In the run-up to the elections, there was wide popular support for the South African government’s strategy of legal intervention in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, following victories in a case closely followed by South African media. But on May 29, the African National Congress (ANC) lost its absolute majority, winning just 40% of the vote in a disputed election campaign.

The party, which has been in power since Nelson Mandela’s first democratic election to the presidency in 1994, has been unable to secure employment for everyone, with unemployment running at 33%, and 45% among young people. It remains unable to ensure a continuous supply of electricity and unable to curb corruption, perceived by 81% of the population as widespread.

Referral to the ICC and ICJ

On the judicial front, South Africans welcomed two big pieces of news in the week leading up to the vote. On Monday May 20, the prosecutor of the International Criminal Court (ICC) requested arrest warrants for Israeli Prime Minister Benyamin Netanyahu and his Defence Minister Yoav Gallant, as well as for three Hamas officials. South Africa made its contribution to the process on November 17, when it lodged a complaint with the ICC along with four other states: Bangladesh, Bolivia, Comoros and Djibouti. Based on the referral filed by Palestine in 2018, the South African application used the term “apartheid” to designate Israel’s occupation policy in the Palestinian territories.

Four days later, on Friday May 24, the International Court of Justice (ICJ) ordered Israel to “immediately halt its military offensive” in Rafah. This decision was the fourth taken by the UN court in The Hague after South Africa initiated proceedings against Israel on December 29, 2023, under the Genocide Convention for its action in the Gaza Strip. At South Africa’s request, the ICJ had already demanded on January 26 that Israel do everything in its power to prevent acts of genocide in the Palestinian enclave and on March 28 that it allow humanitarian aid in.

Shared experience of apartheid

The legal team South Africa sent to the ICJ is headed by professor of international law John Dugard, who has served as an ad hoc judge at the ICJ and as UN Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in the Palestinian territories (2001-2009). His team, made up of nine jurists representing all the cultural components of the rainbow nation, is led politically by Vusi Madonsela, South Africa’s ambassador to the Netherlands.

“South Africa has referred to the ICJ and the ICC because it thinks it bears a special obligation to its own people and to the international community as a whole to ensure that wherever the egregious and infamous practices of apartheid occur, these must be called out for what they are, and brought to an end immediately,” Madonsela explained at a colloquium in February at the European Parliament in Brussels. “South Africans have the direct experience of international solidarity and of the importance of multilateral institutions, particularly the United Nations: our own liberation from a brutal apartheid regime was in large part enabled by the commitment of allies and friends in our struggles within these institutions. In this history, the Palestinians have steadily remained allies.”

