Can French justice try crimes against humanity and war crimes committed in Syria in the name of universal jurisdiction? This is the thorny question that the Court of Cassation will have to decide on March 17. This hearing is so crucial that the public prosecutor, François Molins, has asked that it be carried out in plenary session - the most solemn formation of the Court, which is only called upon to decide important or novel questions. At issue are the ambiguities of the 2010 law integrating French universal jurisdiction over international crimes into the penal code, which reflect political reluctance to develop such litigation in France.

"Originally, the bill tabled by the Ministry of Justice did not even include provisions for universal jurisdiction," recalls lawyer Simon Foreman, former president of the French Coalition for the International Criminal Court (ICC). In 2006, the bill tabled by the minister's office only sought to integrate the Rome Statute, the ICC’s founding treaty ratified by France in 2000, into the French penal code. "With several human rights organizations, we convinced the senators of the Law Commission to add provisions enshrining France's universal jurisdiction to judge the offences of the Rome Statute," Foreman recounts.

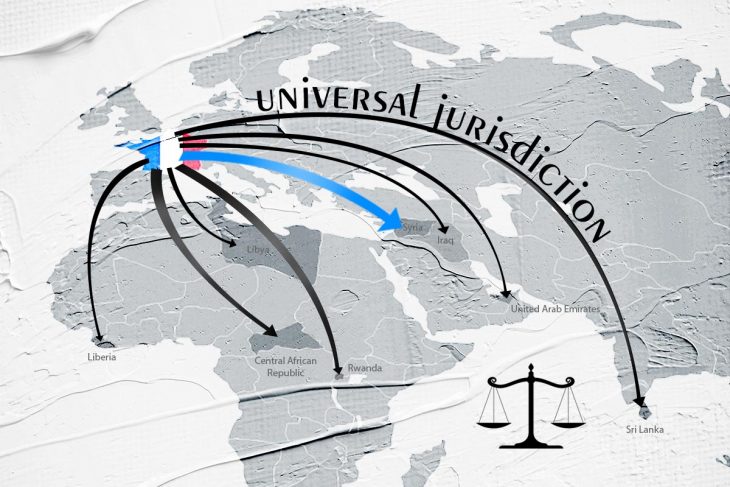

In France, universal jurisdiction - under which a State can prosecute alleged perpetrators of serious crimes if they are present on its territory, regardless of where the crimes were committed and regardless of the nationality of the suspects and victims - already existed in matters of torture, but not in cases of crimes against humanity, genocide and war crimes. However, the preamble to the International Criminal Court Statute states that "it is the duty of every State to submit to its criminal jurisdiction those responsible for international crimes", while Article 1 of the Rome Statute establishes a principle of complementarity between the court based in The Hague and national jurisdictions, note the senators, who added an amendment to the bill. "The ministry, which had not anticipated this at all, was caught off guard," Foreman recalls. In order to defeat the amendment, the cabinet in which Justice Minister Rachida Dati served added in a hurry its own provisions enshrining the universal jurisdiction of French courts but attached several conditions.

The 2010 law’s restrictions

The first restriction reserves prosecution for the public prosecutor only. Victims can certainly file a complaint and may eventually be accepted as civil parties. But only the prosecutor's office has the power to refer a case to an investigating judge and initiate proceedings, whereas victims have this right for other crimes. "At the time, French politicians feared being overwhelmed by diplomatically embarrassing investigations," explains lawyer Clémence Bectarte, who represents the International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH) in one of the cases being examined by the Court of Cassation on March 17. "Everyone was talking about the consequences of Belgian universal jurisdiction. Introduced in 1993, this made it possible not only to initiate proceedings on the basis of civil party complaints but also proceedings in absentia, i.e. in the absence of the accused. A series of complaints against Augusto Pinochet, Fidel Castro, Ariel Sharon and others followed, leading to such diplomatic headaches that Brussels ended up limiting its jurisdiction in 2003.

The second condition is that the public prosecutor must ensure the suspect is not being prosecuted by the ICC or another competent state. Above all, the 2010 law states that, in order to be prosecuted, the suspect must not only be present in France but also have his or her "habitual residence" there. "The executive didn't want us to start arresting senior Saudi or Emirati officials who come to do their shopping on the Champs-Élysées," storms Senator Jean-Pierre Sueur, who has been fighting for years to remove these conditions from French law, "but most war criminals are not in their garden in Bécon-les-Bruyères (leafy Paris suburb) growing tulips!"

But it is the fourth condition that now threatens more than a third of the current investigations for war crimes and crimes against humanity in France: that of “double criminality”. On November 24, 2021, the Court of Cassation, which had been seized by the defence of Syrian suspect Abdulhamid Chaban, ruled that French justice could not prosecute him, because the "crimes against humanity" of which the Syrian is suspected do not exist in Syrian law. Indeed, since the law of 2010, the criminal code specifies that these crimes - as well as war crimes - can only be prosecuted "if the acts are punishable by the legislation of the State where they were committed, or if this State or the State of which the suspected person has the nationality is a party to the convention [giving rise to the ICC Statute]" - a condition removed in 2019 for the crime of genocide only.

Damascus having never ratified the Rome Statute and the Syrian penal code not mentioning crimes against humanity, this condition of "double criminality" is not met and the French courts are therefore incompetent, the court decided.

Snowball effect

In the wake of this decision, France's universal jurisdiction over war crimes is being challenged, on the same argument, by the defence of Syrian Majdi Nema. Arrested and indicted in January 2020 for war crimes, this former spokesman for the Syrian Islamist group Jaish Al-Islam ("Army of Islam") is suspected of "torture or acts of barbarism, enforced disappearance, war crimes and participation in a criminal association for the preparation of a crime or a war crime”. The argument is that French justice is not competent to judge the "war crimes" of which he is accused, as these are not qualified in the Syrian penal code.

