When Gustavo Petro came to power in Colombia a year and a half ago as the first left-wing president in its history, he sought to distance himself from his right-wing predecessor Iván Duque on multiple fronts. One of the clearest was to pledge implementing the peace agreement signed by the government with the former Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) guerrillas in 2016, whose historical significance Duque strove to dilute and even tried to torpedo.

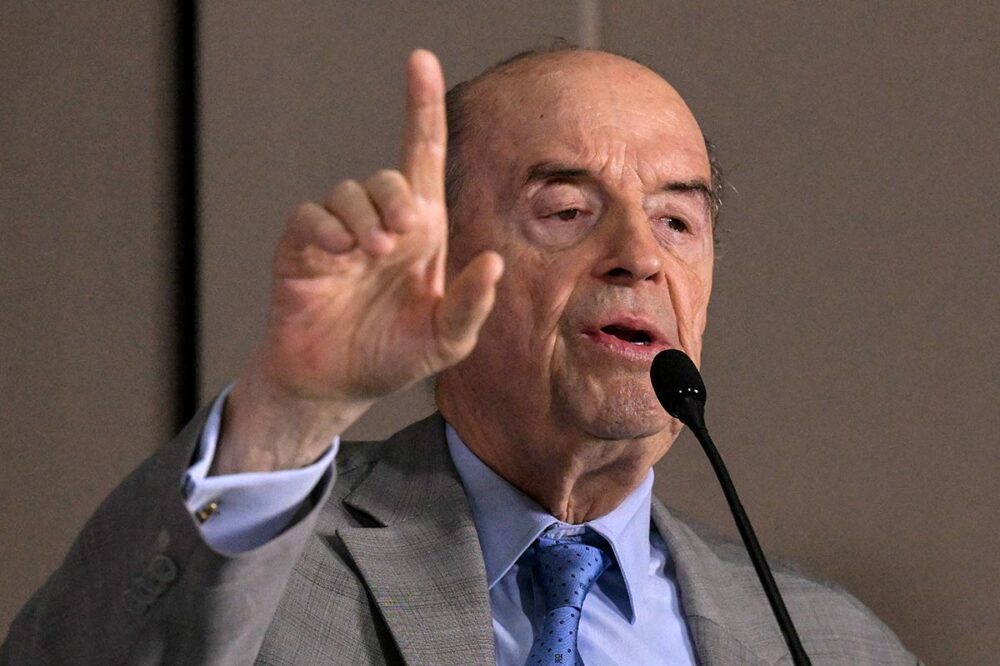

However, one of the highest-ranking officials within Petro’s government, Foreign Minister Álvaro Leyva, has been throwing darts at the Special Jurisdiction for Peace (JEP), the judicial arm of the transitional justice born out of the peace agreement, for most of 2023. “We’re concerned that the model institution for the whole world, the one designed to bring justice after decades of horrible internal conflict, is going off the rails from what it was shaped out to be with enormous effort”, Leyva told the UN Security Council on October 11th, during the presentation of the UN’s quarterly report on its verification mission in Colombia.

“Time has come to review and correct the JEP”

As a preamble to his critique, Leyva explained that he’d been one of the architects of the transitional justice chapter. “I admire the JEP as if it were a person, not an institution, and I love it,” said the man who was one of the FARC's advisors at the negotiating table for four years. “The time has come to review its actions in order to correct them,” he warned sternly, suggesting risks to peace in the country and full truth for the victims. Days later, President Petro sent a communication to the UN taking up some of his Foreign Minister's points.

The JEP responded with a communiqué asking respect for its independence and stressing that the government and the former FARC “are not allowed to issue orders and orientations regarding decisions” of the transitional justice institutions. “The fact that it was created by virtue of the final peace deal doesn’t confer the signatory parties any guardianship over its management,” it said.

But two weeks later, Leyva resumed his attack with a tweet suggesting that the JEP, "contrary to its design", "curtails truth" and "shatters peace".

