This article marks the first publication of our section "Pointers". Designed to facilitate access to Justice Info, it opens a gateway to international justice, entering into the complexity in an uncomplicated way.

the roots of the rwandan conflict

The origins of Hutu and Tutsi identity

The genocide of Tutsis in Rwanda in the 1990s left a deep mark and became an important subject of work for international justice. Understanding who the Hutus and Tutsis are enables a better comprehension of the subject. "Hutu" is said to derive from the Rwandan word "untu" which means "owner of the land" or "farmer." The Hutus were mainly farmers. "Tutsi" is often interpreted as deriving from "utusi", which means "one who owns cattle." They were mainly breeders.

A third component of Rwandan society are the Twas, a Pygmy people who are a tiny minority but the oldest living in the region, mostly from hunter-gathering.

Late 1850’s: Growing tensions between the two groups

The two main groups are distinguished as such: the first is associated with farming, the second with cattle raising. However, they share the same language, beliefs and culture, and intermarriage is common. Switching from one group to another is possible. The clan lineages may also be mixed, hence some researchers do not consider these groups as ethnic groups.

However, before the colonial period that started in 1850, the Tutsis formed a ruling elite, especially around the king, the mwami. But he didn’t control the whole of the contemporary territory of Rwanda: in the northwest, Hutu leaders challenged his authority.

the belgian colonization and instrumentalization of the ethnic division

The Belgian colonizers' system of racial classification and favouritism

In the 19th century, European powers were interested in Africa's wealth and colonizing countries occupied several parts of the continent. The Berlin Conference was held from November 1884 to February 1885 in order to establish order and settle disputes between the powers. It was time for great colonial sharing.

African territories were allocated to the colonial powers on the basis of their possessions and their actual presence on the ground at that time, regardless of the ethnic, cultural or historical realities of the indigenous peoples. Ruanda-Urundi, which includes present-day Rwanda and Burundi, was attributed to the German empire.

After the defeat of Germany in World War I, Belgium obtained a mandate from the League of Nations (an international organization created for the purpose of promoting peace and cooperation among nations) to administer Ruanda-Urundi.

The use of ethnic propaganda to divide and rule

In Rwanda, Belgium established a system of governance based on ethnic division and controlled the territory directly. Belgium favoured the Tutsis, judging them closer to the Europeans because of their presumed physical appearance and their higher socio-economic status. Tutsi chiefs administered the regions and collected taxes, stirring up tensions with the Hutus.

The Belgians fixed the previously permeable ethnic identities by drawing up ethnic identification cards. The hierarchy between the groups was no longer a matter of socio-economic status, it was stiffened and based on physical criteria such as height, shape of the nose and texture of the hair. One became irreparably Tutsi or Hutu by the father.

independence and escalation of violence

1962: Rwanda's independence and rising ethnic tensions

In the late 1950s, the desire for independence from the Belgian regime intensified in Rwanda and was followed by acts of violence between Hutus and Tutsis. In 1959, a first Hutu uprising, called the "social revolution", took place. The first anti-Tutsi pogroms followed and forced thousands of them to flee to Uganda, Burundi or Congo-Kinshasa.

In 1962, Rwanda gained its independence from Belgium. The Hutus took power. Tutsis became marginalized, discriminated against, or were forced into exile.

In July 1973, Juvénal Habyarimana, a Hutu general, took power. He imposed one-party rule by the MRND (National Revolutionary Movement for Development). An ethnic quota system was established for access to education or public service employment.

Violence Before the Civil War

Several waves of massacres of Tutsis happened between 1959 and the mid-1960s, then again in 1972-1973. In December 1963, the first major massacre of Tutsis occurred in Rwanda. Since Tutsi civilians were targeted as such, the word "genocide" was even used in 1964 in the press, notably in La Tribune de Lausanne, which on 12 February 1964 carried the headline "True genocide in Rwanda." No punishments were imposed on the perpetrators of the crimes, openly supported by the Rwandan authorities.

Between civil war and hope for peace

The 1990 civil war

During the 1980s, texiled Tutsis increasingly asked for the right to return to their country of origin. Some of them decided that this right had to be won with weapons. The Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) was established in Uganda.

After 1990 and the end of the Cold War, pressure increased on the Habyarimana regime to democratize and find a solution to the refugee issue. At the same time, Habyarimana’s political party created the Interahamwe, militias composed of radicalized Hutu youth used to support the regime. They promoted ethnic propaganda, recruited members, organized military training and carried out violent attacks against Tutsis and political opponents.

