"Fuck! This country should not exist! And we will do everything to make it disappear." This is what Anton Kuznetsov-Krasovsky, journalist and presenter of the Russian TV channel "RT" (previously called "Russia Today") said early 2022, as shown on a video released on YouTube.

On April 15, 2022, Krasovsky also wrote a post on his Telegram channel "Anton Vyacheslavovitch", commenting on a video allegedly showing the shelling of the Russian city of Belgorod. On April 14, 2022, the governor of Belgorod had reported that two villages had been bombed from Ukraine. "Guys, it's obvious that you need to pull yourself together. Focus. Stop thinking about 'brothers'. They are not our brothers. I grew up there, I know what I'm talking about. Wipe out! Go ahead! Enough!" Krasovsky wrote.

On February 13, 2023, the Shevchenkivskyi District Court of Kyiv sentenced the Russian journalist in absentia to 5 years in prison with confiscation of property. Anton Krasovsky was found guilty of two crimes - public incitement to overthrow the constitutional order in Ukraine and distribution of materials urging such actions through the media, as well as public incitement to genocide, production and distribution of materials urging genocide.

“There is no Ukraine, this is our Russian land”

According to the court expert's conclusion, the video contains linguistic signs of propaganda for the elimination of independent Ukraine. It also advocates the uniqueness of the Russian people and national hatred. The conclusion of the semantic and textual expertise states that the words « wipe out » here meant "kill". The expert finds that there are grounds to assert that the publication contains a public appeal for the deprivation of life (physical destruction) of the Ukrainian people.

During the court hearing, video recordings of Krasovsky's speeches were played, in which he made offensive statements about Ukrainians, their nationhood, language and culture. A video also circulated on Telegram in which the accused is thanking Ukrainians for opening a criminal case against him, calling it a wonderful gift.

In another video in January 2022, in response to the host's suggestion that Georgia and Ukraine could join NATO, Anton Krasovsky said that in such case Russia would send in its troops: "We will send troops to Ukraine. This is our land. Take that! Screw you instead of NATO. Don't even dream about it, you scum!" When the host reminded him that the Euro-Atlantic direction of Ukraine's foreign policy is stipulated in the Constitution, Krasovsky shouted: "We will take your constitution away from you... We will burn it on Khreshchatyk with you by your own fire, just the way you like it. On burning tires... There is no Ukraine, this is our Russian land. No kind of Ukraine will ever resolve anything there... Russia will take the legally rightful Russian lands, so-called Ukraine... given to the Ukrainians by Stalin... Stalin created your Ukraine! There should be a huge statue of Stalin in every city of Ukraine."

State-appointed defense lawyer Andriy Kubov said that he never spoke to Krasovsky who has not approved the defense position. He said he believes that the evidence in this case is only the prosecution's assumptions, and that there is no clear evidence or direct access to the video files, so the video materials presented in court could have been distorted. He did not ask to acquit the accused and said that he was relying on the court's judgment.

Incitement or hate speech?

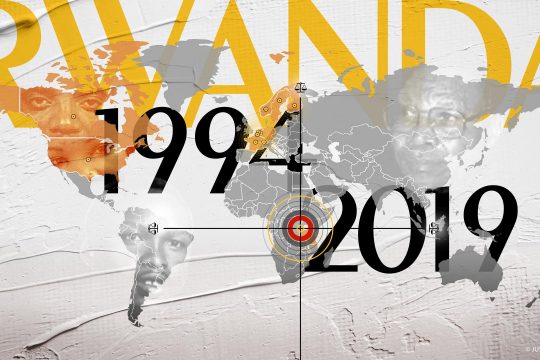

The great contemporary precedent for prosecuting journalists for incitement to genocide is the media trial at the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR) some 20 years ago. Ferdinand Nahimana, former director of Radio-Télévision des Mille Collines (RTLM) in Rwanda, Jean-Bosco Barayagwiza, a member of the radio's management committee, and Hassan Ngeze, former director of the newspaper Kangura, were convicted for the role their media played in the 1994 Tutsi genocide.

"In terms of international criminal law, it is direct and public incitement that is considered," said Jean-Marie Biju-Duval, who was Nahimana's lawyer. He points out that during the preparatory debates for the international convention on the prevention of genocide, in 1947-1948, one of the issues at stake was: do we include hate speech that can result in a crime? It was the Soviet Union that wanted to include it and the Western countries that were wary of a definition that was too broad and could be used as a means of repression by authoritarian regimes. "This was clarified by the media trial," explains Biju-Duval. "In the first instance, the judges had considered that RTLM's broadcasts before 6 April [the date on which the genocide was triggered] constituted incitement to genocide. The appeal chamber went back on that. It said that it was the call to murder [after that date] that constituted incitement, not the fact of having said 'you are subhuman'. Before [6 April], it's hate speech.”

In sum, hate speech can be criminalised but it does not necessarily constitute direct and public incitement. "It can be punished under domestic law but it is not an international crime," Biju-Duval said.

The French lawyer comments only cautiously on the case of Anton Krasovsky, as he does not have all the elements of the case. "Is it Ukraine which is targeted as a sovereign country or is it its nationals, i.e. the Ukrainian people? In this case, the first condition is met. And if you call for the murder of this group, then you are not far from direct and public incitement," he explains.

Before the ICTR, Biju-Duval recalls that the basic jurisprudence on the subject was that of the Nuremberg Tribunal, where the Allies tried Nazi Germany. Two of the defendants were former journalists: Hans Fritzsche, former head of news at the Propaganda Ministry, and Julius Streicher, former editor of the violently antisemitic newspaper Der Strümer. Fritzsche was acquitted while Streicher was sentenced to death. In the end, from Nuremberg to the ICTR, the dividing line between what constitutes an international crime and what constitutes hate propaganda has remained roughly the same. And like all such cases against journalists, the Krasovsky case will be analysed and debated along this same criminal line.