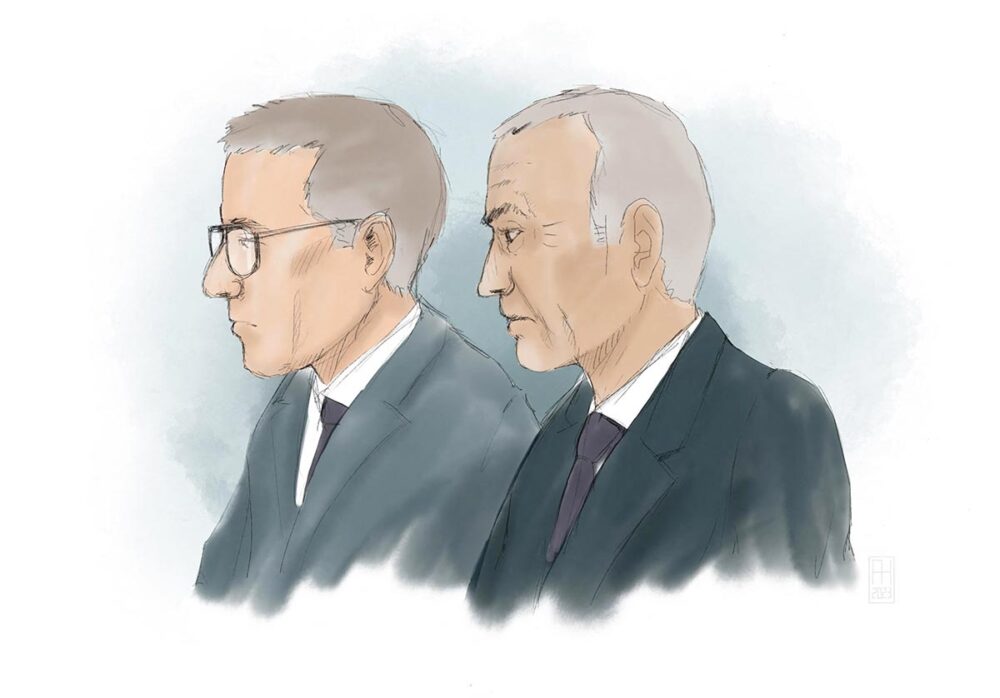

In the nearly six months since it began at the Stockholm court, the Lundin trial has settled into a routine. Hearings are from Tuesday to Thursday, starting at 9.15am in room 34 on the second floor of the imposing building that was once the Swedish capital's city hall, with a 20-minute break that cuts the morning in two around 10.30am. On Tuesday February 20 -- 64th day of the trial in its week 22 -- Alexandre Schneiter, one of the two accused, goes down to the ground-floor cafeteria like everyone else and orders a latte and a raspberry jam sablé. The man his lawyers present as a geophysicist who became Lundin oil company vice-president in charge of exploration shakes his head in a playful gesture to his lawyers and co-defendant, his former boss Ian Lundin, with whom he is accused of complicity in war crimes in Sudan between 1997 and 2003. The company they ran at the time was engaged in oil exploration in Block 5A, now located in what has since 2011 been the Republic of South Sudan.

But despite its apparent routines, this extraordinary trial - 13 years of proceedings, 80,000 pages of case files, two and a half years of hearings scheduled - is full of twists and turns, with the prosecutor's sources being called into question. This is particularly true since the lawyers for Schneiter, former CEO of Lundin Oil, entered the fray on Tuesday February 13, following those for former Lundin Oil chairman Ian Lundin, who had been presenting their case for 24 days.

Attacking the credibility of NGOs

On February 20 Olle Kullinger, one of Schneiter's lawyers, continued the systematic attack begun by his colleagues at the end of November. The aim: to discredit the sources put forward by the prosecution, as well as its initial investigation.

Last autumn, the prosecutor was the first to present his version of events. He tried to demonstrate that the fighting in Block 5A was a consequence of the need to secure oil activities in the context of an independence struggle waged by rebels of the Sudan People's Liberation Army (SPLA) against the Khartoum army.

