JUSTICE INFO IN-DEPTH INTERVIEWS

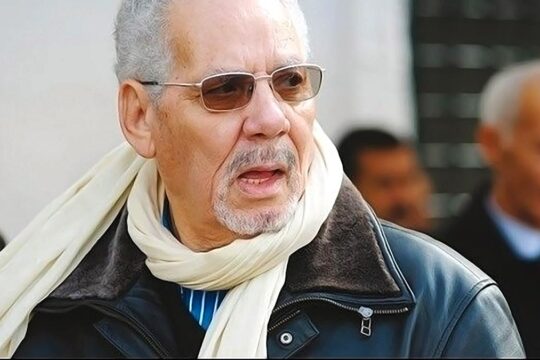

Catherine Marchi-Uhel

Head of the International, Impartial and Independent Mechanism (IIIM) for Syria

Catherine Marchi-Uhel of France is the first head of the first UN evidence-gathering mechanism, the International, Impartial and Independent Mechanism (IIIM) for Syria, created in 2016 in Geneva. After seven years in office, she will be retiring at the end of April. Are such institutions just a cosy, expensive UN job for international jurists, or real value-added in situations of serious international crimes where there is geopolitical blockage on accountability? In an exclusive interview with Justice Info, Marchi-Uhel gives her perspective on this, and on lessons learned at the IIIM.

JUSTICE INFO: You have headed the International, Impartial and Independent Mechanism (IIIM) for Syria since 2017 when it was set up, and now you are leaving at the end of April. Can you say why?

CATHERINE MARCHI-UHEL: My last day in office is April 30 this year. I am leaving for private purposes of retirement and spending more time with my family in France. Also, having worked in international law since 1998 and ten years before that in France as a judge, I have reached a point in my career where I think I have probably done enough. It’s also ending on a stimulating, inspiring note, because the work that we are doing and that my colleagues will continue doing for the Syria Mechanism is extremely interesting and important.

The Syria Mechanism was the first of these new UN evidence-gathering bodies. What is your analysis of how it has performed so far?

I think we can say it has achieved a lot already in circumstances where there are limitations, obviously. We do not have any access to Syria – the Syrian government has declined our repeated attempts to engage –, so that is a serious limitation. Fortunately, many organizations have been documenting crimes committed in Syria since 2011 and have become the main sources for our comprehensive collection, preservation and analytical work. You have a very courageous Syrian civil society, and some of them have exfiltrated documents – like the Caesar Files but also government documents –, preserved videos, done analysis. Of course these crimes occur at a time when everyone has a smartphone, including in Syria, so you have a lot of documentation by way of videos, images being put on social media or saved on hard drive. Among our key sources, you also have Member States, international organizations and UN entities such as the commission of inquiry, mandated by the Human Rights Council as early as 2011 to document the crimes, and it has issued numerous reports.

We have received to date 356 requests for assistance from 16 jurisdictions. This relates to 265 distinct investigations and we have been able to support 174 of them."

Your annual budget is around $25 million including voluntary contributions, and the results of the Mechanism’s work are not necessarily very visible to the average person. How do you justify your value?

I think it’s becoming easier and easier to justify the value. You are right that the results were not very visible especially in the early days, but they are becoming more and more so. Let me give you some figures to get a sense of the direct use of the Mechanism in concrete cases: we have received to date 356 requests for assistance from 16 jurisdictions. This relates to 265 distinct investigations – some investigations are lengthy, complex and lead to more than one request for assistance – and we have been able to support 174 of them. This is concrete support by way of sharing evidence, providing statements of witnesses that we’ve identified and interviewed, developing and sharing dedicated analytical work.

One example is geo-locating crime scenes, also sharing analytical work that we have developed not specifically for one investigation but with a view to support more than one. A classic example of that is the evidentiary modules that we develop so prosecutors that intend to charge war crimes or crimes against humanity for acts committed in Syria are able to rely on briefs that establish, for instance, the existence of an armed conflict.

Now we see concrete cases – in France, in Germany – where this material is relied on for prosecutions, and we have had some judgments already. We also developed a module on systematic attack by members of Daesh against the civilian population. It has been relied on in cases that led to judgments in Sweden, and it’s part of the Lafarge case in France.

The direct contribution to ongoing investigations is one thing. With the Syrian situation – such a long lasting conflict that is not over, such a large amount of perpetrator groups – it is clear that national jurisdictions alone will not suffice. So we are also keeping an eye on what the mandate says, which is to support courts now and in the future.

We decided to have specific lines of inquiry: one focusing on crimes in detention and the system of detention; one on unlawful attacks ; and the third one focusing on crimes attributed to members of Daesh. I have no doubt that all of that would be extremely useful to a prospective prosecutor."

Let’s say that in a number of years the International Criminal Court (ICC) is seized of the Syrian situation, or that an international tribunal is created to deal with the Syrian crimes. What do we want to have achieved so that the prospective prosecutors can really fast track their work? One could say that the centralized pieces of evidence are already great. We use a lot of the funds to make them more searchable. We also decided we were going to have our own structural investigation covering the entire situation of Syria but, in order to prioritize the work, zooming in on specific areas. We decided to have specific lines of inquiry: one focusing on crimes in detention – torture, enforced disappearance – and the system of detention; one on unlawful attacks, with a particular focus on use of chemical weapons but also attacks on medical facilities; and the third one focusing on crimes attributed to members of Daesh. I have no doubt that all of that would be extremely useful to a prospective prosecutor.