In October 1990, the RPF militarily attacked Rwanda from Uganda. The Rwandan Armed Forces (FAR) initially stopped the rebel group thanks to the intervention of the French army. But the civil war began, with a new RPF breakthrough in February 1993 in the north of the country, which brought it just a few dozen kilometres from the capital Kigali and caused massive displacement of Hutu populations within the country. At that time, Rwanda had nearly one million displaced persons, representing one seventh of the population. The RPF offensive was again stopped thanks to French military support.

From the beginning of the conflict, reprisals against the Tutsi civilian population were part of Habyarimana supporters’ strategy. There were mass arrests and new massacres in certain places. Among the Hutu, fear of the RPF took root, fuelled by increasingly virulent propaganda.

At the same time, an internal democratization process was launched. A multiparty system was restored and a democratic Hutu opposition contested the MRND’s power with increasing success. Democratization and political radicalization were mutually reinforcing against a backdrop of armed threat.

Interahamwe militias

Interahamwe militias grew out the youth wing of president Habyarimana’s MRND party. They instilled fear during election campaigns at the beginning of the ‘90s and were progressively militarised and structured into a paramilitary force. From April 1994, these militias spearheaded the genocide of Tutsis.

Their role was the focus of many trials held in Rwanda and at the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR), established by the United Nations at the end of 1994. Tens of thousands of militiamen were tried by Rwandan courts.

Several prominent figures were accused of being involved in the creation, management or support of Interahamwe militias. They include former leaders of the MRND party, tried by the ICTR, and businessman Félicien Kabuga, arrested after 26 years on the run and being tried in The Hague.

the Arusha Accords and the creation of a transitional government

Some hope for peace appeared in 1992 when President Habyarimana and the RPF agreed to end the armed conflict. The negotiations lasted from June 1992 to August 1993. They took place in Arusha, Tanzania, and led to a power-sharing plan, including a gradual demilitarization and the creation of a new national army integrating RPF fighters and facilitating the return of Rwandan refugees.

Political reforms were planned with the establishment of a transitional government led by the Hutu opposition. The Arusha agreements, as they are called, also provided for more than 2,000 UN peacekeepers to be sent and for the French army to withdraw at the end of 1993.

However, the implementation of these agreements and the installation of United Nations forces were subject to several obstacles and delays.

1994: genocide begins

Failure of the peace agreements

The installation of the transitional government took time and tension continued to grow in the months following the signing of the Arusha agreements. Political parties split between supporters and opponents of the agreements. Hutu extremists gathered in the so-called "power" movement.

“Hate media" started to spread. The most famous of these is the Radio-télévision libre des mille collines (RTLM). Kabuga, a member of the presidential family and Hutu extremist, was its main financier and chairman of its board of directors. RTLM’s modern-sounding programmes fomented ethnic tension and called for the elimination of Tutsis

On its side, the RPF built up its weapons and was accused of perpetrating attacks.

The assassination of President Habyarimana: a fatal turning point

April 6, 1994 was a fatal turning point. That evening, President Habyarimana was returning to Kigali by plane, accompanied by the new Burundian President Cyprien Ntaryamira (a Hutu) and a few dignitaries from the Rwandan regime. As the plane was about to land, it was hit by two missiles, instantly killing everyone on board.

The identity of the perpetrators of the attack has never been established. Multiple theories circulate, but the two main ones point to either Hutu extremists wanting Habyarimana dead because he was too favourable to power sharing; or the RPF, on grounds it wanted to provoke resumption of the war and seize power alone.

Involvement of the civilian population in the massacres

Acts of violence were first committed on the night of April 6 to 7, 1994. On the morning of the 7th, several of the main Hutu and Tutsi leaders in favour of the Arusha peace accords were assassinated, as well as ten Belgian UN peacekeepers charged (in vain) with protecting Prime Minister Agathe Uwilingiyimana, who was executed by the presidential guard along with her husband.

Thus the genocide of the Tutsis began. They were systematically massacred at roadblocks erected throughout the country, in churches, and on the hills. For three months, the country was embroiled in unprecedented violence. The attackers were armed with machetes, hoes and studded clubs. They were supported by the gendarmes, the police and the military. The entire Hutu population was strongly encouraged to participate in the killings, including by the civil authorities who transformed the custom of umuganda -- a day of collective work -- into a duty to kill. RTLM called directly for murder, guided the killers in their hunt and indicated the Tutsis who were either still alive or hidden. Hutu human rights activists and opponents were systematically targeted by the militiamen.

RPF troops also committed crimes against humanity.

The number of victims of the genocide remains controversial. The estimated number ranges from 600,000 to over a million dead. A considerable part of the Rwandan Tutsi population was exterminated in circumstances of extreme cruelty, while hundreds of thousands of women are raped.

