criminal plan in 2000 to “keep him in power by all means”, only to implement “a state or organisational policy aimed at a widespread and systematic attack against perceived Ouattara supporters” in 2010.

During trial, the judges already signaled they found the Prosecution narrative, which was broadly outside the scope of the charges, implausible. The OTP presented 2679 documents, including the presidential palace logbooks, police records, UN reports, medical reports and Simone Gbagbo’s diary. None of these documents contained a single Nazi-style record of crimes against humanity, let alone presidential orders to commit such acts. In absence of a documentary trail, the OTP resorted to human rights reports, a documentary, press footage and testimonies.

82 witnesses and no corroboration

At trial, hardly anyone corroborated the case theory or linked the charges to Gbagbo. From day one, in January 2016, witness testimonies were laborious, nonsensical and at times absurd. Presiding judge Cuno Tarfuser jokingly observed that “at this pace we [will] finish this trial in 2050.” Then he became increasingly impatient. Besides a former Human Rights Watch researcher, a British documentary maker and a UN investigator, no real independent expert was called to outline what exactly happened in Côte d’Ivoire, who had actually been involved in violence and how. After hearing 82 witnesses, it remained forensically unclear who did what to whom.

Who killed 150 people, raped 17 women and injured 111 others, as listed in the indictment, during the attacks on the national Radio and Television headquarters, Abobo’s women march and the shelling of Abobo’s market?

Nobody questioned that this violence took place, including the trial judges. But insider witnesses, including a score of police officials, generals and politicians, could not provide a beyond-reasonable doubt picture about who was responsible. Their testimony was generally unspecific, ambiguous, evasive or even exonerative, particularly when it concerned Gbagbo’s role – and of course their own – in the events. Other witnesses, including opposition politician Jichi Sam Mohamed (a.k.a. “Sam the African”), took the stand for opportunistic reasons and turned hostile to the Prosecution who had called them.

Lessons from an underdog

It was after 220 sessions, many of which behind closed doors, that the prosecution closed its case in January 2018. It must have felt confident as it cancelled 44 witnesses initially announced to testify in The Hague. The trial chamber, however, was not. It soon requested the OTP to file a trial brief in which it was to summarise, organise and clarify how the evidence presented related to the charges and the case’s scenario. This was an uncommon request. And it was obviously telling about the trial chamber’s confusion over the relevance of what they had heard over the course of two years.

During combative proceedings, virulent cross-examinations and in front of a public gallery filled with Gbagbo supporters, the prosecution fought the case as if it were the underdog. In so doing it kept holding on to its bone for too long, blindly believing in its tunnel-visioned version of history. The case is eventually emblematic of the OTP’s incapability to effectively investigate atrocity crimes in Africa. The problem is widespread and systematic as evidenced by the ICC’s feeble conviction record. Should we fault the Office of the Prosecutor for it? Yes, to some extent. It should reconsider if it should continue to act as the executive, judicial, arm of major international human rights NGOs, and work in a more inquisitorial, independent manner. That includes deciding not to push cases if there is insufficient evidence.

No worries for the states

But we must also be aware of financial constraints. States supporting the Court have maintained it on a shoestring budget. By 2018, the ICC only had 61 investigators, 23 analysts and 9 staff in its forensic science section. That is extremely modest for a court that deals with no less than 21 situations across the globe. By comparison, the ICC says that the UN Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia deployed between 20 and 30 investigators per case – excluding lawyers and other supporting functions. Financial and political backers of the Court have been perfectly successful at maintaining a court that is imperfect when it comes to holding to account government officials. The Gbagbo trial reassured them that they have little to worry from this court.

As to Laurent “Koudou” Gbagbo, while he may have to wait for the appeal’s procedure, he now stands among an illustrious group of powerful figures who have contributed to the unnecessary humiliation of his accusers at the ICC.

THIJS BOUWKNEGT

THIJS BOUWKNEGT

Thijs Bouwknegt is a historian and former journalist. He is a Researcher at the NIOD Institute for War, Holocaust and Genocide Studies in Amsterdam, The Netherlands, and Assistant Professor at the universities of Amsterdam and Leiden. His research focuses on the history of transitional justice, particularly in Africa. Since 2006, he attended and covered all ICC (pre-) trials in The Hague, including the Gbagbo and Blé Goudé case.