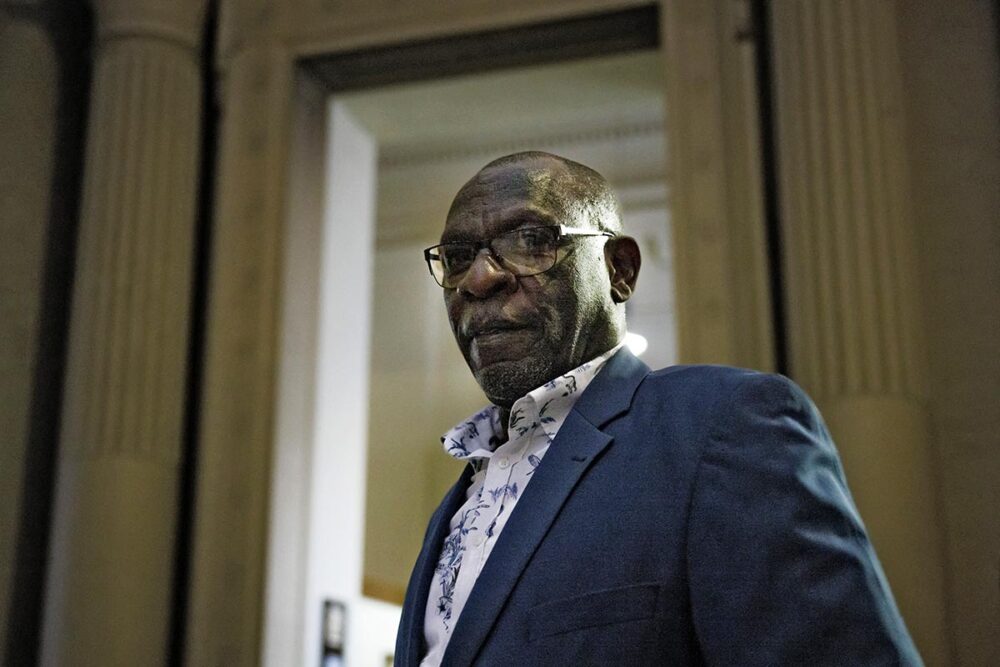

Séraphin Twahirwa, a tall man in a suit with impeccable white shirt, stood right before the president of the Brussels Assize Court. He was appearing a free man and, microphone in his right hand, he began to answer general questions. When was he born? Who were his parents, brothers and sisters? Where did he live? What education and training did he receive? Judge Isabelle De Saedeleer followed a traditional line of questioning: first the life story, then the facts. The accused began his account of his childhood in French, with an interpreter standing to his left, ready to translate any words that might be spoken in Kinyarwanda.

Twahirwa was born in the Bushiru region of northern Rwanda in 1957. He was the eldest of six children born to his father, a member of the national police force, and the first of his three wives. The accused dropped out of school in fifth grade because his mother could no longer afford to pay the fees. With some emotion he confessed that he had been obliged to beg at that time. Around the age of 13 or 14, he left for the capital, Kigali, where his father now lived with his second wife. He attended a carpentry school, learned to play basketball and was then hired as a driver by the Ministry of Public Works, Water and Energy - Minitrape, as it is known in Rwanda. But on his first day at work, he was involved in a serious road accident. Seriously injured, he was taken to Belgium, where his left leg was amputated below the knee. Returning to Rwanda a few months later, he rejoined the Minitrape, this time as a warehouse assistant.

No link with the Interahamwe...

On the eve of the genocide, Twahirwa was a married man with three children, living in a house in the centre of Kigali, in the Karambo cell of Gikondo sector. Rwanda is divided into strict administrative units.

When the court president turned to the years leading up to the genocide, between 1990 and 1993, the exchange became less clear-cut. Twahirwa admits to having been a supporter of the Mouvement révolutionnaire national pour le développement (MRND), the party of Rwandan President Juvénal Habyarimana, but he denies having been a member of the MRND's youth movement, the Interahamwe, which was gradually transformed during those years into a veritable civilian militia, armed and trained in combat. Prosecution witnesses say that Twahirwa was one of those responsible for punitive expeditions carried out by the Interahamwe against Tutsis in Gikondo in 1990. Other eyewitness accounts suggest that around a hundred militiamen were under his command from 1992 onwards.

