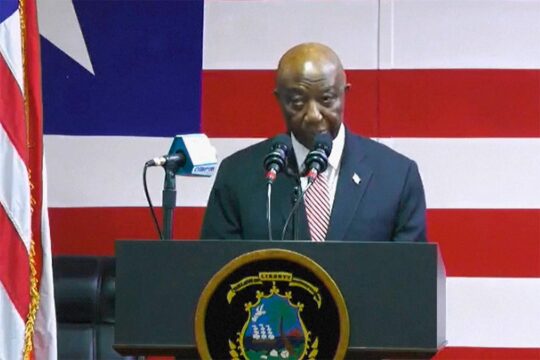

On August 15, 2024, Liberian President Joseph Boakai unexpectedly rescinded his decision appointing Jonathan Massaquoi as the head of the War and Economic Crimes Court (WECC) Office and called for its reconstitution. Before the August 15 Press Statement, an earlier statement was released reaffirming the President’s confidence in Massaquoi, despite opposition by civil society leaders, the Liberia National Bar Association and National Orator for Independence Day on July 26, 2024. The Coalition for Justice in Liberia pointed out in particular that Massaquoi represented the wife of convicted former Liberian President Charles Taylor, which they argue prevents him from ethically representing the WECC Office.

The road less travelled

Regardless of how armed conflicts are resolved, criminal prosecution of war crimes or crimes against humanity are a controversial path to pursue. Some claim that criminal accountability has the potential to roll back early democratic gains or disrupt the transition from war to peace. Some see it as digging up old wounds from which dangerous social memory might fester. Previous Liberian administrations, such as Ellen Johnson Sirleaf’s and George Weah’s have used the politics of silence as a strategy to manoeuvre the politics of transitional justice. When President Boakai declared during his inauguration that he will explore the feasibility of setting up the court and when, in less than four months, he established the office to begin the process, he embarked on a road less travelled.

But embarking on the road less travelled is not an end in itself. What you do on that road is what matters. After tightly fought elections, Boakai has decided to govern by inclusion. In this strategy he has brought together political actors from across the aisle, who brought with them divergent ideological positions on transitional justice. One side is relying on old political networks, outside of the ruling Unity Party, to bolster the President’s strategy. The other side is represented by Boakai’s loyalists who have developed careers in human rights and in the truth and reconciliation process. Both sides, without talking to each other, are seeking to influence the President’s decision on the process. The chaotic decision-making of the last few months is a result of this dynamic in which both sides are attempting to manipulate a particular outcome.

To visualise this elite conflict one should imagine a pyramid where Boakai, the vision bearer of civil war-era accountability, sits at the top, while at the base lie partisan views, feelings of entitlement and a sense of ownership on how a national process ought to roll out. For Boakai to firmly establish his grip on transitional justice decision making, he must first flatten this pyramid and re-establish a centre of gravity where forces with divergent viewpoints can be brought together with a common sense of purpose. Though Massaquoi was not by any stretch of the imagination a human rights lawyer and transitional justice expert, the conflict in the presidency goes beyond his suitability for the job.

The fight by one power bloc to assert control rather than be inclusive and explore a shared national vision in dealing with the past is the actual conflict in Liberia’s transitional justice decision making.

“This cannot be monkey work baboon draw”

The process must also go beyond the presidency to civil society and the victims’ groups, for there too lie its own internal contradictions. Civil society claimed that they opposed Jonathan Massaquoi’s appointment because of his previous role as lawyer for Agnes Reeves Taylor and more recently for Gibril Massaquoi in a defamation lawsuit against Swiss NGO Civitas Maxima, its Liberian partner the Global Justice Research Project and former TRC Commissioner Massa Washington. They say having him stay on would amount to a conflict of interest, given his previous role for two alleged war criminals.

