On the morning of May 17, Venant Rutunga's defence is in the spotlight with new ammunition: a video taken in 2019 during the 25th commemoration of the genocide. It was taken at the Institut des sciences agronomiques du Rwanda (ISAR) in Rubona, southern Rwanda, where Rutunga was regional director of the research centre and where he is accused of having participated in the genocide of Tutsis between April and July 1994. In the courtroom of the High Court for International Crimes in Nyanza, southern Rwanda, the sparse audience whisper to each other: "How can a video commemorating the genocide exonerate an alleged genocidaire?”

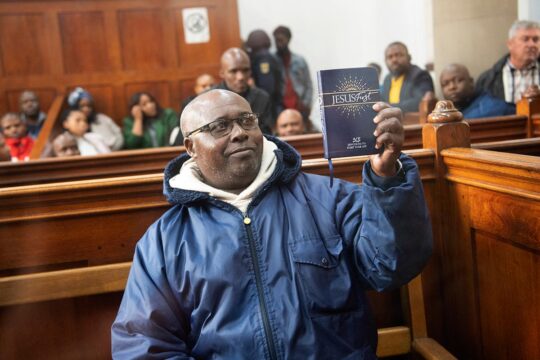

"During the genocide in 1994 against Tutsis, I was ill and I was taken to the house of Venant Rutunga, who provided a vehicle and driver to take me to hospital," says a genocide survivor in this video, recounting her ordeal at ISAR, where she had taken refuge. All she knows of Venant Rutunga is his humanitarian act. Behind his thick glasses, his face relaxes in court and a slight smile appears. It was Rutunga himself who brought before the judge this proof of his "innocence and humanity".

"A man of integrity, as good as a priest"

Shortly before the video was shown, a witness protected under the codename RV005 answered a question from the defence about the accused's conduct. "For us, he was a man of integrity, good and wise as a priest,” the witness said. “We were rather surprised to hear that he was being prosecuted for genocide against Tutsis. In short, I don't blame him for anything."

Was Rutunga a member of a political party? "Dr Rutunga must have been a member of the MRND [party in power from 1975 to 1994, accused of presiding over the genocide and since banned], because it was the party of ISAR's Director General, Charles Ndereyehe, who was his friend," the witness said. RV005, who was called by both the defence and prosecution, told the court that "as the person in charge, Rutunga took the decision to go and get the gendarmes to ensure the security of the establishment. However, they did not do what he had called them to do.”

According to the prosecution, based on the testimony of survivors, Rutunga played a key role in the massacre of over a thousand Tutsis who had sought refuge at ISAR. Instead of offering them protection, he called in the gendarmes, soldiers and militiamen to massacre them. No, "it was rather to protect them, but they did the opposite," protested the defence and the accused.

Another witness, sentenced to life imprisonment for genocide, also said Rutunga was blameless. "He was never in trouble with anyone, and I have nothing against Rutunga regarding execution of genocide at ISAR Rubona," he told the court. According to the convict, Rutunga was no longer even there at the time of the events. "This old man is here to testify with regard to the accusation that I was 'Satan' at ISAR,” explained Rutunga. “He is here to tell you what I was really like, even with ordinary people."

Who gathers the defence witnesses?

Rutunga was arrested in the Netherlands in 2019, after Rwanda issued an arrest warrant for him. In July 2021, he became the third genocide suspect to be extradited from that country, after Jean-Baptiste Mugimba and Jean-Claude Iyamuremye, in 2016.

To date, four cases have all been concluded without the hearing of defence witnesses: those of Jean Uwinkindi, Bernard Munyagishari and Ladislas Ntaganzwa - transferred by the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR) before its closure - and that of Léon Mugesera, extradited from Canada. The big obstacle, according to the defence, is the problem of legal aid to recruit defence investigators. As early as December 2012, an ICTR report on the Uwinkindi case confirmed that existing legal aid could cover "neither travel nor expenses to enable the defence to identify potential witnesses, make contact with them, take their preliminary statements and ascertain their availability to testify before the court". In February 2013, the same ICTR observer, Constant Hometowu, pointed out that, faced with this problem, the court had decided "the defence should file the list of its witnesses so that the prosecutor can conduct investigations on behalf of the accused".

