With no more inmates, Arusha’s white elephant handed its prison over to the Tanzanian government. The UNDF (United Nations Detention Facility), which consists of 89 high-security cells in a Tanzanian prison next to the Arusha airfield, eight kilometres from the city centre, has housed more than 93 prisoners in its 27 years of existence, according to figures provided by the registry.

When it opened in 1996, under the jurisdiction of the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR), it was the first time a United Nations body had established and operated a detention facility. After the ICTR closed in 2015, the prison was placed under the responsibility of the International Residual Mechanism for Criminal Tribunals Mechanism (IRMCT). It was this “Mechanism” that handed it over to the Tanzanian government in a small ceremony at the UNDF on February 23, which Justice Info attended.

Mechanism registrar Abubacar Tambadou, in a grey suit and red tie, represented the United Nations Secretary-General. The Commissioner General of Prisons, Ramadhan Nyamka, represented the government of Tanzania, wearing a brown and gold uniform. The government will take possession of the facility on February 28, the UN official said. This will help to "relieve the pressure on the national high security prisons in one way or another," the Tanzanian military official said. Under the Arusha sun, above a table covered with the UN flag, the two men symbolically exchanged a handshake on the official handover of the prison for those accused of the 1994 genocide.

May 26, 1996: the first three inmates arrive

This is also the death certificate of a detention centre that came to life on May 26, 1996 with the arrival of its first three Rwandan residents: Jean-Paul Akayezu, ex-mayor of Taba in the former prefecture of Gitarama; Clément Kayishema, a doctor and former prefect of Kibuye; and Georges Rutanganda, former vice-president of the Interahamwe militia which spearheaded the genocide of Tutsis in Rwanda.

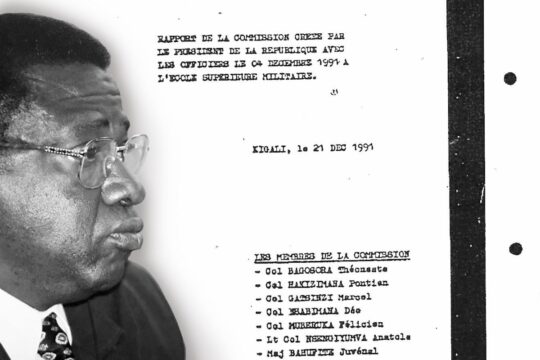

After them, more than 90 other ICTR defendants followed in these cells, including high-ranking army officers, ministers including Jean Kambanda who was the first Prime Minister during the genocide, religious leaders, but also more ordinary people such as militiaman Omar Serushago or a certain GAA - whose identity remains protected. GAA, a farmer and the only Tutsi to be tried by the ICTR, was charged with contempt of court.

Kambanda spent only a few days there, before entering into negotiations with the prosecution for a guilty plea that nevertheless resulted in a life sentence. The banker turned politician, after being approached by the prosecutor's office, was moved to a safe house in Dodoma, in the centre of the country.

A good commander and a “good life”

History does not say whether Kambanda enjoyed better conditions of detention. But for those who remained in the UNDF, life was good. They ate well, played sports, worshipped in their respective religions, and celebrated festivals within the prison. Over time, they were able to have conjugal visits. The former residents and their lawyers attribute these good detention conditions to two men in particular: former ICTR registrar Adama Dieng and above all Saïdou Guindo from Mali, the commander who administered this prison for 18 years, from 1999 to 2017.

"He was very kind," Innocent Sagahutu says of Guindo, who died on December 22, shortly after his retirement. "He was fraternal and friendly, and he listened carefully to our grievances," the former Rwandan captain told us by phone from Niamey, Niger, where he is stranded with seven others from the ICTR. Peter Robinson, an American lawyer who visited the prison from 2002 to 2010 to speak with his clients, agrees. He went to talk to Joseph Nzirorera, ex-secretary general of the former presidential party, and then visited for three years to defend former planning minister Augustin Ngirabatware, the last inmate of the UN prison. Ngirabatware, son-in-law of Félicien Kabuga (whose trial is underway in The Hague), left Arusha last December for Senegal, where he is serving his sentence.

