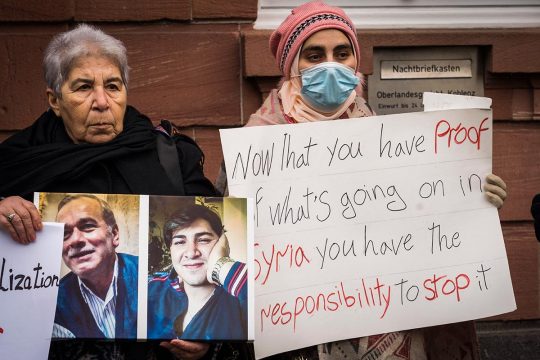

Over the past four years, the German judiciary has realized a number of premieres in the field of universal jurisdiction: the first trial dealing with Syrian state torture as a crime against humanity, the first trial to define the Islamic State's (IS) attack on Yazidis in Iraq as a genocide, and the first trial to hold a member of the Gambian killing squad, the Junglers, accountable.

But being the first also means sometimes going forward without a clear path and making mistakes on the way. The trials in Koblenz, Frankfurt, Celle, and other German cities have exposed shortcomings in the German Code of Crimes Against International Law (CCAIL) that has never been changed since its introduction more than 20 years ago. Through trial and error, it has become clear that several amendments are needed if Germany wants to use universal jurisdiction as a meaningful tool against the most serious international crimes.

In 2023, inspired not only by past trials but – perhaps mostly – by the war in Ukraine and the potential for legal intervention, the German ministry of justice set out to “close gaps in criminal liability and strengthen the rights of victims of crimes against international law”, as Justice Minister Marco Buschmann proclaimed upon presenting the draft law about a year ago. Now, in June 2024, the German parliament passed the reform law. The changes have indeed strengthened victims‘ rights and dealt with some of the most criticized issues of the past years, such as translation and recording, or the definition of enforced disappearances. Victims’ rights representatives, however, argue that the reforms do not go far enough, and that some of them even restrict the participation of those seeking justice.

A step forward for translation and recording

Looking at the main changes of the CCAIL reform means revisiting Germany’s most prominent universal jurisdiction trials of the past years. Every part of the reform is connected to issues and debates that emerged through one or more of these trials. One of the biggest points of criticism has been the lack of translation and recording. Media representatives and civil society were not able to follow the proceedings if they did not speak German. And no one outside the courtroom in Germany could follow the trial, since German trials are usually not filmed nor recorded.

This meant that affected communities around the world had extremely limited access to the trials that concerned crimes in their countries, by and against their fellow citizens. This absence of access undermined the potential of legal accountability to facilitate political and societal transformation processes. For how can a society heal, learn, move forward from conflict, when justice is done in a far off place in a foreign language?

The new CCAIL states that courts “may” allow recordings of proceedings of “outstanding contemporary significance”. Before the reform, that significance had to be connected to Germany, while now a historical significance for Syria, Gambia or any other country would suffice. Courts “may” also allow media representatives who do not speak German to make use of whispered interpretation or to access existing interpretation that is usually provided for the witnesses, plaintiffs and defendants. This was a huge point of conflict during the Koblenz trial, where Syrian journalists and trial observers filed two complaints trying to gain access to the court-provided translation service. The Federal Court of Justice (Bundesgerichtshof – BGH), Germany’s highest court of civil and criminal jurisdiction, finally decided that accredited journalists should be allowed to listen to the translation via headsets, but the deadline for accreditation had long passed at that point...

After the reform, translation access will be available to media representatives, but not to the public. Still, these two changes regarding translations and recordings are a major victory for all those who have been fighting for easier access over the past years. The law says that courts “may” allow recordings and access to translation, which leaves the decision at the discretion of the judges. “We would have preferred a more definite wording in the legal text,” says lawyer Patrick Kroker from the European Center for Constitutional and Human Rights (ECCHR), who has represented victims in the Syria and Gambia trials. But he is not too worried, since the explanatory addition to the law clarifies that recording and translation should be the norm, provided there are no important reasons to the contrary. “They are afraid of the technical issues,” believes Kroker. “And in case a witness is intimidated by the recording, they need a way to opt out.” Kroker, who participated in the reform negotiations as an expert, observed that “those who are part of or close to the judiciary were trying to streamline these processes as much as possible, while those focused on outreach and advocacy [such as the ECCHR] tried to go further.”

Facilitating prosecution of enforced disappearances and sexual violence

Another major change relates to the crime of enforced disappearance, that has long been underrepresented in German law. Until recently, it was not part of national law at all, despite Germany’s obligations since 2009 under the UN convention against enforced disappearances. The CCAIL did define the crime of enforced disappearance, but required that someone had made a formal inquiry into the whereabouts of the disappeared person without receiving that information from the authorities in charge. But hardly anyone would dare to formally inquire into the whereabouts of a disappeared person in a dictatorship like Syria, because that, as many witnesses have described, would most probably lead to their own arrest, torture, or even death.

