"And I said to the Minister: I'm glad that Switzerland never participated in either slavery or colonization.”

Four years after this statement by former Swiss minister Doris Leuthard during a visit to Benin, eight Swiss museums joined the Benin Switzerland Initiative. This initiative is part of a process of decolonizing museums. Through this initiative, Swiss museums have discovered that, of the 97 objects in the collection originating from the Kingdom of Benin, 40% come from the colonial period.

If you were to ask the Swiss what they think of their colonial history, most would say that it doesn't exist. Researchers have nevertheless proved the colonial involvement of Switzerland, or rather of certain Swiss people. For example, the triangular trade was also supported by investments from Swiss banks, and 40% of the "slave trade" was covered by Swiss insurance. The family of Credit Suisse founder Alfred Escher owned slave coffee plantations in Cuba.

What is the relationship between this colonial past and museums? Since the 19th century, "scholars" have used museums to disseminate their ideas through exhibitions. In the 19th and early 20th centuries, objects belonging to indigenous communities and collections of human remains became exhibition items. Neither intellectuals nor museum directors had the slightest regard for the religious or sacred nature of these objects. The rise of racist theories was shaping the academic thinking of the elite and, inevitably, of Swiss ethnological museums.

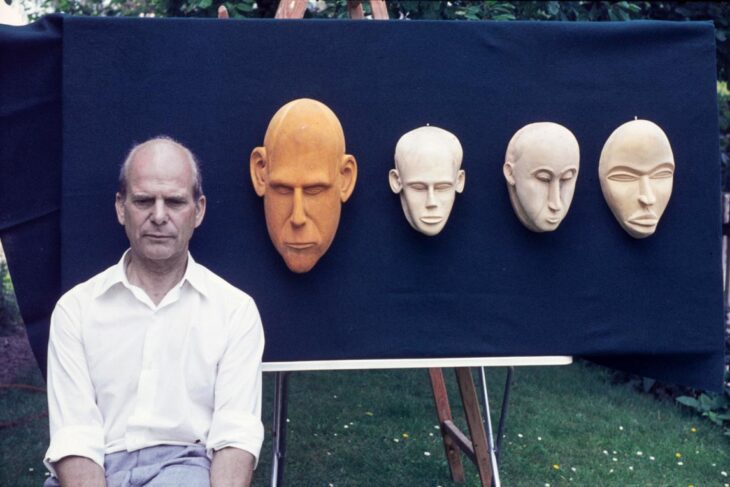

With the restitution movement, the understanding of these objects and their history has changed. This process is sometimes conceived in harmony with the cultures concerned. A case in point is a sacred mask of Haudenosaunee origin, which until recently was housed at the Musée Ethnographique de Genève (MEG). It was only on February 7, 2023 that the MEG returned it. The ceremony that followed demonstrated the change in attitude: as a sign of respect for its sacredness, the mask was locked in a box during the event, and the ritual welcoming its return was not filmed.

What is decolonization?

There is no agreed definition of what decolonization means. According to the Swiss Association for Provenance Research, decolonizing implies the act of denouncing the colonial ideology that persists in our societies. For writer Elisa Schoenberger, decolonizing means opposing the white domination that continues to silently structure our societies and the violence, latent or not, in relations between Western and non-Western communities around the world. The consensus is that these unequal power relations manifest themselves in culture, language and social and economic relations. They persist throughout our society, and museums are no exception.

The ethnographic museum was born with the first plundering campaigns on the American continent in the 16th century. Towards the end of the 18th and beginning of the 19th centuries, the museum became one of the instruments of European imperial policy. Through images and objects, they helped to disseminate, affirm and establish the West's claim to superiority over the "savage". Museums embody the authority of knowledge and convey a certain narrative of national history: a glorifying, heroic epic. This is also the case in Switzerland, where silence about the colonial past remains shrouded in a thick veil.

Swiss museums decolonize

Over the past 20 years, curators at Swiss museums have become increasingly aware of this opacity. In March 2002, the Musée ethnographique in Neuchâtel opened the exhibition "Musée cannibale". This pioneering move paved the way for the decolonization of Swiss museums. In 2010, the Rietberg Museum in Zürich launched a cooperation and restoration project with Cameroon linked to its extensive collection from the Kingdom of Bamoun. In 2019, the Musée ethnographique de Genève included in its strategic plans the need to "make visible the violent and unequal history of colonial and neo-colonial collections".

The Black Lives Matter movement has accelerated this process. According to Professor of History and International Politics Davide Rodogno, several Swiss museum directors have realized that acknowledging the violence suffered by colonized peoples and the stereotyped, demeaning representations of non-European peoples in museums is a crucial step towards dismantling unequal relations.

The Swiss National Museum's 2024 exhibition will be devoted to Switzerland's colonial past. Its director, Denise Tonella, points out that the existence of a Swiss colonial history still surprises most Swiss people. For this reason, she recommends starting by acknowledging the existence of this past and telling its story.

Swiss identity at the heart of the debate

Certain stances against museum moves to decolonize illustrate the controversies around this issue. These efforts on the part of museum directors contrast with certain reactions from the Swiss public. Some people reject, deny or openly oppose the idea of a colonial Switzerland and these initiatives.

"Switzerland has a problem with its image; it likes to see itself as neutral, democratic, humanitarian and therefore irreproachable, always on the side of good,” says Helen Bieri Thomson, director of the Château de Prangins. “It's difficult to deal with the less glorious themes of the past and the amnesia that concerns Switzerland."

The process of decolonizing Swiss museums involves issues of identity, and opens the way to deeper reflections: do these various projects highlight a dangerous crisis for the Confederation? Does talking about Swiss colonial history call into question the myth of "Sonderfall", Swiss exceptionalism? If so, why and for whom should Switzerland destabilize national history (built around a narrative of neutrality and humanitarian tradition) by insisting on colonial issues that don't belong to the Swiss? And if Switzerland is decolonizing to satisfy its own needs, to what extent will the process take colonized communities into account? If the decolonization process is to be welcomed by the Swiss population, these sensitivities must be taken into account and addressed throughout the Swiss decolonization process.

Towards the end of ethnographic museums?

Thanks to the decolonization process, looted properties, objects and human remains have begun to be recognized for their value and history. This first step enables discussions to be initiated concerning the return of objects, as in the case of the MEG. Formerly colonized communities can have "their version of history" recognized.

To break these unequal dynamics, museums need to be more ambitious. Professor of History and International Politics Mohamed Mahmoud Mohamedou is categorical in this respect: the decolonization of museums requires the decolonization of the mind. Ethnographic and history museums, like other public institutions, could start by making public what they have omitted to say about the past. They should adopt a critical approach to themselves. This would involve publicizing the museum's history, its colonial implications, its funding and the provenance of its objects.

This approach raises deeper questions about the very nature of museums. Indeed, if ethnographic museums are a product of colonization, wouldn't successful decolonization imply their definitive closure? In other words if, as argued by social anthropology professor Fabien Van Geert, the representation of the Other is the raison d'être of the ethnographic museum, does its existence still make sense?

This article, translated by Justice Info, is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons licence. Read the original article.

Doctoral student in History and International Politics at the Geneva Graduate Institute, Letizia Gaja Pinoja researches Swiss colonial and post-colonial history.