In contrast, lawyers for the two defendants are doing their utmost to prove that the fighting, destruction of villages and displacement of populations resulted from banal stories of cattle rustling between clans, complicated by ethnic rivalries that continued after independence and therefore had nothing to do with the presence of oil and Lundin Oil’s activities. They are also trying to prove that the sources put forward by the prosecutor who initiated this case in 2010, Magnus Elving - interviewed by Justice Info a few weeks before his death on December 23, 2023 - are unreliable.

For example, Kullinger is attacking the NGO Norwegian People's Aid (NPA) and its representative Father Dan Eiffe, who described in a report the consequences of the bombing of a village in Rier in May 2002. At the time, NPA reported 15 dead and many wounded after an Antonov 32 dropped 16 bombs. The NGO went to evacuate the wounded. On the same day, Eiffe had sent this information to John Ashworth, a Catholic priest involved in the work of a charity organization in Sudan, information which was subsequently taken up in various NGO reports over the months. The lawyer asserts that Eiffe, nicknamed "Commander Dan", was loyal to the SPLA armed rebellion. The defence concludes that any information bearing his mark must be considered as under rebel influence.

The defence is also targeting the "Unpaid Debt" report -- written by Egbert Wesselink and published in June 2010 by the European Coalition on Oil in Sudan (ECOS), an alliance of NGOs -- on (among other things) Lundin Oil's activities in Block 5A between 1997 and 2003, the period covered by the current trial. This report played a decisive role in bringing Lundin Oil's directors to the dock.

The Unpaid Debt project began in 2006, notes Schneiter's defence, through an organization based in the Netherlands. In March 2010, a complaint was filed in Stockholm by lawyer Steen de Geer, also a director of Avocats sans frontières, who had been consulted by ECOS on the legal course of action to take. A few weeks later in May 2010, notes the defence, ECOS filed its own complaint in Sweden, enclosing the Unpaid Debt report. Then, on June 21, 2010, the Stockholm public prosecutor's office took the formal decision to open a preliminary investigation. Prosecutor Elving immediately issued a press release, in which he justified opening the investigation by citing information contained in the Unpaid Debt report and did not cite Lundin.

Attacking the investigation’s impartiality

To support its case for links between the NGOs and the prosecutor, the defence showed on the room's four screens excerpts from e-mail exchanges dating from 2010 between prosecutor Elving and Wesselink, in which the latter explains that the political leaders of the future South Sudan were following legal developments in Sweden on the Lundin case and were ready to help the prosecutor. This was just a few months before the referendum on South Sudan’s independence to be held in January 2011.

The defence took up another e-mail from Elving to a Swedish lawyer, which it has already used several times. "I need information to help me find the way forward - what I'm looking for are arguments in favour of a future strategy," the prosecutor wrote on September 20, 2010. The investigators read the entire ECOS presentation and found nothing tangible. (...) The problem, according to Stig [a Swedish police officer], is that there are no concrete links between the criminal attacks in Sudan and the oil operations. (...) My personal approach, as I said at the Utrecht meeting, is to try to find a temporal and geographical link between the 65 criminal attacks (which can be found in table form in Unpaid Debt) and Lundin Oil's oil exploration/drilling, road building, etc."

After a further deterioration in the situation on the ground, which prevented Swedish investigators from going to the site, the investigation focused on finding witnesses, say Schneiter's lawyers. They refer in particular to an e-mail of March 7, 2014, in which Wesselink told Elving he would come to Sweden and tell him who could be of interest as a witness.

Sources with their “own interests”

“Our aim is not to say whether someone did their job well or badly," Kullinger tells Justice Info. “But the question that must be asked is whether the result of the investigation that was carried out is reliable. And we think that if you allow yourself to be influenced or if the information comes from sources who have their own interests, that goes to the very heart of assessing the reliability of evidence in a criminal case."

In short, the defence criticizes the prosecution for developing a plea instead of focusing on the facts. “It's important to try and investigate what actually happened," continues the lawyer. “We don't think it's possible to have a criminal case based on generalization, and that's one of the main weaknesses of the prosecution."

We will have to wait until mid-May for the prosecution to complete its presentation of the facts, and then witnesses are to be heard until the end of the year.