In Ukraine, a large number of civilian casualties resulted from “attacks where explosive weapons with wide area effects were used” points out a UN report published on September 27 and covering the period from February 1 to July 31 this year. It documents abuses including “arbitrary deprivation of life, arbitrary detention and enforced disappearance, torture and ill-treatment, and conflict-related sexual violence”. This report came shortly after an interim one by another UN-appointed body, the Independent International Commission of Inquiry on Ukraine, whose chairman Erik Møse of Norway said that “war crimes have been committed”.

These two bodies operate separately and have different mandates, but are cooperating, according to Norwegian judge and former president of the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR) Møse. The three-person Commission of Inquiry which he heads was set up by the Geneva-based Human Rights Council in March 2022 to investigate alleged violations of human rights and international humanitarian law (IHL) in Ukraine and preserve evidence for “future legal proceedings”. The UN Human Rights Monitoring Mission in Ukraine was established in 2014, after Russia annexed Crimea. It “monitors, reports and advocates on the human rights situation in Ukraine, with a particular focus on the conflict area of eastern Ukraine and the Autonomous Republic of Crimea and the city of Sevastopol, Ukraine, temporarily occupied by the Russian Federation”.

Guilty verdicts

The Mission’s September report for the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR – also Geneva-based) points mostly to Russian abuses, but says it has also documented some on the Ukrainian side, particularly against prisoners of war. “OHCHR welcomes efforts of the Government of Ukraine to investigate and prosecute serious violations of IHL and gross violations of international human rights law perpetrated in the context of the armed attack by the Russian Federation, and to bring perpetrators to account,” says the report. “It also notes Government efforts to address violations perpetrated by its own agents and awaits concrete progress in this regard.”

It notes that since February 24, when Russia invaded Ukraine, “national courts of Ukraine have rendered guilty verdicts against six members of Russian armed forces and affiliated armed groups for violations of the rules and customs of war. One Russian serviceman was convicted of killing a civilian, and two servicemen were found guilty of indiscriminate shelling resulting in damage to civilian objects. In addition, three members of Russian-affiliated armed groups were prosecuted and sentenced for pillage of private property.” Justice Info has been documenting these trials through its correspondents in Ukraine.

The OHCHR report notes that Russia too has an “obligation to investigate, prosecute, and punish members of armed forces and affiliated armed groups found to have committed violations of IHL and international human rights law”, but that it is “not aware of any measures taken at the national level in the Russian Federation to hold its combatants or those in command to account for such violations”.

