“Welcome to Muhanga Correctional Facility!” With these words, a sergeant interrupts a guard trying to hassle the visitor. As you pass the large entrance gate, the eye and ear are drawn to colourful displays -- pink, orange, khaki in places. The atmosphere is calm, clean and busy. Were it not for the guards at the gate, the high walls common to all prisons, and the pink and orange uniforms worn by all prison inmates in Rwanda, you'd think you were in an activity centre for free men. From a sewing room on the left, men in pink and orange alternate the vibrations and stuttering sounds of their sewing machines. Not far away, others are sweating, unloading packs of leftover rice from a truck for cooking meals. As we look towards an administrative block, and higher up towards people in white nursing coats, a police vehicle arrives, adding to the spectacle. Handcuffed young men climb out and sit on the floor, queuing up to register as new residents.

But what's inside those high walls on the right as you enter, marked with a “no visitors” sign? There is not a sound. Are they asleep on this muggy early afternoon? Suddenly, as if to welcome the new inmates, voices rise from the walls, chanting in harmony the Rosary of the Seven Sorrows of the Virgin Mary, which we recognize by its lively ritornello: “mother of mercy, keep present in our hearts the sufferings of Jesus in his passion” is sung in full voice at the end of each refrain. From the way these voices rise soft and strong, you'd think this place were a monastery filled with acts of contrition rather than a repository for genocide convicts.

We have obtained permission to visit one of the penitents. Emmanuel Ruzigana, 67, who was mayor of the former commune of Nyamabuye in the former prefecture of Gitarama (central Rwanda), has been living here since 1997, a hundred metres from the office he occupied in 1994. He was sentenced to 25 and then 30 years in jail for genocide by two gacaca [pronounced gatchatcha] courts. “I didn't kill with my own hands, but I killed by my orders and instructions,” admits this self-described “repentant génocidaire”, who says he “sinned by action and omission”.

2,200 génocidaires eligible for reintegration in 2024

Here in Muhanga, as in the other correctional centres, ordinary prisoners and “génocidaires” live together, warns Alex Murenzi, the facility's director. “So there's no discrimination,” he says, “because they live, eat, sleep and pray together, and share all day-to-day activities.” Out of a total inmate population of 7,346, the "génocidaires" number 737, of whom 728 have been sentenced - including 71 to life imprisonment. As there is no statute of limitations for genocide, nine have been arrested recently and are awaiting trial. Of all those detained for genocide, “653, or 89.7%, are eligible for release at different times, depending on their date of conviction”, explains the director of the Muhanga detention centre.

According to the Rwanda Correctional Service (RCS), out of a total prison population of 87,621 recorded in the country on February 12, 2024, 18,810 (21.4%) are being held for genocide, including 6.3% women. Of these "génocidaires", 4,339 (23.06%) - including 1.7% women - have been sentenced to life imprisonment. Thus, those eligible for release after serving their sentences number 14,471. And, according to the SCR, almost 2,200 prisoners will be released throughout the country in 2024 alone. Many have already been released in the last 12 years. In 2012, the same official service counted 39,572 people convicted or awaiting trial for crimes committed during the Tutsi genocide in 1994.

Muhanga CF Sector

Muhanga, known as Gitarama until 2006, is a district in Rwanda's Southern Province. This is the name of its capital, and the name of the local prison is Muhanga Correctional Facility (Muhanga CF, for short). For its inmates and the prison administration, the “Muhanga CF sector” is a separate administrative entity, located near the middle of the imaginary “Mu Cyakabiri” line (meaning “halfway”), which divides Rwanda from north to south.

Ruzigana is thus registered in the village of Ituze, in the Ingenzi cell of the Muhanga CF sector. The administrative organization of this sector is modelled on that of the rest of Rwanda outside. Headed by an executive secretary and a consultative council, Muhanga CF is subdivided into 15 cells and 85 villages. Each entity has its own security officers. Sector managers from the districts of Muhanga, Kamonyi, Ruhango and Karongi, served by Muhanga CF, regularly come here to meet detainees, to keep them abreast of changes in their place of origin, and to help them settle certain matters such as land issues.

“This territorial organization of the correctional centre, the family visits, meetings with local authorities and resolution of their problems all help prepare them for the changes that have occurred during their long absence, and for their reintegration once they are released,” says prison director Murenzi.

"The sentence is light compared to my crime"

How do these convicts cope with their sentences and imprisonment? When one court gave Ruzigana 25 years and then another gave him 30 years, he was desperate, he says, and found the sentence “too heavy to bear”. But then as time went by, he explains, “I realized that I was rather lucky, because compared to the crime of genocide, I thought my sentence was quite light”.

In retrospect, the 60-year-old still doesn't understand how everything turned bad. “I had visited Israel and the Shoah Memorial,” he recalls. “I had a Tutsi wife, in-laws, friends. But evil prevailed over good, and I regret that.” When the interim government of Jean Kambanda, prime minister during the genocide, moved into his commune of Nyamabuye in Gitarama in April 1994, he says the best thing to do would have been to flee with his family. “But instead, I adhered to his genocidal plan,” he confides, giving orders to organize patrols and erect roadblocks where Tutsis were killed.