Machetes and Kabuga

In the months leading up to the 1994 genocide, a massive importation of machetes took place in Rwanda, which became the subject of several judicial investigations. These investigations led to Félicien Kabuga, suspected to be one of the planners of the genocide. Many prosecutors agree that the import and distribution of agricultural tools was preparation for the killings, but the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR) ultimately struggled with the lack of tangible evidence establishing a direct link between these imports and the preparation of the crime.

MORE INFO - Why Kabuga is no longer accused of importing machetes for genocide

Kabuga is thus accused of genocide, complicity in genocide, direct and public incitement to commit genocide, conspiracy to commit genocide, persecution and extermination as crimes against humanity. However, he is not being tried for the import of those thousands of machetes. He was arrested in France in May 2020 after 26 years on the run. He is being tried before a UN jurisdiction, the "Mechanism", which took over from the ICTR.

Recently, Kabuga was deemed unfit to continue his trial for health reasons. Now, three options are before the appeal chamber: to terminate the proceedings, merely suspend them, or us an unprecedented alternative procedure.

MORE INFO - Kabuga: Heading for a palliative trial?

The international community’s inaction

Faced with the third officially recognized genocide of the 20th century, the lack of reaction from the international community has sparked unprecedented debate. The United Nations had to make its mea culpa on the serious shortcomings of the Mission for Assistance to Rwanda (UNAMIR), and its massive withdrawal in the first weeks of the massacre. The African Union also had to set up a commission of inquiry. And three other countries have been particularly blamed for their responsibility:

- Belgium, already implicated for having set the scene of ethnic hatred during the colonial era, had the best trained and equipped contingent of UNAMIR. It withdrew unilaterally from Rwanda after the massacre of ten of its peacekeepers on April 7, 1994. A parliamentary commission of inquiry described Belgian political responsibilities there.

- France, the main political and military support of the Habyarimana regime, has been accused of "complicity" in the genocide. It was the only power to have succeeded, at the end of June 1994, in an armed intervention to definitively protect the Tutsis still alive – the famous Operation Turquoise but was accused of having slowed down the progress of the RPF, of having abandoned Tutsis in danger in western Rwanda and of not having arrested certain leaders in the area it took over. Two official commissions of inquiry were set up in France after the genocide.

- The United States is accused of refusing to call the massacres genocide while they were in progress, so as not to have an obligation to intervene as the Convention on the Prevention of Genocide requires. President Bill Clinton apologized on Rwandan soil.

Definition of Genocide

Genocide is an international crime legally defined as the intention to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnic, racial, or religious group by committing acts such as murder, serious bodily or mental harm to the members of the group, imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group, or forcibly transferring children of the group to another group.

MORE INFO - All our articles on genocides, in Rwanda and elsewhere.

The post-genocide era and justice initiatives

RPF takeover and the refugee crisis

On July 4, 1994, the RPF (Rwandan Patriotic Front) took control of Kigali, and by mid-July, they had gained control of most of the country, marking the end of the genocide. To avoid potential reprisals, around 1.7 million Hutus fled Rwanda and sought refuge in camps located in Burundi, Tanzania, and Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of Congo). This massive exodus led to an unprecedented humanitarian crisis and prompted a significant international intervention.

Mass justice for mass crimes

After the genocide, a government of national unity was initially established. General Paul Kagame, the military leader of the RPF, became the dominant figure in the country and the Minister of Defence. One year later, the ruling coalition, which included several prominent surviving Hutu democrats, came to an end, and the RPF effectively took sole control of the country. In 2000, Kagame became president and remains in office to this day.