On the question of “double criminality”, there are two opposing interpretations," says Bectarte. “And until the November 24 ruling, the issue had not been decided by the Court of Cassation, as no case of crimes against humanity or war crimes committed after 2010 had been brought before it.” In the Chaban case, the interpretation of the investigating chamber - which was that of the specialized unit on international crimes at the prosecutor's office - was that the condition of double criminality was respected, because while the Syrian penal code does not expressly refer to "crimes against humanity", the offences constituting these - murder, acts of barbarism, rape, violence and torture - are indeed condemned by Syrian law. The Court of Cassation replied that this was not the case because crimes against humanity, as defined in French law, are "necessarily committed in execution of a concerted plan against a civilian population group as part of a widespread or systematic attack". Therefore, in order for the condition of “double criminality” to be fulfilled, Syrian law would necessarily have to include "a constituent element relating to an attack launched against a civilian population in execution of a concerted plan". In short, it must condemn "crimes against humanity".

Risk taken by the specialized prosecutors

"The November 24, 2021 ruling came as a real surprise, because of its restrictive interpretation," says Aurélia Devos, Deputy Prosecutor in charge of the specialized prosecutors’ unit from 2012 when it was set up until 2021. "It was unthinkable for us that such a restrictive interpretation of the law could be retained. In the absence of jurisprudence, this being a new case, we adopted an interpretation that prevails in extradition matters and which was followed by the trial chamber". This interpretation is much more flexible.

However, as early as 2010, several human rights organizations such as Amnesty International had warned of the risks of a restrictive interpretation of this “double criminality”. Bectarte points out that the issue had been raised several times in parliamentary debates. On July 13, 2010, when asked about “double criminality”, the rapporteur of the bill, Thierry Mariani, stated: "This condition is never just a translation of the principle of legality of sentences. […]. On the other hand, it does not imply that the acts must be incriminated in the same way in both States. The acts must indeed be punished in the other country even if they are qualified differently or if different penalties are applied.” Meanwhile State Secretary for Justice Jean-Marie Bockel tried to reassure: "No serious act, be it genocide, murder or rape, will escape the jurisdiction of French courts because of this requirement of double criminality; everyone is aware of this. There is no risk."

"We did not feel we were taking a "risk" by favouring this interpretation, because in so doing we were placing ourselves as close as possible to the spirit of the law," explains Devos, who points out that at each opening of an investigation, a search for compliance with the criteria - including that of double criminality - was carried out and validated by the public prosecutor. “The notion of a ‘concerted plan’ in the context of crimes against humanity was, in our view, a mere formality, since the very scope of such crimes implies that they cannot be improvised," she continues. “To demand that this notion be taken into account in the condition of double criminality is to empty the law of its substance.” For France is the only country to include this notion in its definition of crimes against humanity. "So it would simply mean that we do not have universal jurisdiction over crimes against humanity, except for crimes in Rwanda and former Yugoslavia," concludes the former prosecutor.

The fears of political leaders

Eleven years later, however, the Court of Cassation ruled against the prosecution. Although the decision is not final (the FIDH objected to the ruling on the grounds that it had not been notified of the appeal), it nonetheless caused a small earthquake in the world of judges and specialized investigators. So much so that the Ministries of Justice and Foreign Affairs issued a joint statement on February 9, 2022: "Our ministries will follow closely the next court decisions to be taken," they declared. “Depending on these decisions, our ministries are ready to rapidly define the changes, including legislative changes that should be made in order to allow France to continue to resolutely pursue its commitment against impunity for international crimes.” This promise seems to be lip service and please no one in the ministries.

"I think there is an irrational fear, based on a misunderstanding of what universal jurisdiction is, that is still deeply rooted in the ministries," says Foreman. The incursion of the judiciary into the discreet world of diplomatic relations is frightening them, the lawyer says. And while the Court of Cassation ruling is disturbing - so much so that it confronts France with its contradictions between its stated commitment to fight impunity for Syrian crimes and the inability of its justice system to bring these crimes to trial -, the government seems unenthusiastic about the idea of changing the law -- perhaps because further debate would call into question not only double criminality but also the other conditions of universal jurisdiction. A bill calling for the suspension of four restrictive conditions, although introduced by member of the parliamentary majority Guillaume Gouffier-Cha, has been stalled in the National Assembly since last June.

A crucial issue

For the prosecution, the outcome of the March 17 plenary session is crucial. In addition to the condition of double criminality, the Court will also have to specify the contours of two other conditions of French universal jurisdiction.

Majdi Nema’s defence believes that since the International Criminal Court has not explicitly declined jurisdiction, one of the conditions for universal jurisdiction is not met. This argument does not hold, according to the investigating chamber which deemed that the ICC does not have jurisdiction over Syrian crimes, Damascus having never ratified its Statute. The Court of Cassation will have to decide.

But it is mainly on the condition of habitual residence that the Syrian's defence is also challenging French jurisdiction. Majdi Nema having been present in France for only the limited time of a study period, it argues that this condition is not met.

Finally, on the accusations of torture and enforced disappearance against the suspect, the Court will have to define whether they are applicable to a non-state group. French universal jurisdiction in matters of torture is based on a convention, the New York Convention of 1984, which was signed between States and is therefore explicitly binding on them. Can the jurisdiction resulting from this convention be applied to non-state groups (which are therefore not parties to this convention)? This is the other debate that the French high court will have to decide.

Beyond the crucial issue of double criminality, the French Supreme Court will have to clarify the contours of many elements of French legislation on international crimes on March 17. The two judgments, concerning the Chaban case and the Nema case, will be handed down on May 12.