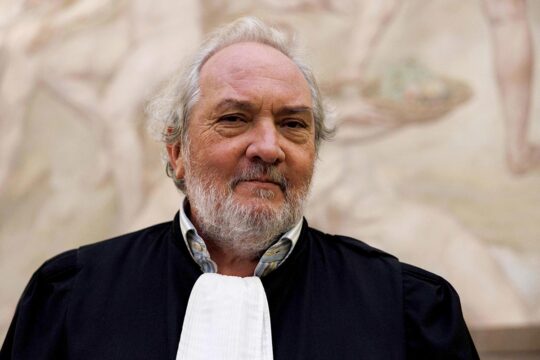

Ruzigana tells us that afterwards he felt the need to clear his conscience. He felt it was his duty to testify against members of the interim government but, he says, “I couldn't do that without having pleaded guilty myself”. This he did before various gacaca courts in 2010. Later, before the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR), he testified for the prosecution in several cases, including in 2011 in the case of Callixte Nzabonimana, a native of the same Gitarama prefecture and formerly local president of the ruling MRND party.

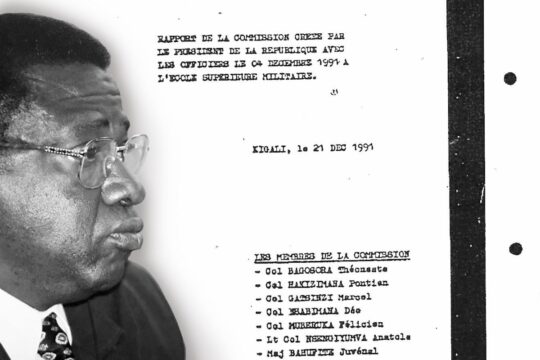

On April 12, 1994, the interim government formed after President Juvénal Habyarimana’s assassination left the capital Kigali, fleeing the advancing rebels of the Rwandan Patriotic Front, currently in power. It settled in Gitarama during the genocide.

Who are they?

According to the SCR, the prison population reflects all components of society, from the elite to the least educated, who are the most numerous. There are prefects, sub-prefects, mayors, military personnel of all ranks, magistrates, teachers, doctors, pastors, priests, businessmen, journalists and poor smallholders (the majority).

Only one member of the interim government, Agnès Ntamabyariro, has been tried and convicted in Rwanda, while 15 other ministers were tried at the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR). Arrested in Zambia on May 27, 1997 then extradited to Rwanda, Ntamabyariro spent ten years in pre-trial detention before her trial began. On January 19, 2009, she was sentenced by the Nyarugenge High Court in Kigali to life imprisonment. Along with Valérie Bemeriki, a journalist with the notorious Radio-télévision des mille collines (RTLM), Ntamabyariro is one of 77 women sentenced to life imprisonment for genocide in Rwanda.

In Rwandan prisons, those who have pleaded guilty live together with those who have not. Those who have not pleaded guilty return to the community in the same way when they have served their sentence.

A prisoner's long day

The days are long, especially for those serving long sentences, say Ruzigana and his fellow inmate Moïse Nsengimana. The inmates get up at 5.30 am and go to bed at 9 pm. In between, every minute is punctuated by a tightly regulated schedule: ablutions, breakfast of porridge at 6 am, various jobs including outside the prison, medical care, various clubs, rest or social visits, meal from 3 pm to 5 pm, sport, prayers, TV. And at 9 pm, everyone goes to bed, except when there's permission to stay up for an event like a big soccer match.

There are more special days, like Saturday, which is the day for flash visits, or Sunday for team sports. On Wednesdays from 10 am to 1 pm, the entire Muhanga CF area, open to the general public, is abuzz with cultural and artistic displays. This is conference day. It is also the day for family visits of up to an hour, during which family issues are discussed and settled. For some, this day is too short, but for inmates who have no one to see it is unfortunately too long.

Are they sufficiently prepared?

It would seem that for Ruzigana and all those who pleaded guilty, in the presence of their families, the problem of reintegration does not arise. But it may be more complicated for those who pleaded not-guilty, such as fellow prisoner Nsengimana, who was sentenced to 15 years for “the death of an unidentified person”, he says, near a roadblock he was manning with others. His only fault, he believes, was “being in the wrong place at the wrong time”. He describes the early days of his detention as harsh. The days were interminable.

But a year from the end of his sentence, Nsengimana claims to have changed. While “unity and reconciliation” clubs and “civic education” sessions have contributed, as well as Christian organizations like Prison Fellowship and Justice and Peace, Nsengimana says there is also another key factor. “Time heals and cleanses our brains,” he explains. However, he believes that “a person who committed genocide deserves support, once he or she has returned to society, to help them gradually learn to live again”. He stresses the importance of support “to help them understand and resolve family problems that may lead them to commit new crimes” - problems linked in particular to what may have happened during their detention.

“We’ve become wise with age”

Alexandre Kayiranga, a common law prisoner, is one of the leaders in Secteur Muhanga CF and one of Ruzigana’s circle of friends. “These people are so impressive with their discipline and friendliness that it's hard to believe they committed genocide,” he says. He points out, however, that many of those who never receive visitors “need love, moral support. Otherwise they risk depression and may be inclined to commit new crimes”. According to Kayiranga, those convicted of genocide are the calmest. They are also the least tempted to escape and the most willing to take responsibility.

Thirty years on, according to former mayor Ruzigana, most of those convicted of genocide are getting on in years. And what's more, “we've become wise with age, and the consequences of what we did on our Tutsi neighbours, our families and above all ourselves have taught us some inescapable lessons”, says the elderly Ruzigana. “The fact that the crime of genocide has been punished for the first time in Rwanda is in itself an indelible lesson that calls for non-repetition.”