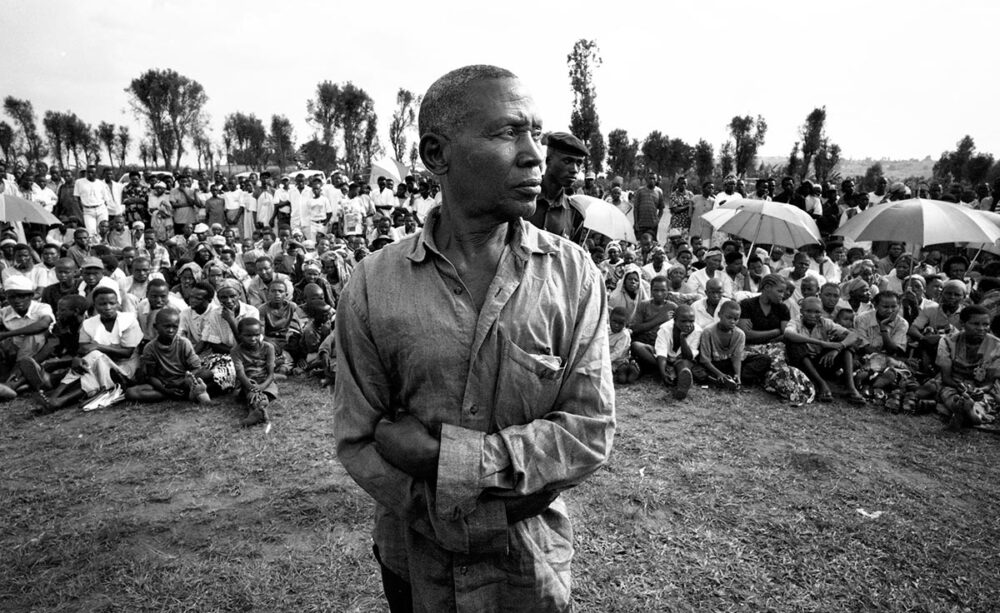

Justice played a central role in Rwanda's post-genocide government policy. As early as 1996, national courts began conducting trials, resulting in the prosecution of approximately 9,000 individuals. Later, the "gacaca" courts were established, representing a unique experiment in mass justice after a mass crime. These courts aimed to hold everyone accountable for their actions, from major criminals to minor war profiteers, while also facilitating national reconciliation. Additionally, a reparations fund for the victims of the genocide was set up.

There was no truth commission in Rwanda, and crimes committed by the RPF were never judged by the special courts established in the country. However, efforts to preserve the memory of the genocide have proliferated throughout the country, with multiple museums and memorials.

Although the end of the "gacaca" courts largely marked the resolution of the genocide-related litigation in Rwanda, some ongoing or upcoming criminal trials target suspects of the genocide arrested abroad and sent back to Rwanda.

Local and international justice

In the history of justice, never before has a mass crime been as extensively prosecuted as the genocide of the Tutsis in Rwanda. The Rwandan government established over 12,000 courts to ensure that no one would escape accountability for their actions. More than a million individuals were brought to trial. Additionally, the United Nations set up a special international tribunal for Rwanda, and several countries also prosecuted suspects arrested on their own soil.

MORE INFO - Our interactive feature Rwanda: the most judged genocide in history.

National and gacaca tribunals

At the national level, alongside the national courts, Rwanda implemented a process heavily inspired by traditional "gacaca" courts (community village courts held in the open air) to prosecute those responsible for homicides, violence, serious violations against victims, and property-related offenses.

The UN international tribunal

The United Nations created the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR) on November 8, 1994, to try individuals accused of genocide, crimes against humanity and war crimes. This UN tribunal pursued individuals regardless of their status, whether political, military, or civilian. Its primary mission was to prosecute high-ranking officials who had sought exile and were beyond the reach of Rwandan justice.

The ICTR conducted 75 trials, targeting the highest-ranking officials of the former Rwandan army, numerous members of the interim government that governed the country between April and July 1994, leaders of the ruling party MRND, several prefects, other local authorities, clergy members, journalists, businessmen, and a few militia leaders.

The first person convicted of genocide was Jean-Paul Akayesu, a former mayor, sentenced to life imprisonment for the massacre of 2,000 Tutsis in his municipality. The second was Jean Kambanda, the former Prime Minister, who received a life sentence after pleading guilty. The trial of media figures took place, involving two leaders of RTLM (Radio Télévision Libre des Mille Collines). However, the most symbolic and decisive judgment on the substance was probably that of Colonel Théoneste Bagosora, former Chief of Staff in the Ministry of Defence, considered the "principal default suspect" of the genocide. One woman, former Minister of Family Affairs Pauline Nyiramasuhuko, was convicted of genocide. And a foreign national, Italo-Belgian Georges Ruggiu, a former presenter at RTLM, received a twelve-year prison sentence after pleading guilty.

The ICTR officially completed its work in 2015 and was replaced by the Mechanism for International Criminal Tribunals (MICT), which handles archives, detention, prison releases and witness protection, among other matters. The ongoing trial of Félicien Kabuga is currently before this jurisdiction.

Universal jurisdiction trials

In cases where a country prosecutes crimes committed on another territory due to their exceptional gravity, it is known as the principle of "universal jurisdiction."

According to Charity Wibabara, who heads the unit responsible for prosecuting genocide fugitives within the Rwandan general prosecutor's office, "25 prosecutions have been initiated by foreign countries for the genocide of the Tutsis. Notably, six people were tried in France and nine in Belgium. Other judgments were rendered in the Netherlands, Norway, Finland, Germany, Denmark, Switzerland, and Canada.”

MORE INFO - In this article, the complete list of Rwandans on the run, transferred, or tried abroad: Rwanda: slowly, the net of justice is closing on the last genocide fugitives.

MORE INFO - Our article on the Hategekimana trial, tried for genocide and crimes against humanity. This is the fifth Rwandan universal jurisdiction trial to open in France: Genocide in Rwanda: the multiple lives of a gendarmerie officer on trial in Paris.