"The JEP’s progress is cause for optimism"

Leyva's position contrasts with the UN’s report on the progress of the transitional justice. In the three-month period it covered, between July and September, the special tribunal indicted 10 former FARC regional commanders for kidnapping, nine former military officers for extrajudicial executions (including General Mario Montoya, a former Army top commander) and 14 former FARC rebels for crimes committed against indigenous and Afro-descendant communities in the Nariño regional case. They were all charged with war crimes and crimes against humanity. In addition, the JEP held two hearings where indictees publicly owned up to their crimes and apologised to their victims.

Despite delays in several macro-cases, by the end of 2023 the JEP will have indicted 156 persons, including 50 former FARC members and 102 former military officials. 80 of them have chosen to acknowledge their responsibility and have therefore chosen the transitional justice track in which they may receive - in exchange for providing truth and redress to their victims - a more lenient 5-to-8-year sentences in a non-prison setting. In other words, 90 percent of the accused have chosen to admit to their crimes.

"This progress," argues the report signed by UN Secretary General Antonio Guterres to which Leyva was responding, "is cause for optimism and I am confident that the Special Jurisdiction [for Peace] will continue to carry out its crucial task of fulfilling rights to truth, justice, reparation and non-repetition”.

The alleged exclusion of paramilitaries

"Unfortunately, the JEP ex officio has limited the appearance of those who have the right to this special justice", Foreign Minister Leyva said in his speech to the UN. He was referring to the 35,000 former right-wing paramilitaries, who demobilised between 2003 and 2006. At the time, they had their own transitional mechanism dubbed “Justice and Peace”, which allowed them to share previously ignored truths and to receive reduced 5-to-8-year prison sentences for thousands of atrocities. For that very reason, the peace agreement with the FARC, a decade later, excluded them.

According to Leyva, many of these paramilitaries are now willing to tell the transitional justice new truths and should be accepted under the principle of favourability, which stipulates that a person is entitled to the most beneficial criminal treatment available. The JEP, he argued, "has permanently disregarded" this right and has "cast aside norms that should be rigorously applied", thereby "conditioning truth-telling, closing off or preventing it from fully reaching the JEP and the knowledge of the victims and public opinion".

It wasn’t the first time that Leyva had presented this criticism. In July, during the publication of the previous UN report, the Foreign Minister had warned the Security Council that it was necessary to "remove obstacles that hinder the access of paramilitaries to the JEP without any justification whatsoever".

“It’s necessary to listen to total truth”

As proof of the supposed good will of the paramilitaries, the Foreign Ministry has organised two events - which it termed 'truth meetings for non-repetition' - and plans to hold more.

First, in May, at the Juan Frío crematorium ovens near Cucuta and the Venezuelan border, Salvatore Mancuso confessed - via video link from his prison cell in the US - that they buried hundreds of victims of forced disappearance in mass graves in Venezuelan territory. Leyva then signed an agreement with Nicolás Maduro’s government to search for them. And in August, Carlos Mario Jiménez - better known by his nom de guerre 'Macaque' - recounted how, two decades ago, they hatched a plan to assassinate the current Foreign Minister and President Petro. Leyva underscored that it’s necessary to listen to them in order to know "the total truth" and even proposed reviving the Truth and Reconciliation Commission that closed its doors last year, to listen to the paramilitary high command.

This "total truth", Leyva insisted, could only be completed if the JEP stops "conditioning or limiting those who want to tell it". He didn’t explain what truths they would provide that they hadn’t revealed when it was their obligation nor how to trust those who, like Macaque, were expelled from Justice and Peace for failing to comply with their commitments.

"As we have stated publicly, we don’t share the Foreign Minister’s judgements. We reaffirm the JEP’s autonomy and independence as a high court in a state governed by the rule of law," its president Roberto Vidal told Justice Info. After Leyva's last speech, he travelled to New York and The Hague to present the Colombian special court's position on this clash of competences to institutions such as the International Criminal Court.

