In October last year, the Prosecutor of the International Criminal Court (ICC) suddenly announced he was withdrawing all charges against Maxime Mokom, former Central African Republic (CAR) minister of Disarmament, during the process of confirming the charges against him, before the judges had a chance to say yes or no to his potential trial. At the time, we wrote “Mokom has been released from prison”. But the details that have now emerged during his application for compensation show how very twisted the route out of the Scheveningen detention unit can be.

The files available on the court website have been redacted to within an inch of their lives to make sure there is no indication about where Mokom tried to go, where he is now, or even where his family is. But the detailed emails going back and forth make up eight separate annexes. In one surreal exchange, who gets to ride in the car to the hotel where Mokom is being held is under discussion. Mokom was not initially “thrown into the road” by the ICC, as Mokom himself told the court, but was placed instead in a “legal fiction” as described by the Registry representative Marc Dubuisson known as the “ICC bubble”. This is how someone who has to leave the detention unit, as ordered by the court, is looked after by the court because there is no state available to which the former detainee can go. The “legal fiction”, outlined Dubuisson, is that a hotel room is in fact part of the ICC. No one – except, as in this case, their birth country – usually wants an international former detainee. So they are stuck in a legal limbo that stops them from coming under the rules of the host state, the Netherlands, who could arrest them as an illegal immigrant who has arrived in the country without documentation.

And so instead, they are in that bubble, while the court tries to find them a new home. Back in the CAR, Mokom had been tried in absentia and sentenced to life or hard labour depending on your sources. So Bangui was out of the question.

Mokom says who failed him

Mokom is claiming “prosecutorial, judicial and administrative negligence”, reminded the court presiding judge Miatta Maria Samba. She’s heading what is known as ad hoc “Article 85 Chamber”, named after the specific provision in the court’s Rome Statute governing compensation for wrongful arrests. “Anyone who has been the victim of unlawful arrest or detention shall have an enforceable right to compensation,” it reads. She's flanked by judges Keebong Paek and Beti Hohler. Hohler has worked at the court for many years but was only recently elected as a judge. Paek is also one of the new cohort of trial judges, sworn in in March this year.

Judge Samba summarised Mokom’s application and the three grounds it comprised. The first was that he was the target of a wrongful prosecution because of the Office of the Prosecutor’s failure to acknowledge or identify exculpatory evidence. Secondly, Mokom alleged failure of Pre-Trial Chamber and the Appeals Chamber to provide timely decisions – twice – which caused him irreparable harm. Finally, administratively, he alleged he was subject to unlawful detention twice: from the day of his application for interim release on 14 November 2022 and his actual release in October 2023 during which he was not granted provisional release because no state were parties willing to facilitate that; then when he was confined to a hotel after the proceedings terminated.

Mokom is asking for 2,850,000 euros in compensation for himself and an additional 500,000 for the harm caused his family.

The procedural history is long and detailed around the period of the withdrawal of charges until Mokom’s departure to a destination undisclosed. But some key points emerged during the day-long hearing on September 9. He spent 43 days in a hotel. His movements were restricted. Everyone – judges, administrators and lawyers – possibly even the states involved, even though they did not appear in court, felt they did their jobs. But there’s nothing in the court’s regulations to deal with this situation well. And the agreement The Netherlands has with the court on the movement of witnesses and detainees also doesn't fully encompass what was happening.

Who was told what when, why Mokom’s lawyers weren’t fully informed, what the Registry said to the host state and back is part of the dispute between the parties – but it’s redacted.

Are international tribunals able to function well?

So why report on these proceedings when they rely on limited documentation and hop in and out of closed sessions?

It’s emblematic of the many issues the ICC faces, where cases take too long to come to court, detainees are arrested long after the alleged crimes, procedures – in Mokom’s case, for example, deciding who would represent him – are tedious, and instructive on whether these international tribunals are in fact able to function well. “Handicapped,” is how Philippe Larochelle, Mokom’s lawyer, described the court in that it couldn’t perform what he described as “the normal functions of a criminal court”.

On the case against his client, Larochelle described the prosecutor’s work in the CAR as “highly unreliable” because, he said, their office is “working hand in hand with one of most corrupt regimes of the planet”. The result of proximity with the country’s president, known as “le soleil” in CAR, said Larochelle, was that “the prosecutor is blinded by the sun”. If the Office of the Prosecutor go after Russian president Vladimir Putin and they are trying to go after the Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, “I hope these warrants are more solid than what they had for Mokom, or they will be in far more serious trouble,” he told the court.

