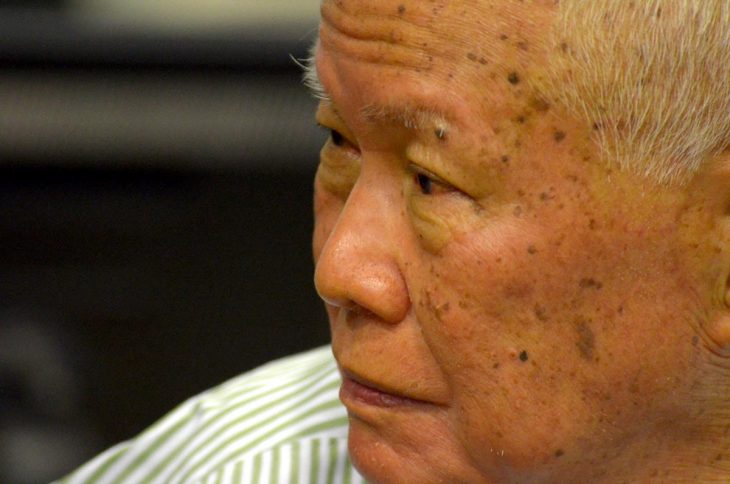

More than 43 years after the fall of the Pol Pot regime, which claimed the lives of about a quarter of the Cambodian population between April 1975 and January 1979, the last survivor of the five Khmer Rouge leaders prosecuted under the international justice system has been definitively sentenced to life imprisonment for genocide, crimes against humanity and war crimes. The Appeals Chamber of the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC) - more commonly known as the Khmer Rouge Tribunal - handed down its ruling against Khieu Samphan on September 22 in Phnom Penh, the Cambodian capital.

This judgment marks the end of the laborious judicial work carried out by this court composed of both Cambodian and international judges. It does not bring any surprises or new facts. The conviction of Khieu Samphan on appeal confirms, four years later, the judgment of the trial court and seals for history this court’s legacy.

Evaluating the ECCC remains a dilemma. On the one hand, there is the frustration caused by the meagre number of trials conducted, political interference, the mediocre career interests of its staff who sought to perpetuate the court forever, and the accusations of corruption. On the other hand, there is the historic judicial recognition of the crime committed, the public exposure of the facts and the unprecedented meeting after 30 years that Cambodian society was able to have with this unprecedentedly brutal part of its history, which spared no family in this small south-east Asian kingdom.

Three convicts in 16 years

It took 16 years for the court to convict three people.

Kang Kek Leu (pronounced Kang Guek You), better known as Duch, was convicted of crimes against humanity in 2012 and sentenced to life in prison. The former director of S-21 prison, where at least 12,700 people perished (the majority of them former Khmer Rouge purged by the regime), died in 2020. He was the only one of the dignitaries on trial to acknowledge the essence of his crimes and the criminal nature of the regime.

Ieng Sary, former foreign minister and brother-in-law of the all-powerful Khmer Rouge leader Pol Pot, died in prison while on trial in 2013. His wife Ieng Thirith, former social affairs minister, was declared unfit to stand trial due to senile dementia. She died in 2015. Nuon Chea, the regime's former Number 2, was sentenced to life imprisonment for genocide, crimes against humanity and war crimes, along with Khieu Samphan, but he died before the end of the appeal process in 2019.

Before them, the feared military leader Ta Mok also died in July 2006, as the ECCC judges were sworn in.

Apart from these individuals, the Cambodian government, led for 37 years by former Khmer Rouge Hun Sen, blocked any move to prosecute four other officials. This was thanks to the obedience of Cambodian prosecutors and judges and, as written by Heather Ryan who observed the ECCC from start to finish for the NGO Open Society Initiative, the cowardice of the "United Nations, international officials and donors to the Court [who] are also to blame for not honestly and publicly acknowledging the political impediment to independent judicial review of these cases”.

"No sense of real justice"

After the spectacular and rather quickly concluded Duch trial in 2009, the ECCC forgot about the urgency of trials. It took 11 years from the arrest of Nuon Chea and Khieu Samphan to their trial on the most serious charges. So much time passed that even the official ECCC website stopped updating Khieu Samphan's file in 2017.

In 2018, on the eve of the conviction of Nuon Chea and Khieu Samphan, historian David Chandler said of this tribunal - which will have cost at least 400 million dollars - that it was "now on its last legs and many will welcome its disappearance from the scene (...). As the ECCC edges toward that spongy concept, closure, many people in Cambodia and elsewhere believe that it has run its course and feel that it has passed its use-by date and ran out of relevance long ago." Ou Virak, a Khmer Rouge survivor and courageous activist for the rule of law since the 2000s, agreed. "I believe that the verdict does not bring any sense of real justice and that most Cambodians have given up any hope of justice or even appeasement," he said that same year.

This feeling will be compounded by the fact that, despite much rhetoric from international justice experts and activists, the hoped-for impact of the ECCC on the functioning and independence of the national judiciary and strengthening of rule of law has not materialised. Today's Cambodia is marked by a judicial system riddled with corruption and totally at the orders of Hun Sen's authoritarian regime, which has long used it as a tool for repression of its opponents. Democratic freedoms, both in terms of political participation and freedom of information, have been lost during the ECCC's existence.

"Considerable interest"

Yet despite some of the worst judicial inefficiency in recent international criminal justice history and a deeply compromised moral standing, the ECCC leaves a number of accomplishments behind.

Chandler believes that the Khieu Samphan and Nuon Chea trial remains of "considerable interest" because of the mass of archival material collected, the fact that 100,000 Cambodians had the opportunity to attend these historic hearings, and the fact that the ECCC allowed for a national public debate about crimes that were not taught in schools until 2009. "For years, the teaching of Khmer Rouge history was propaganda. Now it is more balanced, more fair," said filmmaker Rithy Panh, a tireless worker for remembrance of the Khmer Rouge cataclysm.

The Khmer Rouge Tribunal was the only international tribunal dealing with the crimes of communism. It was also an important experiment in terms of the participation of victims, who enjoyed full status as parties to the trial. This participation is considered the most effective and massive that UN criminal tribunals have organized. More than 3,800 victims participated in the trial of the two senior leaders, even if most often from a distance and in a small way, as the former co-lead counsel for the victims Marie Guiraud recounted. The end of the ECCC remains marked by frustration on the issue of reparations, a reality underlined by the resignation last June of the last international lawyer for the victims, Megan Hirst.

This judicial undertaking, begun 30 years after the events, will mainly have established a few strong symbols for future generations of Cambodians, the vast majority of whom did not experience the terror of Pol Pot's regime and "that time of damned algebra", as French poet and resistance fighter during the Second World War René Char would have said.