As a former judge, is it not frustrating to have to rely on other people, other jurisdictions, to actually bring cases?

No, I don’t find it frustrating. In fact I find it fascinating not to be limited to one jurisdiction and be a justice facilitator. The problem with national jurisdictions is that in most cases you are not going to be able to go after those most responsible. I won’t lie, I wish we had an additional piece such as an international tribunal to promote a more comprehensive solution. That being said, I am not frustrated because this unique value that we bring is really justice facilitation, the use of every justice opportunity. The core of the work is clearly criminal justice, but as we know, justice is not limited to criminal justice, and I’ll give you two examples of that.

I am sure you’re aware of the initiative by the Netherlands and Canada to allege violations of the Torture Convention in Syria at the International Court of Justice. We saw that we could potentially help a case like that, but we wanted to know: does it make sense for victims of torture? Do they see us as having a role to play there, or do they want us to use our resources for only criminal cases? And the consultations that we did with victims’ and survivors’ groups clearly showed they saw this as a very important, symbolic part of the justice response. We are in the process of preparing a report which will be made public and which can be used in this case.

We know from past experience how much information gathered by prosecutors and now bodies like the IIIM could be relevant to the search for the missing."

Another example is the situation of missing persons. We know from past experience how much information gathered by prosecutors and now bodies like the IIIM could be relevant to the search for the missing. So we thought: can’t we be a bit more proactive, rather than waiting years for institutions to come to us and ask to access the archives? We started very early on to identify that kind of information, and started sharing it with the International Commission for Missing Persons (ICMP), with which we have a Memorandum of Understanding. We are also prepared to share information with the new UN institution on missing persons in Syria that is being set up on the initiative of victims and survivors.

You say in your reports that there are internal reviews, reviews by the UN and also independent reviews of your work. So how is the IIIM’s work evaluated, and on what criteria?

We have had our first evaluation by an independent expert, external to the UN, which was finished at the end of last year. The way it’s been done is obviously by speaking to people inside, but also contacting competent jurisdictions that have access to our services, contacting members of civil society and so on.

Is this evaluation publicly available?

It’s not publicly available, it’s really a tool for us to identify areas where we think we can do better, to take action, and to see the assessment.

We had question marks when we started. Are existing jurisdictions going to rely on the evidence provided? Will they make use of our analytical work? The answer to that is yes."

Do you think there are lessons from the IIIM for other UN evidence-gathering bodies like for Iraq and Myanmar?

I think one of the first lessons learned is that there is a need. We had question marks when we started. Are existing jurisdictions going to rely on the evidence provided? Will they make use of our analytical work? The answer to that is yes.

A second lesson is that there is also room – and I think we have demonstrated it – for a mechanism like the IIIM to adopt innovative and inclusive approaches when it comes to working with civil society, recognizing the place of victims and survivors. As you know, I have worked in tribunals and I haven’t seen that level of engagement before. It wasn’t a given. Engaging with them in the way we do and considering that they have agency and they have something to say outside of the evidence-gathering purpose, that’s something really innovative and that’s something we should be proud of.

A third lesson – and it’s another form of innovation – is that we have been really pioneering the use of information management techniques and tools to support investigations into core crimes.

So those are the positive lessons. What about the challenges?

Issues of witness protection arise immediately. People who decide to come forward as witnesses face security issues, and we see it in Europe with some of the trials. So one of the challenges is that we are an institution that cannot on its own provide protection. We can take protective measures, but providing protection for someone who is in danger physically, or their family, we can’t do that. We rely on States for their cooperation in this respect, and that is not easy.

Then the resources are significant, yes, but we don’t have any guarantee of being able to add to the regular [UN] budget. With other crises, Syria is maybe becoming lower on the agenda of some States, and we see that the voluntary contributions are not coming forward as we would need. So an additional challenge is going to be: how can you maintain the level of work with potentially less resources? We are trying to convince the UN and the General Assembly that it’s worth adding to the regular budget – and in the current climate, you can imagine it’s not easy – and we are trying to convince our donor country voluntary contributors that yes, they have already put a lot of money into this institution but if they really want to continue to maintain the said level of support, well that has a cost.

If the ICC were to be seized of the Syria situation, to be honest I think you would probably still need a mechanism like this one, because the ICC couldn’t take more than a handful of cases."

The mandate that was given by the UN General Assembly does not put a time limit on the Mechanism. What is your view on how long the IIIM will or should exist?

It’s difficult to know, but based on past experience, clearly the Syrian situation will generate work for many more years, and we’ve seen with former Yugoslavia and Rwanda that these cases are not over. After two international tribunals, national jurisdictions still have cases. I think what could change is if a dedicated tribunal was established, which might become the repository of all the work that has been done and could be the one that is helping national jurisdictions. If the ICC were to be seized of the Syria situation, to be honest I think you would probably still need a mechanism like this one, because the ICC couldn’t take more than a handful of cases, given the amount of other situations it has. I think it was very clever of the General Assembly not to put an end date.

Interviewed by Julia Crawford

Catherine Marchi-Uhel is Head of the International, Impartial and Independent Mechanism to Assist in the Investigation and Prosecution of Persons Responsible for the Most Serious Crimes under International Law Committed in the Syrian Arab Republic.