In the Rwandan judicial system, different from that of the ICTR, the public prosecutor investigates on behalf of both the prosecution and the defence. Yet, notes the report, the accused has no confidence in a system where defence witnesses are contacted by the prosecutor. He fears that the prosecutor will intimidate them or force them to testify for the prosecution. "They've already tried me," Uwinkindi lamented, "and they want to give a verdict based solely on the evidence of the prosecution witnesses." As his concerns were not taken into account, Uwinkindi stopped participating in his trial.

By the close of the Mugesera trial at first instance on October 14, 2015, there had been no hearing of defence witnesses and no closing arguments from the defence. Mugesera's list of defence witnesses, which included former UN officials such as Koffi Annan, Boutros Boutros Ghali and Jacques Roger Booh-Booh as well as some ICTR detainees, appeared "unrealistic and fanciful" to the prosecution and the court. His lawyer, Jean Félix Rudakemwa, denounced the "bad faith of the judges", but the tug-of-war failed to work in the accused's favour.

Exculpatory evidence in the prosecution files

The organization of Rutunga's defence stands in stark contrast to these other cases.

According to sources at Mpanga prison, where suspects "transferred" from abroad are incarcerated, Rutunga is "very discreet" and doesn’t talk much, even with fellow inmates and former acquaintances. But his defence lawyers Sophonie Sebaziga and Néhémie Ntazika managed to find "evidence in favour of the accused" in the prosecution's case file. Sebaziga speaks of seven defence witnesses and one other potential witness. Among the witnesses living outside Rwanda, the defence mentions only "a single witness recommended by the accused but without a precise physical address". Unfortunately, "this witness dithered about where to meet, as if afraid of being kidnapped or arrested".

According to the lawyer, the difficulty of recruiting witnesses from outside the country is linked to their reluctance and fear, whereas they could "testify from abroad by videoconference". The Rwandan prosecutor's office also stresses that "witnesses arriving from abroad to testify in cases referred to national courts are not searched or seized, and are not apprehended or arrested".

A lawyer at the Kigali bar involved in at least three "transferred" cases (one of which is still ongoing) gives a harsh and different diagnosis. "The accused are torpedoing their own defence," he says, "because when they come, it's as if they're not prepared to plead their case. At heart, they already recognize that they have committed the crimes of which they are accused, and they are aware of the difficulty of finding defence witnesses, because in fact they don't have any." The lawyer, who insists on anonymity to avoid alienating clients and colleagues, says this is obvious when you ask them the question and discuss it with them. The pretext, according to him, is that the State is putting up obstacles related to witness security and lack of means to recruit defence witnesses, "but that's not the problem!”

The lawyer explains that in one of these cases, he received funds to go and investigate, and the accused himself gave him the list of people to question in his defence, at his home village. "When I saw them, they said to me why does he continue to create difficulties? Does he really think he's going to get away with it? With everything he's done?" When the lawyer brought him the results of this research, the accused "stopped trying, and we continued to brandish the slogan that we had been denied our rights".

Fear of reprisals?

Fear and silence nevertheless seem to have surrounded all the trials of transferred or extradited suspects since 2012. For Jean-Claude Shoshi Bizimana, who defended Uwinkindi and Munyagishari, this silence sometimes hides information that could lead the judge to acquit on some of the charges. Unfortunately, he laments, "even if there were witnesses, there's a kind of unfounded phobia and fear that says if I dare to testify for so-and-so, how will I be able to come back and live in the community?" This is even though he says he doesn't know anyone who has testified and suffered reprisals.

Hugo Moudiki Jombwe agrees. For this Cameroonian jurist, head of mission for the Belgian NGO RCN Justice & Démocratie in Rwanda, "to the best of my knowledge, I haven't heard of any witness who has suffered reprisals as a result of testifying. This shows that people can testify freely. We sometimes see the same defence witnesses come back in several trials. This means that they have not suffered persecution or particular pressures, otherwise they would find it difficult to come back and testify."

In the current Rutunga trial, silence is apparently not the order of the day. According to lawyer Sebaziga, "Rutunga has gradually come to understand that there are people who speak well of him, and we are approaching them to defend him. We're confident they'll testify, provided the court is neutral, of course. We'd be happy to have others, but that's enough for us.”