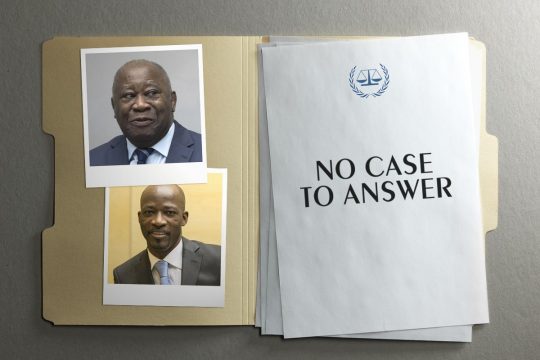

In the three hundred pages of her dissenting opinion, Dominican judge Olga Herrera-Carbuccia took the opposite view of the majority's decision. For her, it was clear that in the case of the prosecutor Fatou Bensouda, there was "sufficient evidence, if accepted, on which a reasonable Trial Chamber could convict the accused. »

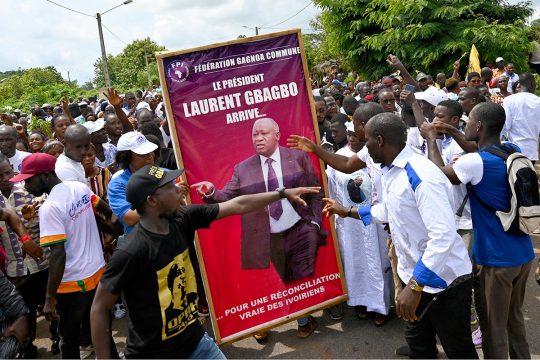

To reach this conclusion, she adopts an approach different from that of the majority; rather than verifying (and invalidating) step by step the case of the prosecutor like the two other judges, she pays particular attention to the documents and testimonies presented before the Court in order to make up her own mind. Unlike the majority and although in a brief manner, she recalls the presence of victims (through their counsel) at the trial. And in one of the first paragraphs, she decides, before addressing the merits of the case, to describe the objectives, in her view, of international justice: "Establishing the truth behind events and preventing all forms of revisionism have always been the underlying objectives of all international criminal justice systems. If we allow a president in a democratic society who refuses to step down in the aftermath of a contested election to target citizens of that society and commit crimes against humanity with impunity, we fail to comply with the values and purposes enshrined in the Rome Statute ("Statute")... and espoused by the international community. »

A common plan

In her analysis, Judge Herrera-Carbuccia draws on the case law of the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY). Through the Limaj judgment, she seeks to show that attacks against the civilian population are often carried out by a State. "It is States which can most easily and efficiently marshal the resources to launch an attack against a civilian population on a ‘widespread’ scale, or upon a ‘systematic" basis’”, she quotes, citing the ICTY decision. She concludes that it is not then necessary to prove that there was an "inner circle" (as in the Prosecutor's theory) operating around former Ivorian President Laurent Gbagbo and sharing the desire to keep him in power at all costs.

"In the case at hand," writes Herrera-Carbuccia, "the analysis must be centred on whether Mr Gbagbo and the State apparatus he led, which included among others his cabinet and senior FDS [Defense and Security Forces] officials, implemented a policy to attack the civilian population.” Targeting the use of mercenaries and pro-Gbagbo youth, the former university dean says that "it is important to determine whether these private elements, although not legally within the State structure, interacted with the State in the implementation of the State policy". The analysis of the evidence presented in connection with the attacks allows her to meet the above criteria in the affirmative.

Crimes against humanity

The judge goes back to the march on Ivorian Radio and Television in December 2010. "Contrary to the submissions of the Defence, there is ample evidence that the FDS hierarchy and Mr Gbagbo were aware that the march was going to take place and that meetings had been held to organise the repression of the march, which was to be prohibited upon Mr Gbagbo's order." She continues: "The evidence also supports the allegation that Mr. Blé Goudé reportedly summoned youth leaders to march on RTI.”

Herrera-Carbuccia mentions a video excerpt from December 12, 2011 in which Interior Minister Emile Guiriéoulou talks to the police about the measures to be taken during the march. The judge quotes the Minister as follows: "We are in a situation that is not a normal situation. So I reminded the prefects that we are in a situation of war and that in a situation of war, special measures must be taken, and that we must not be satisfied with the usual administrative measures, that we must integrate into our behaviour, our actions, our reactions, that we are in a situation of war.”

Testimonies would confirm allegations that unarmed civilians were beaten, detained and killed on 16 December 2010. For the judge, a reasonable trial chamber could therefore conclude that the Defence and Security Forces with other non-State actors have failed to "to perform [their] duty to protect civilians". The judge considered that "the State apparatus attacked unarmed civilians and refused to take measures to protect the people". Even if civilians took part in an unauthorized demonstration, the use of lethal force and "manifestly criminal acts such as rape... is unjustifiable". The judge made a similar observation for the march of Abobo women in March 2011. "The evidence attests to the allegation that the SDF" showed "excessive use of force by firing indiscriminately at a crowd of unarmed women," writes Herrera-Carbuccia.

Command responsibility

The majority analysed in detail all the articles of the Rome Statute under which suspects were charged. Herrera-Carbuccia takes a different approach. " Judges are limited, in their analysis, to the facts and circumstances of the charges confirmed against the accused," she explains. "However, [...] judges have a discretion to examine only the mode of liability that most accurately describes the conduct of the accused." It is on this basis, and "in the light of Mr Gbagbo's position as President of Côte d'Ivoire and Supreme Commander of the FDS, and the fact that he had the capacity to issue instructions during the post-election violence" that the judge decided to analyse the former president's responsibility under article 28, which defines the "responsibility of military leaders and other superiors".

Article 28, for Herrera-Carbuccia, "was included in the Statute to prevent impunity for those in power - those who, by traditional criminal law standards, would have escaped justice. The essence of article 28 is that it holds responsible those who, under the veil of the rule of law, in fact abuse the rule of law against the population they are supposed to protect." Returning to Gbagbo and to the march on the RTI, Carbuccia-Herrera argues that "although there is no evidence that Mr Gbagbo explicitly ordered the commission of these crimes against civilians, evidence shows that his order to repress the march was implemented in a brutal manner. Evidence also suggests that this violence was planned.” She mentions a televised speech in which "Mr. Gbagbo confirmed that he had knowledge of the civilian casualties. However..., no action was taken to punish those responsible for perpetrating the crimes. »

Blé Goudé could also be convicted

The situation concerning Blé Goudé is different. Article 25(3)(b) would apply, i.e. ordering, soliciting or inducing the commission of crimes. For Herrera-Carbuccia, the evidence confirms that Blé Goudé "was a close and trusted associate of Mr Gbagbo [...], was a Minister in Mr Gbagbo's government while remaining ‘The Street General’" and "had de facto control over FDS officers of the so-called ‘Génération Blé Goudé’".

The "street general" could therefore be convicted for crimes against humanity following his many speeches and "watchwords" asking Young Patriots to act for Gbagbo, even with "bare hands". She justifies this by the fact that Blé Goudé never asked the young people to put an end to the killings, as with the use of "article 125" when he was aware of the commission of these crimes by the young people under his leadership (100 francs of gasoline and 25 matches to burn suspects alive).

Judge Herrera-Carbuccia does not say that Gbagbo and Blé Goudé are, in her view, guilty of crimes against humanity. She only answers in the affirmative to the question put to the Chamber: on the basis of the evidence and arguments presented during the prosecution case, could a reasonable Chamber convict the accused? And she would have liked the defence to be able to present their arguments before the Trial Chamber.