"I can tell you, Madam President, that I was not active among these Interahamwe," he replied, adding that it would not have been possible because of his physical handicap. As for his nickname of "President", which emerges from certain testimonies, it is not related to his presumed status as an Interahamwe leader, but to the fact that he was once the most gifted basketball player in his neighbourhood, he asserted.

... nor with the Habyarimana family

When questioned about his alleged family ties with Agathe Kanziga, the influential wife of Habyarimana (President of Rwanda between 1973 and 1994), Twahirwa denied this. According to witnesses, Twahirwa's father and Kanziga's father were brought up under the same roof, and were therefore brothers or cousins. According to others, Twahirwa boasted of his kinship with the presidential family and appeared to be protected, particularly when he was released in June 1993, just after being arrested on suspicion of murder.

Twahirwa told the court that this alleged relationship was simply a mix-up between his father and one of the former First Lady's brothers, since they had the same first name and lived two kilometres apart. As for his swift release in 1993, he had no explanation. "First of all, I was handcuffed and taken to the central police station. The public prosecutor's office came. I went to court and my lawyer pleaded my case," was all he said.

On the evening of April 6, 1994, President Habyarimana's plane was shot down just before landing in Kigali, killing all its passengers. The attack, for which responsibility has never been established, was the event that triggered the assassinations of Hutu opponents and the genocide of the Tutsis, which began on the morning of April 7 in the capital and then spread throughout the country for three months. However, Twahirwa denied the existence of roadblocks in his Karambo neighbourhood from that date onwards. These roadblocks were manned by civilians and the Interahamwe, who checked people's identities and immediately killed those who had the word "Tutsi" on their identity card or simply looked like one. According to the prosecution, it was Twahirwa who supervised these roadblocks, particularly one at the place known as "cabine d'eau". "There was no roadblock at that place, there wasn’t the space," retorted the accused.

"If things turn bad, what can I do?”

He claims he lived in hiding with his family between 6 and 11 April 1994, then fled northwards to his native region. "I was from there and I thought if things turn bad, what can I do? I said to myself that I have to evacuate my wife [of Tutsi ethnicity]. I had heard the military say that the Tutsis were wanted because they were considered responsible for the attack," he told the court.

According to Twahirwa, after that he never left northern Rwanda before fleeing to neighbouring Congo with his wife and their children on July 17, like hundreds of thousands of Rwandan Hutus did after the victory of the Rwandan Patriotic Front Tutsi rebellion. During most of this period, i.e. from April 6 to June 30, Twahirwa is accused of having been in Kigali where he killed or ordered the killing of at least 56 people, attempted to kill or cause the deaths of at least 13 others, and raped 12 women. But the accused's position is clear: he denies everything. This heralds a trial of directly opposing positions, with two totally irreconcilable versions of events.

Pierre Basabosé, the big absentee

This sixth trial in Belgium of alleged Rwandan genocidaires is due to continue with the hearing of nearly a hundred witnesses, before a verdict expected in early December.

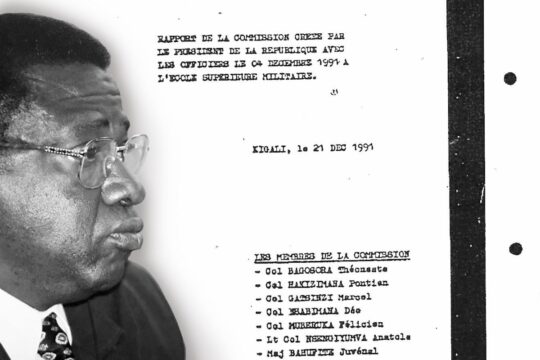

A second man is accused in this case, Pierre Basabosé, but he is not appearing. Ailing with senile dementia, Basabosé was hospitalised three days before the start of the trial for at least two weeks, due to a bacterial infection. The 76-year-old former soldier and businessman, who is accused of having given money and weapons to the Interahamwe leaders of Gikondo, in particular to Twahirwa, seems highly unlikely to take part in the proceedings. His lawyer, Jean Flamme, is nevertheless representing him at the hearings.