“Their conditions inside the UNDF were quite good, they had their freedom of movement in the Detention Facility, they lived relaxed compared to those in the UNDU in The Hague where security is very tight,” Robinson told Justice Info by telephone from the United States. “Yes, it is true that in The Hague they have a better facility in terms of infrastructure, but concerning life itself, the conditions were much better at the UNDF. They lived in community. People from all levels of life, highly educated people with very poorly educated people but they lived in harmony, so to speak. They had representative committees for administrative matters, they were organized and lived well, even if a prison is still a prison.”

Worship in prison and Ngeze’s excommunication

Officers of religion paid by the ICTR and then the IRMCT visited the prison to officiate at the detainees’ various religious services. The Catholics, who were more numerous, had a succession of chaplains, even though they had priests amongst them such as Athanase Seromba, Hormisdas Nsengimana and Emanuel Rukundo. "Before the UNDF extension, there was a large room that could be used for meetings and as a chapel for the celebration of masses. But when they built and added a level, the space was reduced, and what was used as a refectory could also be used as a chapel on Sundays," explains Sagahutu, who arrived in the building in November 2000. The former composer of the Kigali choir, former MRND president Matthieu Ngirumpatse, led a choir in the prison that made mass very enjoyable, according to former soldier Sgahutu. "We had a big choir that could make the angels descend at Christmas or Easter," he joked.

The Anglicans lost their bishop Samuel Musabyimana, who died in 2003 before his trial. But they regularly received an outside pastor, who might at times give way to Justin Mugenzi, a religious leader of lower rank than Musabyimana who "said he was a canon", according to Sagahutu.

The Adventists, notwithstanding the presence of Pastor Elizaphan Ntakirutimana, had a pastor who came every Saturday for Sabbath. And like the Anglicans, they celebrated their masses in the language classrooms. As for "the Muslims, for whom I was responsible, I managed to have a room set up for us to use as a mosque. We had an Imam who came twice a week, and who ended up getting a job at the prison," says Sagahutu. He revealed that in 2001 he found himself obliged to "excommunicate" Hassan Ngeze, the prison troublemaker, after the former editor of extremist newspaper Kangura declared himself a follower of Satan.

Healthy spirit and body

The UNDF tenants were also well off when it came to earthly sustenance. "They had good, fresh food, unlike those in The Hague," says Robinson. "African food, appropriate for each of them." And Sagahutu says "the two chefs who succeeded each other at the UNDF had exceptional culinary skills”. The inmates ate three times a day, and special attention was paid to each person's diet. "On feast days, we could dip into our pockets to add, for example, goats for grilling and drinks," recalls Sagahutu. “For strong drinks, even though it was forbidden, we had our means to get them," he confides. A retired Tanzanian security officer, who requested anonymity, confirmed this. The UNDF did not escape petty corruption, it seems.

But a healthy body does not come without sport. The UN prison facility had a modern gym, equipped with various machines and weight training equipment, which allowed them to row in the air, run without a destination, cycle on the spot. The inmates followed one another into the room in groups of five to ten, depending on the prison population at the time - which reached its peak in 2004 with 53 residents. Pauline Nyiramasuhuko, the only woman indicted by the international tribunal, naturally had a gym group all to herself. At the entrance to the room, a notice determined which groups could use the gym when.

Conjugal visits allowed

After repeated requests from the detainees, the ICTR authorized conjugal visits as of May 2008. A room was set up for this purpose. Each detainee was entitled to three hours of visits with his or her spouse every two months. However, if the spouse lived outside Tanzania and neighbouring countries, the spouse could repeat the visit once within a shorter period. At the time, Saidou Guindo explained to the press that "nothing prohibits conjugal visits at the international level" and that "for convicted prisoners, it is the prisoner who is punished and not his wife. For detainees whose trials are underway, there is always the presumption of innocence. We have a duty to make detention more humane".

"We had asked that for the single men, we look for girlfriends in town, but this was refused, surely because of Kigali," says Sagahutu. Rwanda had indeed criticized the decision to allow conjugal visits. Martin Ngoga, then Rwanda's attorney general, reacted angrily to the ICTR's announcement, calling the decision "ridiculous”. Since this practice is not common in Rwanda, the country feared that this decision would become a reason not to authorize transfers to its territory. However, some ICTR detainees were subsequently transferred to Rwanda.