I maintain that the civil society campaign was subterfuge for a hidden agenda. CSO leaders were heard saying, “this cannot be monkey work baboon draw.” In plain English it means we cannot be the ones doing the messy job of campaigning and standing up to perpetrators’ threats and then allow someone from “outside” come and reap the benefits. CSO leaders claimed that the process leading to Massaquoi’s appointment was not consultative and transparent. These CSO leaders were in fact in pursuit of positions, rather than committed to seeing a transparent process. On the question of ethics, members of the Grievance and Ethics Committee of the Liberian judiciary told me that they were confident Massaquoi was not in any breach of ethical standards. In fact, some of them indicated that he is reputable and one of the best in the legal practice in Liberia.

TRC-1 to TRC-2

The sense of entitlement within civil society is somewhat reminiscent of the process leading to the establishment of Liberia’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission 1 (TRC-1) and Truth and Reconciliation Commission 2 (TRC-2).

In February 2004, Charles Gyude Bryant, chairman of the National Transitional Government of Liberia, appointed the commissioners to Liberia’s first Truth and Reconciliation Commission. Bryant was scheduled to participate in a donor conference in Europe and he wanted to project an image of Liberia’s rapid transition from war to peace. With this superficial agenda in mind, he hurriedly put together a Commission that some scholars have named and styled, TRC-1. The process was so rushed and poorly constituted that it did not have terms of reference for the commissioners. Neither did an Act stating its function, power and purpose exist.

In response to this, Liberian civil society leaders convened and established what became known as the Transitional Justice Working Group. The main point of advocacy was to reconstitute the entire process. Out of this, the act creating the TRC was written, and Jerome Verdier, a civil society leader who played a key role in writing the law as well as advocacy, emerged as the putative head of TRC-2.

The civil society advocacy to remove Massaquoi parallels Liberia’s transitional justice history of TRC-1 to TRC-2. In the removal of Massaquoi is the contradiction of CSOs seeking to be both player and referee simultaneously, in the same way that the Bar Association dispatched secret communication to propose to President Boakai its own alternative candidate in the midst of the campaign to remove Massaquoi.

Reconstituting the process

On August 15, Information Minister Jerolinmek Matthew Piah, acting on behalf of President Boakai released a press statement calling for the reconstitution of the leadership of the war crimes court office. In the call for application that followed, two things are critical.

Firstly, the criteria put together is focused on what is described as an “astute lawyer of impeccable character” and one that is knowledgeable of the Liberia constitution and criminal law. In Liberia’s state and nation building endeavour, three professions have reigned supreme: politics, religion and law. The criteria insisting that the executive director is a trained Liberian lawyer limits the opportunity to recruit a more ideal chief of administration.

The second thing here is the inclusion of the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) and United Nations human rights office (OHCHR) to serve as panellists in this recruitment process. But to allow for greater local ownership, both ECOWAS and the UN have withdrawn from the process, leaving the Ministry of Justice in charge, along with members of the Independent Human Rights Commission of Liberia, Liberia National Bar Association, Liberia civil society and the Director of Cabinet. The absence of Liberian victims’ groups in the vetting process is notable. The withdrawal of the OHCHR and ECOWAS as critical oversight may bring full circle the elite conflict within the presidency and within civil society. In 2005 for instance, the UN and ECOWAS played a central role in the recruitment and selection of the TRC-2 commissioners.

September 20, 2024 marked the deadline for applications from those seeking to compete for the executive director position at the War and Economic Crimes Court Office. In the next few weeks, the Minister of Justice will be expected to submit a list of three competent Liberian lawyers to President Boakai for consideration. The extent to which the process will be perceived as inclusive depends on how it is managed, able to rise above potential conflicts of interest, and navigate the influences of partisan politics.

Aaron Weah is a civil society activist and leading expert on transitional justice in Liberia. He is a final year PhD researcher at the Transitional Justice Institute (TJI), Ulster University, and director of the Ducor Institute, a Liberia-based think tank on social and economic research. Weah is co-author of Impunity Under Attack: The Evolution and Imperatives of the Liberia Truth and Reconciliation Commission.