Larochelle also spent much of his allotted time needling at the prosecution’s decision to withdraw charges. If they had had exculpatory evidence among the 30,000 plus documents disclosed to the defence in the end, then why did it take them five years to work that out, he asked. He waved around the Office of the Prosecutor’s code of conduct and quoted large chunks relating to “fairness”.

“In good faith”

Helen Brady, a prosecution appeals counsel, told the court that Mokom’s team were clearly “more than capable of analysing the material” themselves and that Mokom had benefited from “a robust and prepared defence”. But the standard of evidence for an arrest warrant, and that for a confirmation hearing, was different from the prospect of a successful conviction, she told the court. The decision to drop the case was a “forward-looking” assessment, she said, made “in good faith” because, as outlined by the prosecutor, several witnesses – insider witnesses – were no longer available. Further information about issues of cooperation, investigation and the prosecutor’s strategy were not going to be forthcoming because they are “protected’ and not required by the court, she said. She agreed though that her office’s disclosure of material to the defence “had not been perfect”.

For the Registry, Dubuisson said it was not clear exactly on what basis Mokom was making his claim against the court. Article 85, he outlined, does not only deal with compensation for wrongful arrest. In its third paragraph it refers to “exceptional circumstances, where the Court finds conclusive facts showing that there has been a grave and manifest miscarriage of justice”. But Dubuisson said there was no reason to provide compensation on either basis. Instead, he described how much effort the Registry had put into finding a solution but “one cannot ask the registry to endlessly contact states”. The judges of the Pre-Trial Chamber themselves decided “it must ultimately come to an end,” he said.

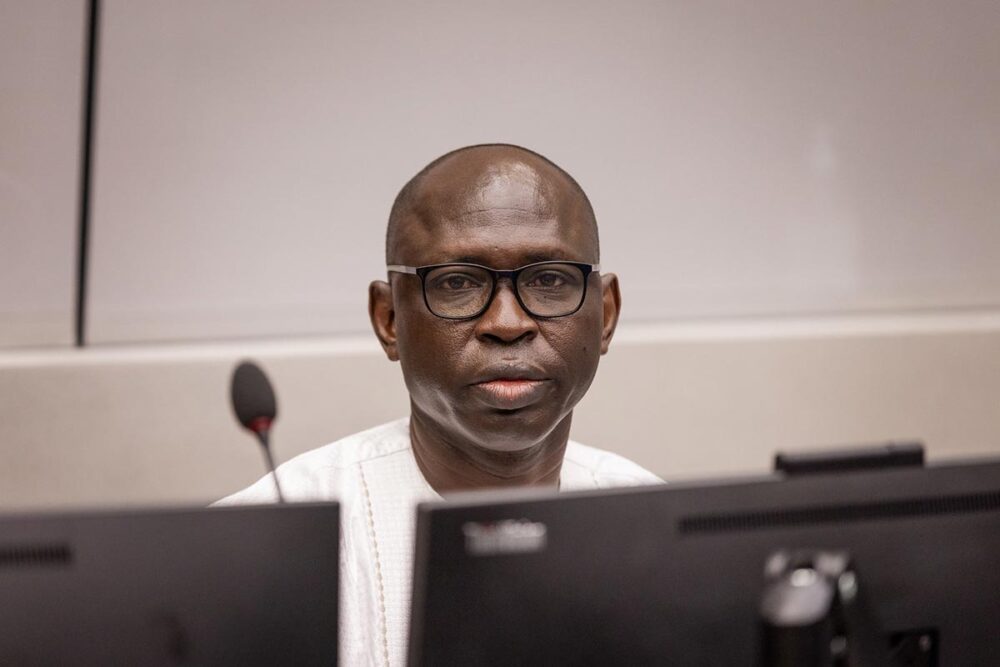

Mokom himself addressed the court. He talked about how his freedom of movement was restricted because he is now applying for asylum in an unnamed state. “I suffer morally and physically,” he said. He also described how the ICC Registry had put up big notices advertising his confirmation of charges hearing in the CAR “suggesting my charges would be confirmed”. Now these allegations are “stuck to my skin,” he said. “I am a Central African great criminal,” this “will never leave me”.

“The court has ruined this man’s life,” concluded Larochelle.