“I am completely recused,” said earlier this month the International Criminal Court (ICC) prosecutor Karim Khan when pressed by journalists about his role in the case that was concluded yesterday against a Kenyan lawyer, Paul Gicheru, accused of interfering with witnesses while Khan represented Kenya’s deputy president William Ruto. “I am not involved. I don't receive the evidence or the emails. This is dealt with by a deputy prosecutor. I won't comment further,” said the incumbent ICC chief of prosecution.

If Khan were open to questions, they would centre on what role he played as defence counsel in one of the ICC’s most notorious defeat. The case on charges of crimes against humanity against Ruto and fellow defendant Joshua Arap Sang, a radio broadcaster, collapsed in 2016. The main case against Ruto, and the other one against his opponent who then became his election partner Uhuru Kenyatta, concerned the ethnic violence which ripped through serval communities in the country following the election at the end of 2007.

Some 1.100 people died and around 600.000 others were left homeless.

Witness interference

The then presiding judge described a "troubling" pattern of "witness interference". 16 out of the 42 witnesses had changed their stories or refused to testify. The prosecution alleged the changes were due to intimidation, bribery or fear of reprisals. Ruto and Sang’s lawyers successfully argued that the court should not allow previous recanted testimonies. That left a bitter taste in the prosecution’s mouth, who couldn’t use the testimonies key to his case.

During Khan’s candidature to the post of ICC prosecutor, Kenyan civil society critics noted that he had been intimately involved. His “closeness with his client” led him to adopt Ruto’s political posture and language, one prominent human rights lawyer told Justice Info, “bullying” and “silencing” civil society. It was a “very slippery space for a defence counsel”.

Truth out of contradictions

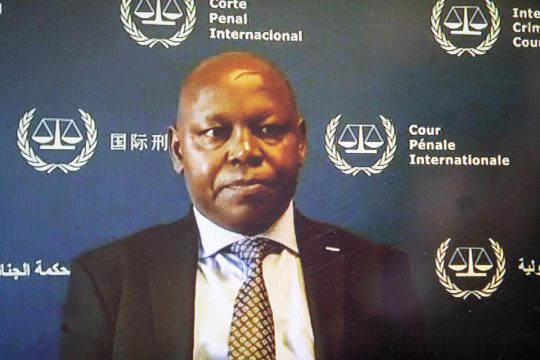

On Monday 27 June, the judges heard the closing arguments in the case against Gicheru. The Kenyan lawyer played an “essential role” states the ICC prosecutor Anton Steynberg in what he describes as a ‘common plan’ “to locate, contact and corruptly influence witnesses and potential witnesses in the Ruto and Sang case to withdraw and/or recant their evidence and cease all cooperation with the Court.”

The prosecution had called eight witnesses to testify. They were either alleged recipients of bribes or had been involved in the alleged scheme, and had previously made statements to the court that their latest evidence contradicted. Nevertheless, Steynberg told the court it should be “no surprise” that some had lied previously; their evidence should now be assessed individually to see the picture built up. “Inconsistencies, contradictions and inaccuracies may in fact speak in favour of the truthfulness of the witnesses account”, states the prosecution closing brief.

The case was precipitated by Gicheru himself, who contacted the Office of the Prosecutor in 2018, recalls his lawyer Michael G. Karnavas. “My client reached out to the ICC. He just wanted to clear his name and get this thing over with. He just showed up at The Hague. He would like to be able to travel outside Kenya.” Then Gicheru travelled to The Hague in 2020.

Gicheru’s move set Kenyan political commentators alight with speculation that he might be prepared to spill the beans on the machinations behind the collapse of the trial, and thereby weaken Ruto’s chances of becoming president after having been Kenyatta’s vice president during more than nine years. But as Kenya is in the middle of another presidential race, Gicheru has remained tight-lipped, and Ruto remains the leading candidate.

The prosecution was unsure how to look at this ‘gift horse’. In its closing brief it described Gicheru’s “demeanour” during interviews as “evasive, failing to maintain eye contact, looking around while speaking or taking long pauses before responding to questions.” To substantiate their allegations about his central role, it brought evidence such as bank records, mobile phone recordings.

The defence also poked holes in these forms of evidence, pointing out where they failed to directly connect to Gicheru. Karnavas suggested in its own closing brief that phone recordings were staged to provide evidence for the prosecution. That’s “fanciful in the extreme”, replies the prosecution. “It would require consistent coordination between the persons alleged to be responsible from diverse locations across the world and over a period of seven years, even persisting well after the supposed rewards had been received”, it said.

“Confabulators of Olympic proportion”

“Corrupted by tunnel-vision due to a combination of ineptitude, indifference, lack of due diligence, self-imposed restrictions on investigating in the Rift Valley and elsewhere, and with no small measure of pre-conceived result-determinateness, the Office of the Prosecutor (“OTP”) investigators conducted an irreparably flawed investigation, based on the lies, hearsay, and unsubstantiated claims by grifters, opportunists, con-artists, and confabulators of Olympic proportion”, the defence didn’t hesitate to write in its brief.

The defence presented no case and no witnesses. That is because they assessed “there was insufficient evidence” that they had to counter, Karnavas explained to Justice Info. Instead, he concentrated his fire on the prosecution methodology in Gicheru’s case: “The OTP’s investigation is a textbook lesson on how not to conduct an unbiased, methodical, and diligent investigation where the sole objective is to let the evidence lead where it may, as opposed to having a predestined outcome lead the evidence”, reads its written brief.

“Myopic approach by the defence”

Prosecution “expects the Trial Chamber to find the needles of truth – if any exist – hidden in the massive haystacks of lies by each witness, inaptly cherry-pick through the witnesses’ accounts with preference accorded to the most recent versions produced through countless and ever-evolving ‘clarifications,’ and to step into the breach and fill in the gaps. The evidence – if viewed holistically and objectively – does not rise to the level of proof beyond a reasonable doubt,” reads the defence brief.

Interviewed by Justice Info, Karnavas does not mince his words either: “It is up to them to prove their case. If they are going to parade a bunch of liars and grifters. If the evidence is full of holes. If the witnesses are contradicting themselves. If they are relaying on hearsay evidence, why should I as defence counsel try to find evidence to the contrary.”

Steynberg described this as a “myopic approach by the defence” to the court, “assessing each witness in isolation and refusing to acknowledge the bigger picture the prosecutor case painted”.

The short trial began in February 2022 before single judge Miatta Maria Samba who will now assess the credibility of the witnesses and whether the evidence proves that Gicheru was responsible for a scheme to interfere with a case at the ICC.