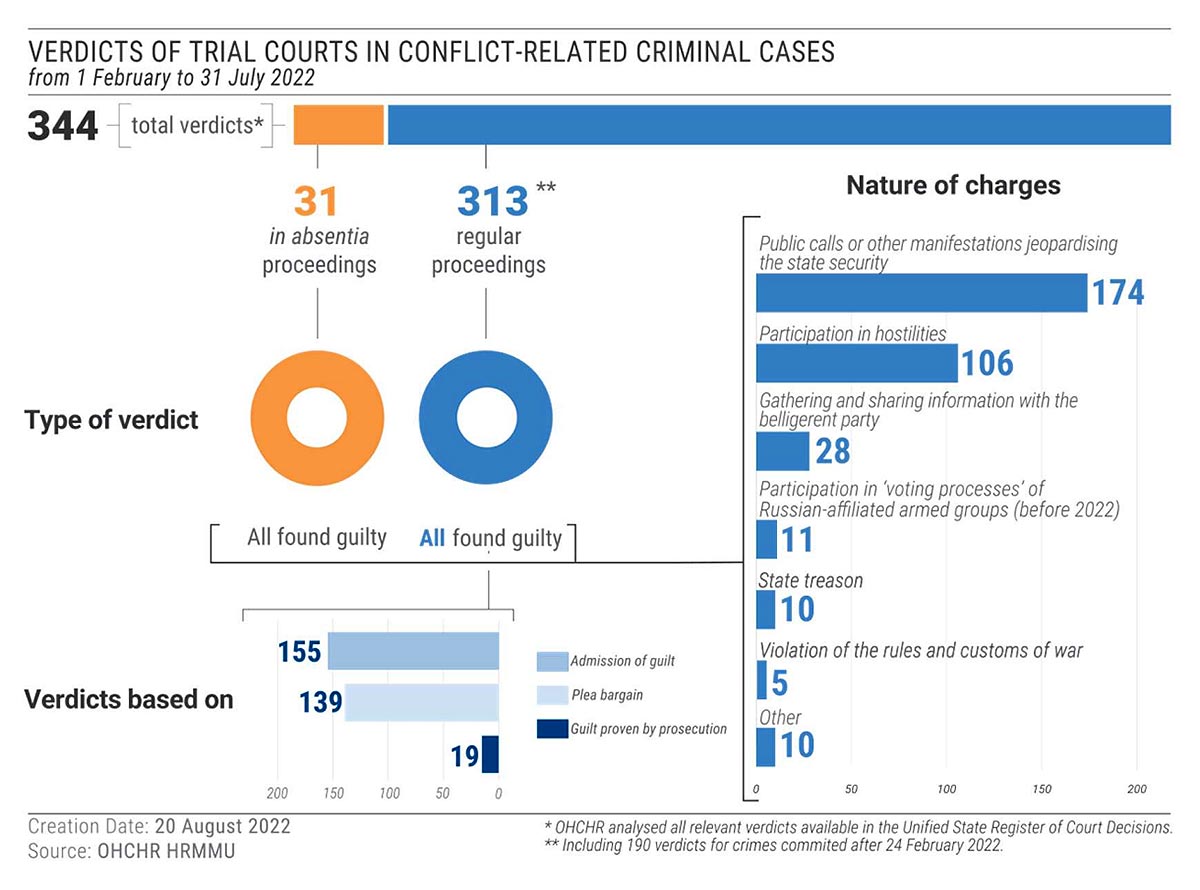

Ukraine clearly has the upper hand on justice. OHCHR says that during the reporting period it monitored 14 proceedings and analysed 344 verdicts, of which 190 verdicts for crimes committed after the Russian invasion on February 24 [see chart]. The report points to fair trial rights violations in separatist regions, including Donetsk, where a court handed down death sentences against three non-nationals who were members of the Ukrainian armed forces [subsequently released in a prisoner swap]. But it says OHCHR is also “concerned about recurring human rights and IHL violations in trials against members of Russian armed forces and affiliated armed groups” by Ukrainian national courts.

“Confessions under duress”

These include “violations of the right not to be compelled to testify against oneself or confess one’s guilt, and the right to prepare a defence”, according to the report, which does not specify the cases concerned. In such cases, it continues, prosecutors and investigators have offered defendants the possibility of release as part of a prisoner swap, in return for a confession. OHCHR says it is “concerned that this practice applies undue psychological pressure on defendants to accept an arbitrary offer and confess, regardless of their innocence or guilt”.

It notes that, prior to July, there was no legal basis for offering defendants to be exchanged, and “even after the procedure was formally established, there was no guarantee that a particular defendant would be included in any exchange”. It also documented “19 cases” in which it says defendants did not have the possibility to consult with their appointed lawyer prior to the trial. “We observed that at least 13 trials were conducted in what appeared to be ‘expedited’ proceedings,” the UN Monitoring Mission in Ukraine told Justice Info in written answers to our questions. “We also noted that national human rights organizations described such trials as ‘conveyor justice’. In those cases, defendants participated via videoconference. Preparatory hearings and hearings on the merits were also in some instances held in one day, and verdicts based mostly on admissions of guilt made during trial were rendered on the same or the next day. These proceedings raise concerns about the overall fairness of the trial, particularly in light of the fact that confessions were provided under duress.”

The Ukrainian parliament adopted a legal procedure on prisoner of war exchanges on July 28 this year, the report explains. Amendments provide that even prisoners of war accused of international crimes such as war crimes and crimes against humanity can be released from detention and exchanged, while the criminal proceedings against them continue in absentia. But OHCHR expresses concern that this might amount to a de facto amnesty and recalls that States “must investigate international crimes alleged to have been committed on their territory, and, if appropriate, prosecute suspects”.

Release of Shishimarin co-accused

While the report is not specific in terms of cases, it does mention concerns about one identifiable case covered by Justice Info: that of captured Russian serviceman Vadim Shishimarin, who was sentenced in May to life in jail after pleading guilty to killing a civilian – and eventually had his sentence reduced to 15 years on appeal in July.

In that case, the SBU [Ukraine state security services] published a defendant’s confession online prior to the trial, according to the report. “That defendant stood trial for killing a civilian, while his fellow servicemen, who may have given orders to kill the civilian, were released during an ‘exchange of prisoners of war’,” the report continues. “This may breach the obligation of Ukraine to investigate and prosecute war crimes, where appropriate. In addition, the defence lawyer was denied his request to question the released servicemen, which may have jeopardised the equality of arms. Lastly, the release and exchange of the servicemen may also jeopardize the realization of rights of victims to truth and reparations.”

“We have documented cases where the authorities have published confessions of defendants prior to trial, which violates the presumption of innocence”, the Mission stressed in its written responses to Justice Info. “In addition, defendants have been held in metal and glass boxes during the trial, which international human rights jurisprudence has found may jeopardized the presumption of innocence.”

Treason trials and trials of civilians

OHCHR “cautions that prosecuting for state treason individuals serving in Russian-affiliated armed groups and entitled to prisoner of war status is inconsistent with the principle of combatant immunity”.

The UN human rights body says it also followed criminal proceedings against civilians prosecuted for conflict-related crimes. During the reporting period, Ukrainian courts rendered 260 verdicts in such cases, against 261 persons (194 men and 67 women), according to the report. OHCHR says it documented “27 cases of arbitrary detention, enforced disappearance, torture, ill treatment of defendants and suspects in order to compel them to testify, procedural violations for house searches or arrests, and lack of access to legal counsel during the initial period of detention and interrogation”.

Defendants from Russian-affiliated armed groups captured after February 24 were sentenced to prison terms ranging from 11 to 15 years for trespass against territorial integrity, state treason, membership in a terrorist organization, membership in unlawful armed formations and unlawful possession of firearms. “IHL does not explicitly prohibit the prosecution for state treason of combatants who defected. However, sentencing members of Russian-affiliated armed groups in the hostilities under the above-listed crimes for acts that constitute mere participation in the armed conflict violates their combatant privilege,” said the Mission.

Cooperation with the ICC

As well as investigating and prosecuting crimes at national level, the report notes that the Ukrainian government is also cooperating with various international bodies that can contribute to accountability, including the International Criminal Court (ICC).

However, OHCHR writes that an explanatory note to the law on cooperation with the ICC, adopted by the Ukrainian parliament on May 3, restricts its scope to the investigation and prosecution of only people fighting for Russian armed forces or affiliated armed groups. “Therefore, the cooperation of the International Criminal Court with Ukrainian judicial authorities in cases of alleged crimes committed by individuals fighting on the side of Ukraine remains outside the scope of the law and unregulated,” says the report. “This may have a serious impact on the right to effective remedy for all victims of international crimes, regardless of the perpetrator.”