This Monday, January 16, 2023, the Court of First Instance of Tunis was expecting a busy day. The morning was to see the call to the bar of Imed Trabelsi, favourite nephew of Leyla Trabelsi Ben Ali, wife of the deposed president Zine el-Abidine Ben Ali. He was brought from the prison where he has been languishing for 12 years to appear in a corruption case. Then was the scheduled hearing of Taoufik Baccar, former governor of the Central Bank from 2004 to 2011. Other important cases were also to be examined.

However, taking three and a half hours from 10am to 13.30, the president of the specialized criminal chamber of Tunis postponed the 16 cases of the day to April 3. They are all as complex as each other, and many have been open for nearly five years. Some deal with serious violations of human rights, including the story of Hedi Boutib, an Islamist student killed in 1990 by the university police, and the case of the Tunisian Jewish community, on grounds of discrimination in the field of health. But the majority of the crimes relate to financial embezzlement, corruption in the banking sector and misappropriation of public property involving Ben Ali's family, his allies and the businessmen in his inner circle.

The court president’s adjournments respond to the requests of the defendants’ lawyers, those of the civil parties or to the requests of the State legal department head, otherwise it was the judge herself who noted the absence of the lawyers of some victims or defendants. The judge announced additional hearings in camera in the case of wealthy businessman Chafik Jarraya, also brought from prison where he has been since 2017. But neither the representatives of the Jews of Tunisia, nor the family of Hedi Boutib attended this hearing. In reality, the judicial process of the post-dictatorship in Tunisia is dragging on, threatened by a clear desire to bury it. Not many people believe in it any more.

Delaying tactics

None of the 205 cases investigated by the Truth and Dignity Commission (IVD), inaugurated in May 2018, transferred to the 13 criminal chambers specialized in transitional justice has so far resulted in a verdict. They involve 1,746 alleged perpetrators. The difficulties of this obstacle course frustrate and even cause despair for the majority of victims. For Sihem Bensedrine, former president of the IVD, "opening all the files at once leads nowhere. The incessant postponement amounts to a denial of justice for the victims".

In a report published in December 2020, several national and international organizations including the Association of Tunisian Magistrates, the World Organization Against Torture and the International Commission of Jurists, denounced work overload of the magistrates of these chambers who must, devoid of any logistics, also deal with ordinary justice cases. They noted that the method of appointing judges by annual rotation disrupted the work of these bodies, transferred experienced judges to other jurisdictions and led to long delays between hearings, sometimes up to six months, while the quorums of judges in the specialized chambers were constituted.

"On the side of the accused, they are continuing delaying tactics so as to extend the trial time in the hope that President Kaïs Saïed publishes a decree cancelling the existence of specialized chambers. For nearly five years, they have been relentlessly using blocking tactics: either the defendant does not appear before the court, or his lawyer is not there," says Hamza Ben Nasr, transitional justice coordinator at the NGO Lawyers Without Borders. At the January 16 hearing, the State legal department head, who defends the State's economic interests in court, and several lawyers for the defendants did ask several times for a postponement of the hearing to examine and respond to the cases, but the victims' lawyers did not seem ready either to plead and move the process forward.