Ngeze the UNDF troublemaker

Certainly, the UNDF would have been calmer without the presence of Ngeze. The self-proclaimed journalist gave the prison management a hard time more than once. First of all, there was a "suicide attempt". In January 1998, he allegedly took a mixture of chemicals, apparently with the intention of killing himself. According to some sources, Ngeze had asked his fellow inmates about an antidote, cow's milk, which he rushed to drink when he regained consciousness.

In 2001, there was the case of his website. On "www.hassanngeze.s5.com", Ngeze talked about his trial and about life in the ICTR prison in Arusha, which was all illegal. A thorough search of his cell by ICTR security guards and computer technicians uncovered only a modem that was plugged into his computer but not connected. There was a hypothesis that he was using a radio with a WorldSpace-type mini-antenna. The mystery was not solved by the administration, but the "journalist" stopped his publications.

Faced with his frequent mood swings, whether in prison or in court, Ngeze's lawyers at one point requested and obtained a psychiatric examination of their client. The results have not been made public. His fellow prisoner Sagahutu believes that he was not sick, but that “he was a very intelligent person despite his level of education”. According to Sagahutu, "Ngeze was ahead of all of us: he had a website, whereas some of us even today don't know how it works".

Swahili and English classes

"This guy [Ngeze] was very intelligent, I had the opportunity to talk to him and I was surprised to learn that he hadn't been to school," said Cleophace Sotera, who taught language classes at the UNDF. He explained that there were two classes, one for English and one for Swahili. "These people were very diligent, although sometimes class time was a way to relax. They even asked for language certificates from the United Nations, but to no avail. They were good guys, very jovial, full of humour, as if they had gotten used to prison life," he recalls. "But one time I asked Captain Sagahutu, 'How are you doing?' and he said, 'I don't know', and that got me thinking."

Most of the people who dealt with the UNDF detainees say they have good memories of them, with the exception of one female security officer who spent more than 20 years there. She says she had a lot of trouble dealing with them, but did not want to go into details.

One of the nurses who had to take care of them confided that "for us who are not judicial staff, these people seemed very good. We made friends with them, we had uncles, brothers, grandfathers. We were very sad when some of them died, like bishop Samuel Musabyimana, the old pastor Elizaphan Ntakirutimana, Joseph Serugendo, or another one who was said to be very rich in Rwanda, Joseph Nzirorera." This Tanzanian nurse remembered their Rwandan names perfectly. "Also those who died living at the safe house, like old Joseph Kanyabashi and Jerome,” she says. “I even visited Jerome Bicamumpamka when he was hospitalized in Nairobi, not as a nurse, but as a sister."

Miriam Mpogole was the courier who brought them documents, and lost her job when the detention centre closed. With the life of the prison ending, so have the jobs of locals and internationals working there. "Often they could get up in a bad mood,” says Mpogole. “You bring someone a document to sign, you greet him, he looks you in the eye and doesn't answer, signs the document and gives it to you without a word. The next day when you see him, he welcomes you with warmth..."

A wrongly accused

But this prison has not only housed alleged perpetrators of the Rwandan genocide or people accused of contempt of court. During Operation Naki (Nairobi-Kigali), which saw the arrest of people in a large-scale net operation launched by the ICTR in the Kenyan capital, a young Rwandan trader mistaken for Nyiramasuhuko's son Arsène-Shalom Ntahobali by the ICTR tracking team and Kenyan police officers was arrested on July 18, 1997. Esdras Twagirimana left the UNDF on October 20, 1997 without compensation, after the real Ntahobali was arrested.

But apart from this mistake, which was not its fault, the UN prison service respected international standards. The hunger strikes at the detention centre were not about living conditions but about what its inmates felt were denials of justice in the conduct of their trials. A plaque will remain on the site for posterity: “With gratitude from the United Nations for the partnership with the government of the United Republic of Tanzania for the use of this detention facility – 20 May 1996 to 28 February 2023.”