Two closely linked liberation movements

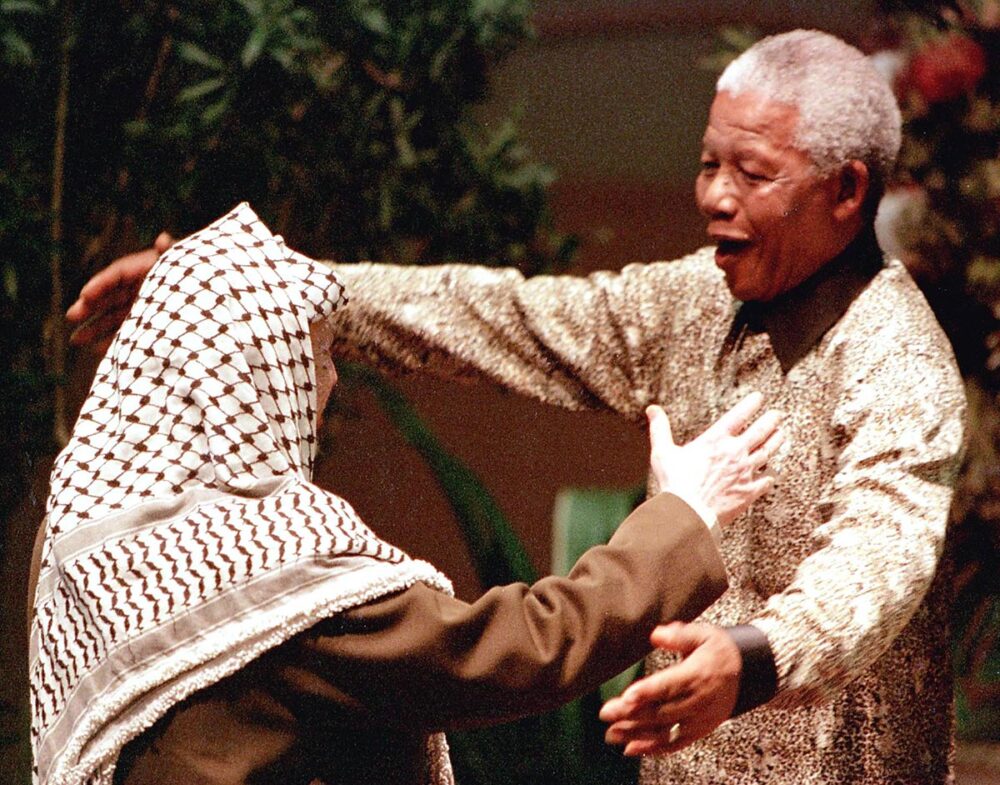

“The struggle for liberation, for sovereignty, for self-determination of Palestinian people and the liberation movement in South Africa have always been closely twinned,” confirms Nicole Fritz, former director of the Southern African Litigation Centre and the Helen Suzman Foundation, two of southern Africa’s leading human rights NGOs. “From the earliest days, there have been an understanding, a recognition of each other, solidarity and support from the early days, until the end of Apartheid.” In 1948, when Palestinians were dispossessed of part of their land following creation of the State of Israel and the first Arab-Israeli war, black South Africans were victim the same year of a general policy of expulsion from their land after the accession to power of the National Party, which instituted apartheid. In the 1960s and 1970s, armed struggle was organized in Palestine and South Africa, in the face of oppressive states.

“In 1977, the 2nd Additional Protocol to the Geneva Conventions was introduced by the Red Cross to protect the fighters [and the victims] of non-state armies, as a result of advocacy by the ANC and PLO (Palestine Liberation Organization),” observes Fritz. The brutal repression of black teenagers’ revolts in the streets of Soweto from 1976 onwards was followed by that of Palestinian teenagers during the first Intifada in 1987, while the political leaderships of the ANC and PLO were in exile in Lusaka (Zambia) and Tunis (Tunisia) respectively. These repressions, shocking in the eyes of the world, both triggered peace processes in the early 1990s.

But only the South African process led to democratic elections in 1994, while the Israeli-Palestinian peace process remained bogged down. In a famous speech in Pretoria in 1997, Nelson Mandela deplored the stalemate: “We know too well that our freedom is incomplete without the freedom of the Palestinians.”

Legal activism

This shared history largely explains South Africa’s legal activism in recent months, which may seem surprising given its previous procrastination vis-à-vis the ICC. In 2015, under President Jacob Zuma, Pretoria failed to arrest former Sudanese President Omar Al-Bashir, who was under an ICC arrest warrant and came to attend an African Union summit in Johannesburg. In 2016, South Africa announced its intention to leave the ICC, leading a chorus of African countries. Only a decision by the South African High Court was able to prevent this. In August 2023, under the current presidency of Cyril Ramaphosa, South Africa again announced its withdrawal from the ICC, before changing its mind and inviting Russian President Vladimir Putin to speak at a BRICS summit via video-conference.

For Nicole Fritz, as well as other observers in Johannesburg and Pretoria diplomatic and human rights circles, one man “has been critical to the ICJ initiative and a much more engaged posture on the part of South Africa in global institutions of justice”. This jurist, Zane Dangor, was appointed Director General of the South African Department of International Relations in April 2022 and his name is on everyone’s lips. Right-hand man to Minister Nadeli Pandor, this senior ANC loyalist is present in The Hague alongside Vusi Madonsela at all ICJ hearings. In 2016, while serving under the Zuma administration, he publicly protested against his government’s policy of turning its back on the ICC. Architect of the current legal commitment to the Palestinian national movement, he gave the key in a text published in December 2023 in the South African online newspaper Daily Maverick: “The West’s misguided acceptance of the actions of the Israeli government has to end for a just and lasting peace to be realised.”

On May 29, the ballot boxes spoke, and speculation is running high. The ANC retains a relative majority, but will now have to find a coalition partner. It probably won’t be Jacob Zuma’s Umkhonto We Sizwe, although it is considered a big winner in this election. Perhaps it will be the Economic Freedom Fighters of the unpredictable Julius Malema, or more likely John Steenhuisen’s Democratic Alliance, to which the ANC might be tempted to add the Zulu movement Inkhata Freedom Party. “I do not think that any coalition will change South Africa’s approach regarding the Palestinian cause,” commented Fritz after the election. “I anticipate a minority government with confidence and support being offered by other parties such as the Democratic Alliance.”