Weaknesses among victims' lawyers

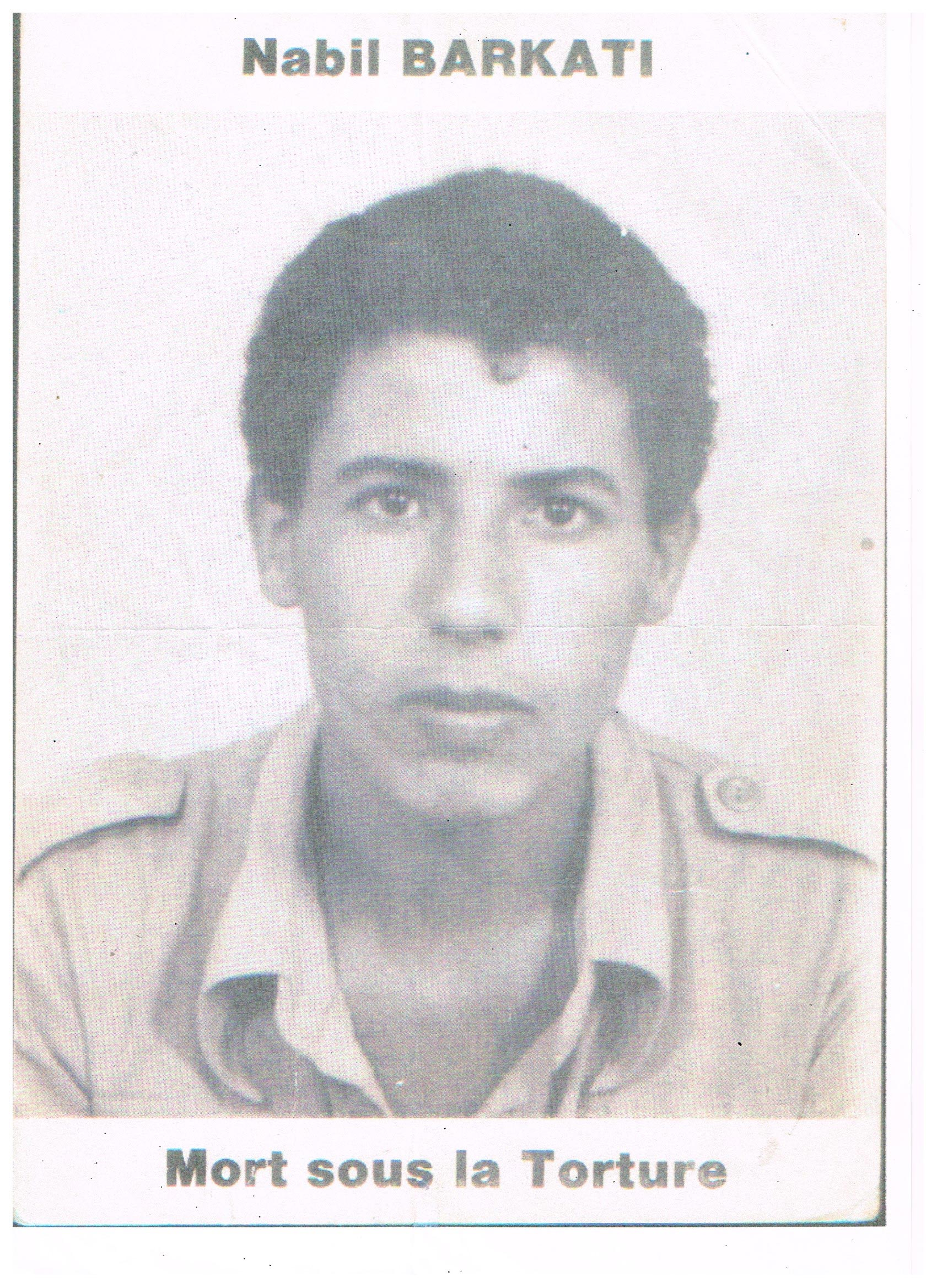

Even when magistrates declare they are ready to hear the lawyers’ pleas, the latter do not respond. For example, the president of the specialized chamber of Kef, 175 km west of Tunis, announced last April to the heirs of Nabil Barakati, a trade unionist and extreme left-wing activist assassinated in 1987, that she was reserving the next hearing for pleadings. But the lawyers for the civil parties were not ready to present their final arguments.

Most of the men and women defending victims of gross human rights violations work pro bono and have also seen their passion for the process wane over the years. "Some have not even consulted the indictment files prepared by the IVD," says Hamza Ben Nasr. The defendants, on the other hand, call on the most experienced professionals of the Bar -- paid lawyers, who are now claiming reparations for their clients for all the "inconvenience" suffered during this judicial marathon.

Elmy Khadri, president of the association Al-Karama for rights and freedoms and himself a former victim under the dictatorship, does not miss any hearing of the specialized chamber of Tunis, and improvised as a journalist to report on the various cases, combing the country to follow their progress. "There is no coordination between the lawyers [of the victims],” he says. “On the other hand, the torturers' lawyers seem to work together and present arguments along the same lines. They all contest, for example, the existence of the specialized chambers since the new Constitution deleted any mention of transitional justice. However, they know that the law organizing transitional justice remains in force.”

Sihem Bensedrine is convinced that most of the civil parties’ lawyers do not know the specificities of transitional justice, confusing its foundations with those of ordinary justice. "Reparation is not the competence of the specialized chambers. It is the Dignity Fund that is responsible for compensating victims on the basis of reparation decisions issued by the IVD. Such a request by the lawyers [before the specialized chambers] only plays an additional role of slowing things down," she laments.

Institutional bottlenecks

"Specialized criminal chambers also face difficulties in investigating cases of corruption and embezzlement of public funds because of the time these cases require and the lack of expertise in the field of criminal business law," five United Nations rapporteurs working for the UN Human Rights Council wrote to the government in February 2021.

In fact, the judges of the specialized criminal chambers have faced several sources of adversity: the police unions, which asked members accused in cases of torture not to respond to IVD summonses; the Ministry of Justice, which has never provided a salary with bonuses and benefits commensurate with the workload of the specialized chambers judges; and the Supreme Council of the Judiciary, which has continued to transfer judges from one court to another at the beginning of each judicial year.

Tunisian judges now work in an extremely hostile political environment, especially since the country’s president, who has full powers since he suspended parliament in July 2021 and rules by decree, has been waging a merciless war against the judiciary. On June 1, 2022, he issued a decree dismissing 57 judges on summary charges of corruption and obstruction of investigations. On March 20, he also passed a decree-law on criminal conciliation that amounts to an amnesty for businessmen accused of economic and financial crimes, according to several NGOs working on transitional justice, including Lawyers without Borders (ASF). This decree-law is intended to remove corruption crimes from the specialized chambers and from all other jurisdictions.

"Kef is our lifeline"

The president of the Kef specialized chamber has just set the next hearing in the case of Nabil Barakati for January 27, several months after announcing that she had completed her hearings and interrogations and was ready to pronounce a verdict. Nabil's brother Ridha Barakati is running here and there to mobilize his lawyers. Three of the 40 lawyers who attended the opening of this trial on July 4, 2018 are now putting the final touches to their arguments.

"Kef is our lifeline, our last chance,” warns lawyer Ilyes Bensedrine, a legal adviser to ASF and former deputy director responsible for investigations at the IVD, “because no one can guarantee that the president of the chamber won’t be transferred in a future rotation of transitional justice judges, nor that the President won’t issue a decree-law to cancel these judicial structures." A first plea followed by a first verdict could perhaps rekindle the flame of Tunisian transitional justice and encourage other magistrates to pronounce long-awaited judgments.