A paramilitary boss lands in the JEP

Over the last four years, the JEP had indeed rejected submission requests of dozens of former paramilitaries such as Rodrigo Tovar 'Jorge 40', Salomón Feris, Andrés de Jesús Vélez, Carlos Moreno Tuberquia 'Nicolás' and even Mancuso, as civilian third parties who took part in the armed conflict. The same happened with politicians and civilians who claimed to have worked with the paramilitaries, but whom the JEP decided failed to provide the full truth, such as former congressman Jorge Visbal, former mayor Jorge Luis Alfonso 'Gatico' or land dispossessor Sor Teresa Gómez. Many had sought the JEP because Justice and Peace’s logic of individual trials and partial indictments meant years and greater legal insecurity, but also because several had been excluded for not providing the truth.

However, a month ago, the JEP accepted Salvatore Mancuso as a subject and thus a potential beneficiary of its sanctions. After the JEP’s Acknowledgment Chamber had rejected Mancuso and he appealed, another instance of the special tribunal decided to admit him not as the second-in-command of the United Self-Defence Forces of Colombia (AUC), but as a "hinge or connection point between the military and paramilitary apparatus".

In their decision, three justices of the JEP’s Legal Status Definition Chamber argued that Mancuso was a "subject materially and functionally incorporated into the security forces" and had "a determining role in the design, planning and execution of joint macro-criminality patterns" with the state security forces. That is why they decided to consider him, not as a civilian third party, but a "de facto state agent".

Interestingly, a fortnight ago Mancuso appealed the JEP’s decision to admit him. He did so because he disagreed with the special tribunal’s view that it should only assume part of his criminal investigations and that Justice and Peace should still try him for other crimes, something that would reduce the JEP's room for manoeuvre in granting him benefits and could create a risk of legal insecurity (a point on which one of the JEP's magistrates agreed in a partial dissenting opinion).

The risks of overburdening the JEP

The acceptance of Mancuso and Leyva's demands to receive more paramilitary leaders have raised concerns about the impact this could have on the work of the JEP.

To date, the JEP has not yet issued convictions in cases where perpetrators are acknowledging responsibility, nor has it detailed what its sanctions will look like. It has also yet to present indictments in three of the seven macro-cases it opened in 2018, including the child recruitment case against FARC, the case on the extermination of the Patriotic Union political party against state agents, and the Urabá regional case against both, as well as in the four it announced more recently. The sexual violence case was unveiled in September. In addition, the JEP prosecutor's office has only presented two accusations for those who don’t admit responsibility, and those adversarial trials have not yet begun.

"The JEP should concentrate on those cases (from which truths will emerge) instead of seeking truths through the opening of new processes," warned criminal lawyer Yesid Reyes, who was the Colombian Justice Minister during the negotiation of the transitional justice chapter with FARC. Opening the door to paramilitaries, he argued, increases the judicial burden and creates a risk for a JEP that "is already beginning to glimpse temporary difficulties in evacuating all the cases it has pending". It has a timetable of 10 years to present indictments and 15 years to judge them, almost half of which have elapsed.

"Total truth" and "total peace"

A question also arises as to the extent to which the Foreign Minister’s attacks on the transitional justice and his defence of the arrival of the paramilitaries has any relation to the Petro administration’s "total peace" policy, which opened simultaneous peace negotiations with multiple armed groups, including the National Liberation Army (ELN) guerrilla, dissident sectors of the FARC that withdrew from the 2016 peace process, and organised crime groups such as the Gulf Clan. So far the government has offered little clarity on what criminal logic it will apply to each of these groups to achieve their disarmament, including whether it seeks to bring them into the JEP, in the current peace deal.

One more paradox remains up in the air: why does Petro, well remembered for his sharp debates as a congressman on paramilitaries and their political links, now have a Foreign Minister who fiercely defends the bosses of these armed structures?