Opening last week’s hearings before the Yoorrook truth commission in Melbourne, southeastern Australia, Commission chair Eleanor Bourke reflected on the “historic moment” of an Aboriginal-led inquiry “asking questions to people in positions of authority, people who should be accountable about why things have happened and how certain policies remain.” The delayed hearings were originally scheduled for mid-March, but were postponed over the government’s repeated failure to answer questions and provide documents to Yoorrook by agreed deadlines. Commissioner Burke said earlier this month that the state’s tardiness “demonstrates a fundamental misunderstanding of the truth-telling process. It is more business as usual.”

In a letter appended to a government submission to the Commission, Victorian Premier Daniel Andrews acknowledged that the ongoing overrepresentation of First Peoples in the criminal justice and child protections system is “a source of great shame” for the government, accepting that discrimination and mistreatment in these systems “are not confined to history — they persist to this day.” Andrews accepted that “significant structural change” is required to “achieve self-determination and justice,” hailing his government’s commitment to negotiate a treaty with Victoria’s First Peoples.

The substantive element of the government’s submission, focused on the child protection system, continued in a similar vein. The government acknowledged the impact of colonisation on the overrepresentation of Aboriginal children in child protection and recognised “the critical role of self-determination” in seeking to remedy the system and its outcomes.

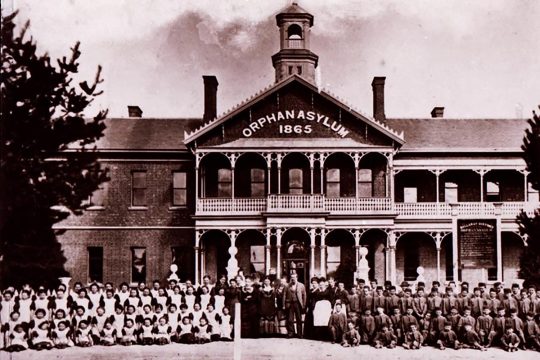

“The State’s dispossession of First Peoples, the forced removal of their children, and denial of Law, Lore and culture, created the conditions for the intergenerational trauma and social and economic inequality experienced today,” the submission said.

Alarming statistics

The submission presented alarming statistics that 1 in 10 Victorian Aboriginal children were in care as at June 2022, and were 22 times more likely to be in care than non-Aboriginal children. The government partly attributed this inequality to “structurally biased system and decision-making” which play a role in “increasing the likelihood that risk is substantiated and protective intervention, including taking a child into care, will proceed.”

Notably, the government also accepted that “the current service system is not well adapted to meet the needs of First Peoples nor to provide access to culturally appropriate services that help prevent or address risk factors.” Legislation, policies and procedures which drive interventionist approaches, and the impact of conscious and unconscious bias by reporters and decision-makers in the child protection system were partly blamed for these failures.

While the government lauded the success of programs transferring child protection decision-making powers to Aboriginal Community Controlled Organisations (ACCOs), it remains unavoidable that the rates of Aboriginal children in care have risen markedly in recent years. The rate of Aboriginal children having some interaction with the child protection system increased from 14.6% at the end of 2016 to 20.9% in 2022, and the rate of children in out of home care rose from 7.4% to 10.4% in the same period.

Racism in child protection services

It was against this background that Argiri Alisandratos, Acting Associate Secretary of the Department of Families, Fairness and Housing (DFFH), the public service body responsible for child protection, appeared before the Yorrook Commission on April 27 and 28.

Alisandratos acknowledged that the DFFH had “so far failed to reduce the rates of overrepresentation,” but pointed to a “promising” recent 3% fall in the rate of Aboriginal children in out of home care as a sign that the Department was making progress. Commissioner Travis Lovett responded: “We’ve got to be more aspirational than that…seriously.”

Under questioning from Commissioners, the public servant accepted that bias and racism existed amongst child protection workers and the system at large, and could influence judgements of harm: “That is one significant driver, and racism exists right across the broader system because children’s pathway into child protection is a product of judgements that have been made by community members and other professionals.” To this end, Alisandratos was unable to say whether the department was a safe environment for child protection staff to report racism from colleagues.

Weak cultural safety plans and funding concerns

It emerged that the Department had substantially failed to meet its target of providing 100% of children in the system with a cultural safety plan to ensure that they maintain connections to cultural values, beliefs and identity. Commissioner Kevin Bell said that “a system which produces shameful rates of child removal of indigenous people from their family is a shameful system, and it's shameful in this respect.”

Where cultural support plans do exist for children in permanent care – not a common mode of care for Aboriginal children – there is no review of their implementation and any potential for enforcement is left to birth parents bringing a court application, the Commission heard. “The department ceases its responsibilities through the issuing of a permanent care order,” Alisandros said. Commissioner Sue-Anne Hunter bemoaned the situation: “These children will then be lost to culture, country, family, mob if no one has oversight of making sure these orders [are enforced]. We are relying on goodwill and probably [the carer’s] money spent on making sure these kids keep connected.” Further, there exists no specific program set up to support non-Aboriginal permanent carers of Aboriginal children, the Commission was told.

The Commissioners emphasised the disconnect between moves to transfer greater responsibilities to ACCOs and kinship carers, and the concomitant levels of funding required. Commissioner Maggie Walter expressed concern that “responsibility for failure will be handed over to Aboriginal people while the system won’t change.”

Fiona Mcleod SC, counsel assisting Yoorrook, questioned Alisandros on gaps in the kinship carer system – where children are placed with members of extended family or existing social circles – with the public servant admitting that, in 98% of cases, “it’s longer than six weeks before anybody confirms what the kinship carer needs to provide: a safe, secure and nurturing home.” Not provisioned with timely and adequate assistance, kinship carers have in some instances been unable to transport children in their care to school and essential appointments, further continuing a cycle of inequality.

An apology

Often supporting children in addition to their own families, or dealing with old age and the “burden of intergenerational trauma and other compromised social determinants,” kinship carers are further disadvantaged by inequalities in the welfare system. The Commission heard that 96% of kinship carers received the “lowest level of care allowance”, compared to 32% of foster carers. Alisandros assured the commissioners that DFFH will be “looking at” methods of “getting more suitable support to kinship carers.”

After the Commission traversed further issues of crossover between the child protection and criminal justice systems, and cultural safety training for child protection workers, Alisandros ended with an apology:

“I accept the significant level of shame that we have openly acknowledged in terms of our delivery of support to First Peoples across the state. I accept that we have not provided adequate support and we have failed many, many children and young people.”

Further government witnesses from the child protection system will appear in front of the Commission next week, before hearings progress onto criminal justice issues over the coming fortnight. Evidence heard at these and prior hearings will inform a critical issues report in August, outlining the Commission’s findings and recommendations for reform in the child protection and criminal justice systems.