As a consequence, the crime of enforced disappearance was not charged at all during the Al-Khatib trial, even though all of the victims had been forcibly disappeared prior to their incarceration and torture, and it had become clear throughout the hearings that the total lack of knowledge on the whereabouts of loved ones was among the most painful experiences Syrians went and still go through under the Assad regime. And yet, the prosecution knew that it would be near impossible to prove this crime, due to the requirement of a formal inquiry. In future trials, this will not be an obstacle anymore.

Most of the commentators of the reform praised two further changes in the law: first, the crime of sexual violence as a war crime and crime against humanity was adjusted to comply with the Rome Statute. This meant, among other details, that sexual slavery has been included and the term “sexual coercion” has been replaced by “sexual assault”. In addition, persecution on grounds of sexual orientation has been defined as a crime against humanity.

Secondly, the law now clarifies that foreign state officials cannot invoke functional immunity when charged with international crimes by the German judiciary. In practice, this was already the case before: based on customary international law, the authorities justified the right to prosecute state officials regardless of their rank. Still, in 2021 and again in 2024, the German Federal Court had to step in to decide that an Afghan and a Syrian national could, in fact, be prosecuted for alleged international crimes. From now on, the law provides certainty.

Easier access for plaintiffs, but less rights?

While some changes are clearly for the better, others are more controversial. With this reform, victims of crimes against international law are now able to join proceedings as plaintiffs, which comes with the right to legal assistance and psychosocial support. Joint plaintiffs did participate in past trials, but they were not admitted as victims of crimes against humanity or genocide, but as victims of the crimes against national law that coincided, such as homicide, rape or severe deprivation of liberty. But even though this will change in the future, the new law holds quite a few restrictions.

“They opened the gates for plaintiffs to join these trials, but limited their possibilities on the inside,” says Kroker. For example, plaintiffs will not have the right to hold closing statements, although the court “may” still allow them to do so. Looking back at the Koblenz trial, it seems that those personal statements were one of the most important parts of the trial for many of the plaintiffs, a crucial step in their healing journey. It remains to be seen, how strict courts will be when it comes to letting victims speak.

In addition, the new law forces joint plaintiffs to share one lawyer, if they were injured within “the same circumstances of life”. This could, for example, mean being victims of the same crime against humanity, or being women and victims of sexual violence, etc. In Koblenz, this could have meant that one lawyer would have had to represent around twenty plaintiffs. This could make the work of victims’ lawyers like Kroker very difficult, he said. According to him, this step was inspired by the system of common legal representatives at the International Criminal Court; but lawyers in Germany will not have the budget to hire a whole team to support them, he worries.

Finally, not all crimes defined in the CCAIL qualify victims to become joint plaintiffs. “It is incomprehensible why the entitlement to become a joint plaintiff in relation to international crimes has been additionally restricted,” writes ECCHR lawyer Isabelle Hassfurther. “The right to join proceedings is made dependent on the fact that the victims’ rights have been violated in specific legal interests, namely their lives, ‘their rights to physical integrity, freedom or to religious, sexual or reproductive self-determination or, as a child, [their] right to undisturbed physical or mental development’”. This requirement not only excludes victims of psychological torture, but also victims of racial and gender-based discrimination, she says. “We would have hoped for less restrictions regarding the representation of joint plaintiffs and their procedural rights”, says Member of Parliament Helge Limburg, who negotiated the reform as a representative of the Green Party, adding that the judiciary, on the other hand, wanted to avoid lengthy trials. “In the end, we reached a compromise that takes into account the worries of the judiciary regarding the manageability of international trials, as well as the interests of the victims to be heard and to participate individually.”

A successful reform, undermined by double standards?

Despite a number of shortcomings, Kroker, Limburg, Hassfurther, and other politicians and lawyers see the reform as a success. “With this reform, we bolster up our German judiciary that has played a leading role internationally in the implementation of universal jurisdiction over the past few years,” says judge and Member of Parliament Sonja Eichwede, who took part in the negotiations on behalf of the German Social Democratic Party (SPD).

However, with Germany’s recent reluctance to support international proceedings with regards to the war in Gaza, it remains to be seen if the country will be able to keep up that leading role. “It must remain a central concern to ensure the equal application of the law to all and to counteract double standards,” writes Isabelle Hassfurther. The ECCHR lawyer worries that “the legitimacy of the international criminal proceedings that German courts will conduct in the future in application of the new law could be compromised.” Because what has not changed through the reform, is that the German justice ministry has the right to influence the Federal Prosecutor’s decisions on which crimes to investigate. Political considerations are admissible. When the alleged perpetrators are not present or expected to be present in Germany, these decisions can hardly be reviewed or challenged by courts. This has often been criticized but was not debated at all throughout the CCAIL reform.