The name of current Chadian president Idriss Deby looks likely to come up often during the trial of his predecessor Hissène Habré, which opened in Senegal on Monday July 20.

The current strongman in N'Djamena has not been charged in the case, but he is often cited as a suspected accomplice of his former boss.

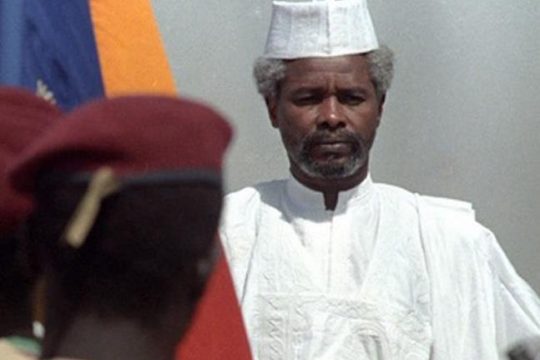

Former president Habré, whose trial was on Tuesday adjourned until September after the court assigned him three lawyers, is charged with crimes against humanity, war crimes and acts of torture committed under his regime.

Habré, now 72, has been in exile in Senegal for more than 20 years. He is has been detained since July 2013 in a Dakar prison.

He is being tried by the Extraordinary African Chambers (EAC), a special court created within the Senegalese justice system under an agreement between Dakar and the African Union. The court has a mandate to try serious violations of international humanitarian law committed in Chad from 1982 to 1990.

According to the prosecution, there is evidence of chains of command linking Habré to abuses committed by his feared political police, the Directorate of Documentation and Security (DDS), at whose hands human rights groups say some 40,000 people died.

But some lawyers in Dakar, such as Chairman of the Senegalese Bar Mbaye Guèye, think there cannot be justice for this bloody period of Chad’s history unless all the suspects, including the current Head of State, are made to answer in court.

Speaking in court on Monday, Mbaye Guèye criticized in scarcely veiled terms the fact that Idriss Deby has not been charged. Deby was at the time head of the Chadian army.

“For events over nearly ten years that left tens of thousands dead, you are only trying one man,” Guèye said during the opening ceremony of the Habré trial. “All the others charged have finally slipped through the net of justice owing to the will of one man who should himself appear here because he was in the forefront of the troops.”

Bringing all those responsible to justice

Another Senegalese lawyer went further in an interview with the press after the ceremony.

“The African Union has not given the African Chambers a mandate to judge Hissène Habré, it gave them a mandate to judge the facts, the crimes committed in Chad from 1982 to 1990. But these events implicate many people, some of whom are following this trial sitting comfortably in their armchairs in Chad,” said the lawyer, mentioning by name the current Chadian president Idriss Deby.

Amnesty International, which has long fought alongside the victims with other organizations like Human Rights Watch (HRW) and the International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH), expressed a similar concern. “Chad’s current President Idriss Déby has not been indicted by the Extraordinary African Chambers, but served as Chief of Staff of the army under Habré’s administration,” it said in a statement published earlier in the day. “Research undertaken by Amnesty International suggests that troops under his command may have committed mass killings in southern Chad in 1984.”

“The next step for the Chadian authorities is to ensure that no stone is left unturned when it comes to bringing those suspected of criminal responsibility for crimes under international law committed during Habré’s time in office to justice,” Amnesty’s West Africa researcher Gaëtan Mootoo said in the communiqué.

“The only way for Chad to break with its tragic past is to ensure all those responsible for the massive catalogue of human rights violations and crimes under international law face civilian courts,” says this human rights activist, who worked on Chad when Habré was President. “Anything less will send the message that these crimes are actually allowed.”

“Deby was himself a victim”

At a press conference on Wednesday in Dakar, Chad’s Communication Minister Hassan Sylla Bakari and Justice Minister Mahamat Issa Halikimi, who had come for the historic opening of the trial, defended their boss. After describing Habré as “the worst dictator humanity has ever known” and “a man who was capable of killing even his own parents”, the Communication Minister affirmed that Idriss Deby Itno “was never associated from near or far with the Directorate of Documentation and Security, the killing machine that is now in the dock”. He said that on the contrary, Deby was one of Habré’s victims. “He himself was a victim of that killing machine. He lost eleven members of his family,” the minister explained. His colleague the Justice Minister stressed that no complaint had been brought against Deby up to now. “Let us try not to jump to conclusions,” he said, visibly annoyed.

The two envoys from N'Djamena said that the Chadian government had no intention of putting the slightest pressure on the Extraordinary African Chambers, of which it is the biggest donor.